The UK’s stability in international GDP rankings

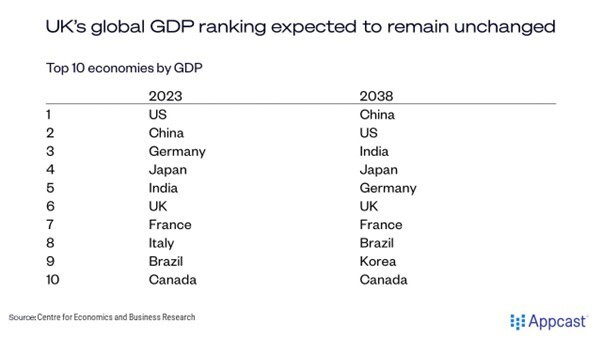

Bloomberg recently reported some good news that should cheer up readers in the U.K. While most advanced economies are expected to decline in the ranks when it comes to international GDP rankings, the U.K.’s position is expected to remain stable.

As large emerging markets like China, India, and Indonesia have been recording high growth rates for decades and their respective populations far outweigh those of Canada and Italy, emerging economies will surpass most developed economies in size.

Furthermore, rich countries like Italy, Germany, and Japan also suffer from a rapidly shrinking population and workforce.

The U.K., on the other hand, is expected to remain the sixth-largest economy in the world until about 2040, according to projections from the Center for Economic and Business Research.

The country’s productivity problem

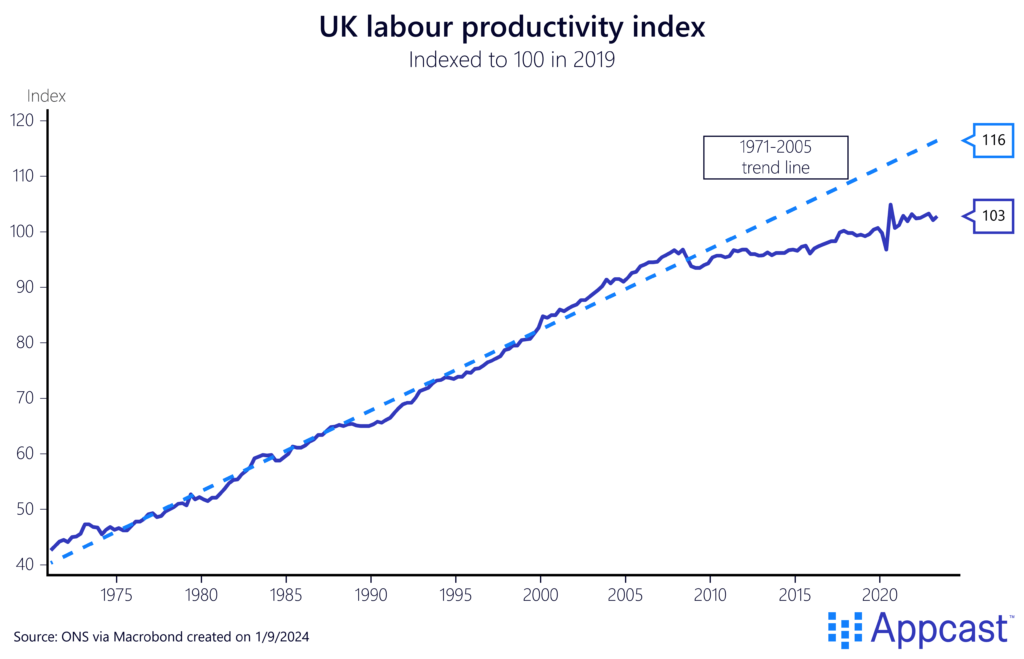

While this is certainly good news, the bad news is that the U.K.’s growth over the last decade is the result of population growth for the most part, while incomes have stagnated. The chart below shows to what extent labor productivity has stalled in the aftermath of the financial crisis.

