Europe’s economies are grappling with a multifaceted crisis marked by industrial stagnation, geopolitical instability, and the lingering effects of the energy crisis. Two critical factors are further impeding recovery: real wage stagnation and subdued household consumption.

Even though European labor markets have been relatively stable since 2020, real wages have failed to keep pace with inflation, eroding purchasing power and dampening consumer confidence in countries like Germany and the U.K. This, in turn, has stifled domestic demand, a key driver of economic growth. The result is a self-reinforcing cycle of weak consumption and sluggish business investment, exacerbating Europe’s broader economic malaise and stalling its post-pandemic recovery efforts.

German households refuse to consume amidst economic uncertainty

Germany’s economic performance since the COVID-19 pandemic has been, speaking generously, lackluster. GDP has held essentially flat since 2019 due to a combination of industrial weakness, poor export performance, weak domestic consumption, and a lack of government spending. And per-capita income is still lower than before the pandemic because of record-high levels of net migration.

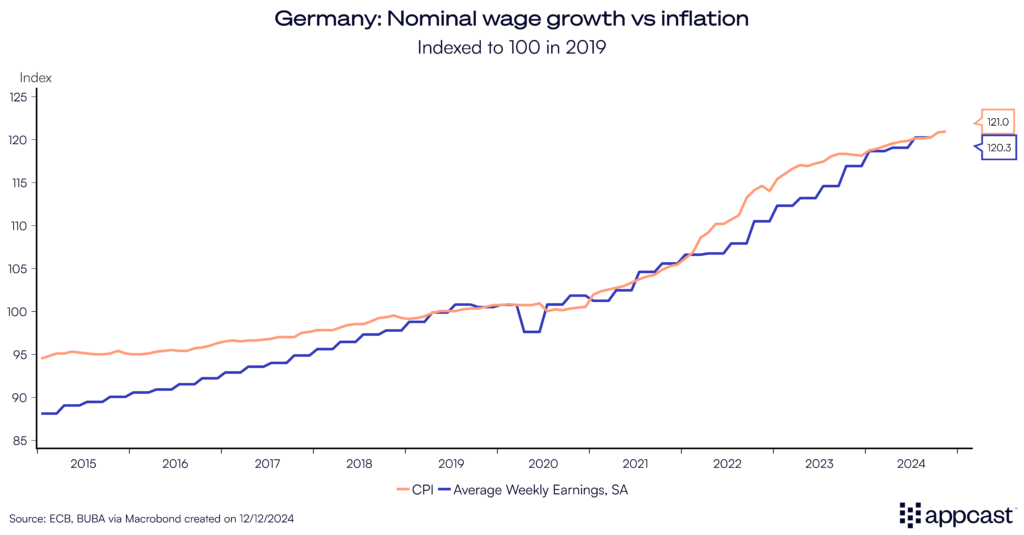

The pandemic and the energy price shock led to some significant inflation in recent years and nominal wages have barely kept up. Average weekly earnings are actually slightly lower than they were in 2019, meaning that the typical German worker has been dealing with complete wage stagnation for over four years.

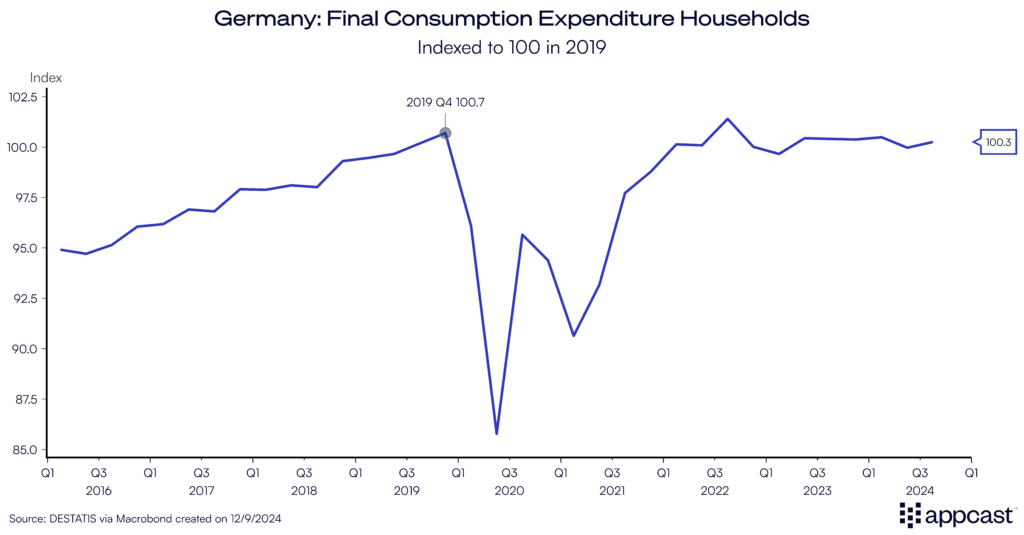

It is therefore no wonder that household consumption has been depressed for years. Expenditures of German households are, in inflation-adjusted terms, slightly lower than they were in late 2019!

Saving is not always a virtue

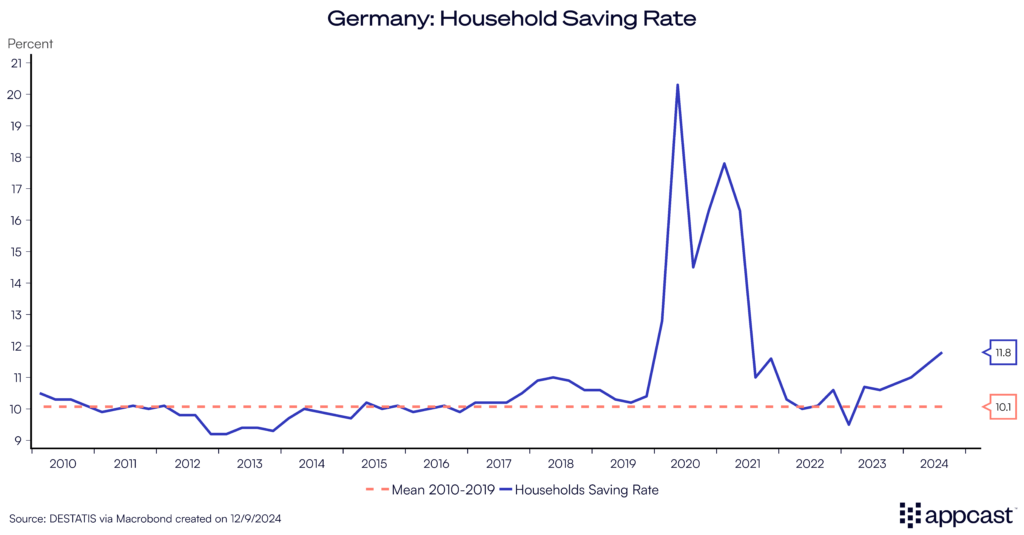

One element that has contributed to the general weakness of household expenditures is the large increase in the savings rate. While during the pandemic the massive surge in savings was very much “forced” – consumers were unable to spend money as the economy was for weeks or months at a time in intermittent lockdown throughout 2020 and 2021 – households are now voluntarily saving way more than before the pandemic.

While the saving ratio averaged 10% between 2010 and 2019, it has steadily crept up to almost 12% over the last two years. Household gross disposable income in Germany is just exceeding 2.5 trillion euros. An increase in the savings rate of two percentage points means that some 50 billion euros in private consumption, about 1.5% of GDP, are missing from the economy.

Why are German households suddenly saving so much and spending so little?

Economic uncertainty has been extremely high ever since the pandemic, given the subsequent energy price shocks and the war in Ukraine.

German manufacturing is in a severe crisis and the news is full of concerning stories of large German employers shedding jobs. GDP in Western German states that harbor the classical manufacturing belt is now contracting (Baden Wurttemberg, Bayern, Lower Saxony).

The automotive sector in particular, responsible for a couple of million jobs, is in severe crisis as German car manufacturers are struggling to compete with China. On top of planned layoffs, companies like Volkswagen are also negotiating wage cuts to remain competitive.

It therefore shouldn’t come as a surprise that many German employees are tightening their belts. The mood among workers is increasingly sour and the depressed sentiment might even contribute to the increase in sick absence rates that German companies have been facing.

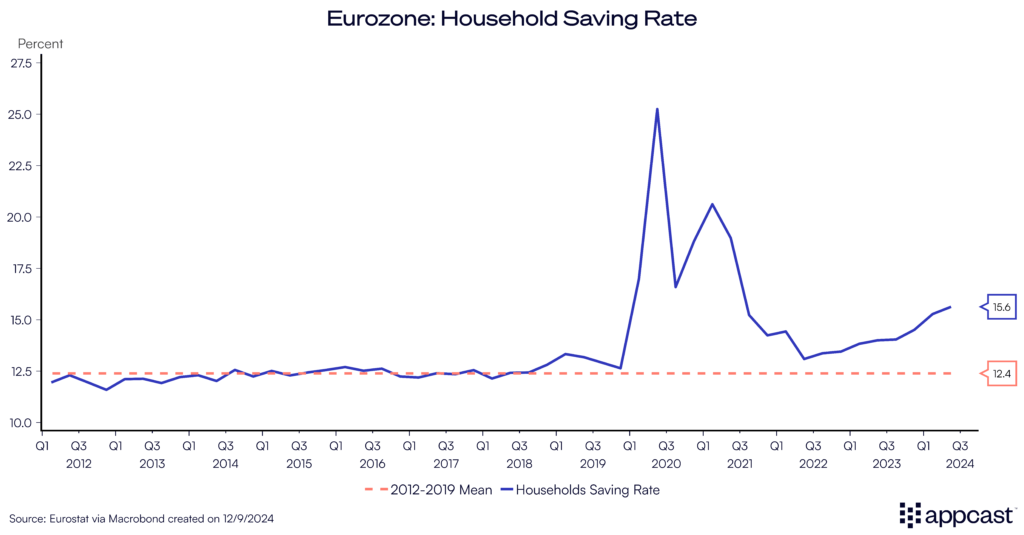

The saving rate is up across Europe

It is not just German households who are saving more. For the Eurozone as a whole, saving has increased from about 12.5% before the pandemic to a recent high of over 15.5% this year. Economic uncertainty is weighing on consumer spending and as European citizens are tightening their belts. An increase in households’ savings preferences leads to lower consumption, which in turn depresses the demand for goods and services in the economy, and by consequence, is a negative for jobs and the hiring outlook.

British households: Buying less and saving more

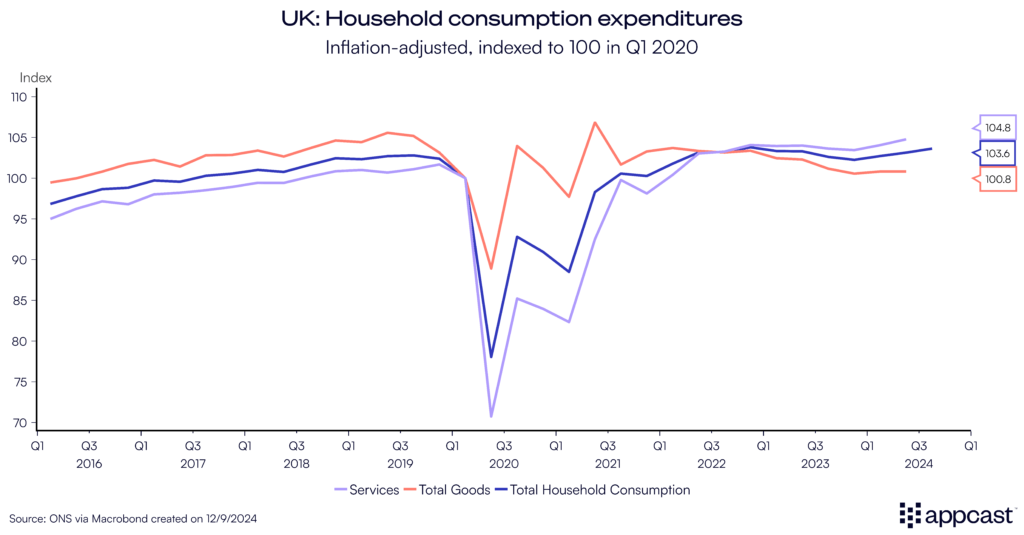

Looking across to the other side of the Channel, one can see that U.K. households are behaving in a very similar way to their continental European counterparts, saving way more than before the pandemic. Household consumption in inflation-adjusted terms is up by less than 4% since 2020. This better performance is due to slightly higher growth than in Germany, but overall, still a mediocre increase compared to the U.S. Spending on goods in the U.K. has been flat since 2019 while spending on services has gone up by close to 5%, leaving overall consumption slightly higher.

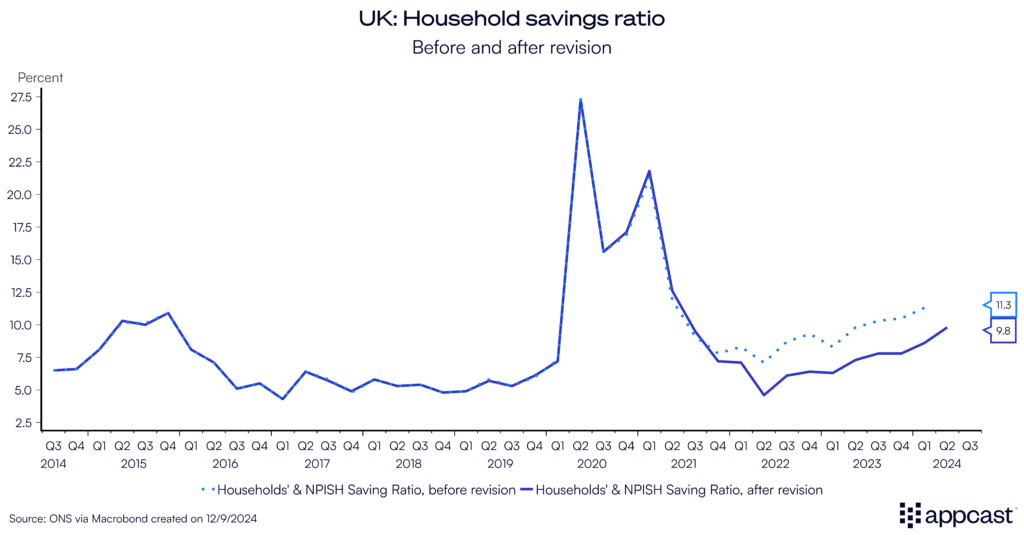

For British households, the saving rate averaged some 6.5% between 2014 and 2019 (in the immediate years before the pandemic it was closer to 5%). Since 2022, the saving rate has increased by several percentage points, now at 10%.

Total household consumption in the U.K. exceeds 1.6 trillion pounds per year. A three-percentage point increase in the saving rate depresses annual consumption by over 50 billion pounds, a substantial negative economic shock.

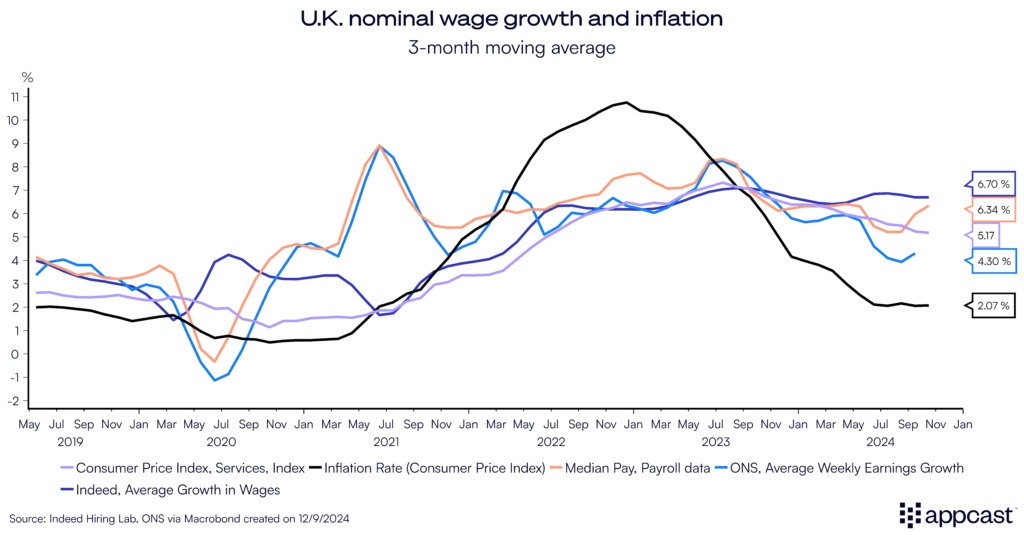

Strong real wage growth boosting consumer confidence

Unlike Germany, real wages are growing at a healthy rate in the U.K. again. While inflation has fallen rapidly since 2023 and is now basically back at target (2%), nominal wage growth has remained incredibly sticky. In fact, salaries continue to grow at a rate of over 6%, depending on the precise measure you use.

Real wage growth is currently growing at a rate of approximately 4%, much higher than anything that workers have seen in many years, if not decades.

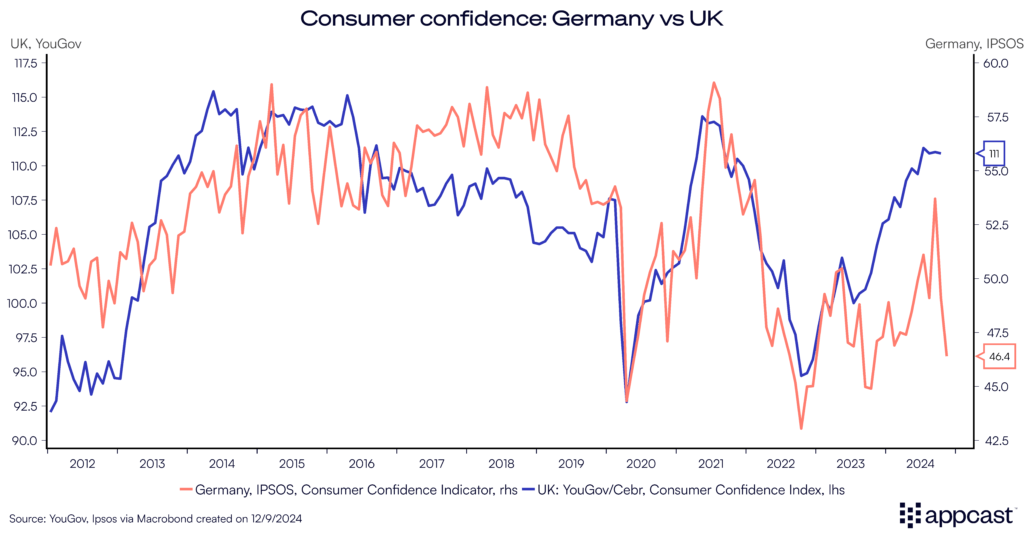

It is thus not surprising that consumer confidence in the U.K. has finally improved dramatically since 2023 as inflation-adjusted pay has increased at the same time.

Compare that to Germany where consumer confidence remains historically depressed, unsurprisingly, as both the employment outlook and prospective wage gains are much weaker.

What does that mean for the labor market?

It is plausible that heightened economic uncertainty since the pandemic has led European households to save significantly more than before the pandemic because of increased risk-aversion. Households want to build up their cash buffers in case of emergencies. While this is not necessarily a bad thing in the long run, it temporarily depresses consumer spending and thereby reduces economic growth. The decline in household spending on goods and services, in turn, is a negative for the labor market since it reduces the demand for workers across various industries, including retail and hospitality.

But eventually, European households will have filled their cash coffers sufficiently. The positive momentum in consumer sentiment in the U.K. will eventually translate into higher household spending again as real wages have performed well for more than a year.

What does that mean for recruiters?

Saving is not always a virtue. The American economy has outperformed Europe by a substantial margin in recent years. While a lot of that is due to stronger productivity growth, lower regulatory burdens, and cheap energy prices, American consumers are also spending their incomes. Strong consumption growth is giving the American economy a further boost.

In Europe, on the other hand, households have been increasingly cautious and outright pessimistic. The saving rate has increased in recent years to a record high (disregarding the lockdown periods). The lack of domestic consumption is another headwind that the European economy is now facing, and it has implications for the labor market, too.

Low demand for goods and services translates into lower employment in industries like retail, hospitality and accommodation, all of which are dependent on consumer spending.

There is quite a lot of evidence that European countries have been hoarding labor during the recent economic stagnation, meaning that they have refrained from layoffs even as the economy has soured. If consumer spending remains depressed, some job cuts will eventually become necessary. If, on the other hand, saving rates finally dip down again, hiring in the aforementioned industries is likely to pick up. One can but hope that European consumers turn more optimistic and start to splurge like Americans for all our sakes!