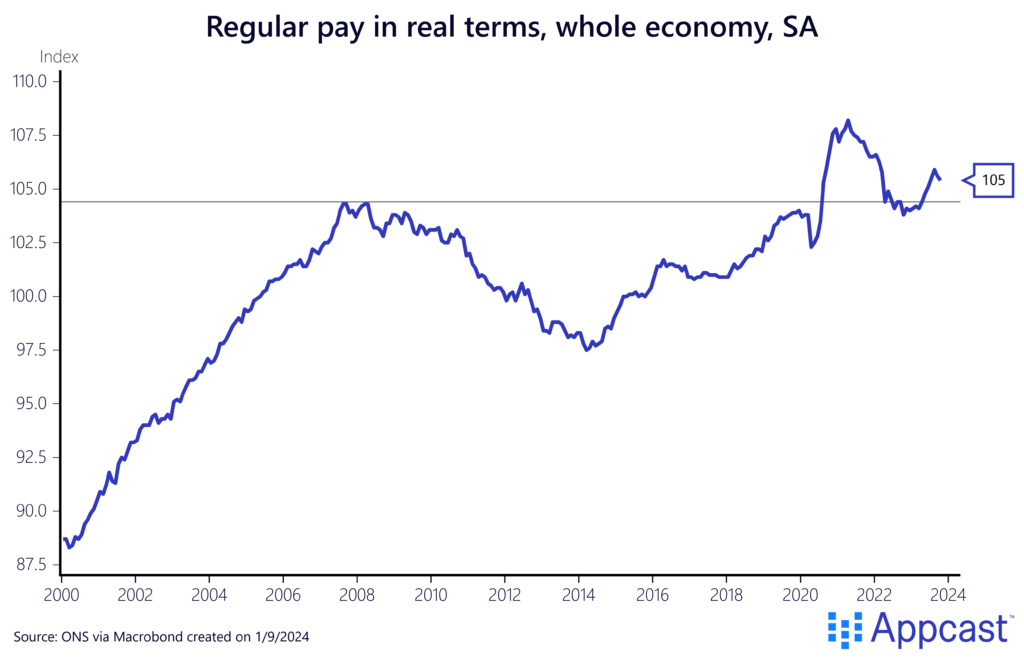

Under previous decades’ trends, labor productivity would be more than 10% higher. That lack of productivity growth has been extremely costly for workers. Average real wages in the U.K. are not much higher than they were in 2006, meaning that we are closing in on the second decade of wage stagnation.

With productivity and wages stagnating, GDP per capita is not significantly higher than it was in early 2007, making this the longest period of economic stagnation since the start of the Industrial Revolution. In this piece, we will not dig deeper into the causes of the UK’s underperformance as they are multi-causal and require several research pieces on their own – you can consult some of my other writings. Suffice it to say that the U.K. has been underperforming because of its lack of investment in public infrastructure in recent decades. A completely dysfunctional housing market with house prices surging far too high relative to incomes, the underutilization of skilled workers outside of London, and the lack of productivity in the UK’s second-tier cities also play a prominent role.

Population growth explains the UK’s growing economy

So, if incomes in the U.K. have been stagnating for so long, how come the U.K. economy is still growing?

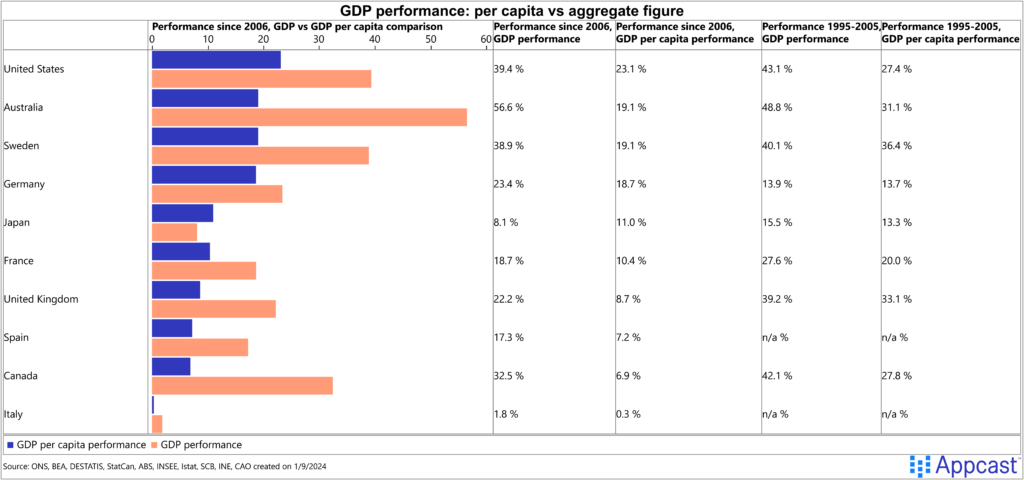

The answer, of course, is that most of the increase is due to population growth. When looking at the aggregate figure, UK economic performance has not been that terrible since 2006 compared to other large, advanced economies: some 22% growth. However, GDP per capita has only increased by a meagre 7% during those 18 years – less than 4% per decade – thus increasing at an almost glacial pace.

Compare that to the high growth era of the tech boom. During the decade from 1995 to 2005, per capita GDP was growing at a rate of close to 28%.

As the U.K. economy was growing so strongly in the 1990s and early 2000s, population growth also exploded. The U.K. attracted a large inflow of migrants, especially from Eastern Europe, as those economies joined the European Union in 2004.

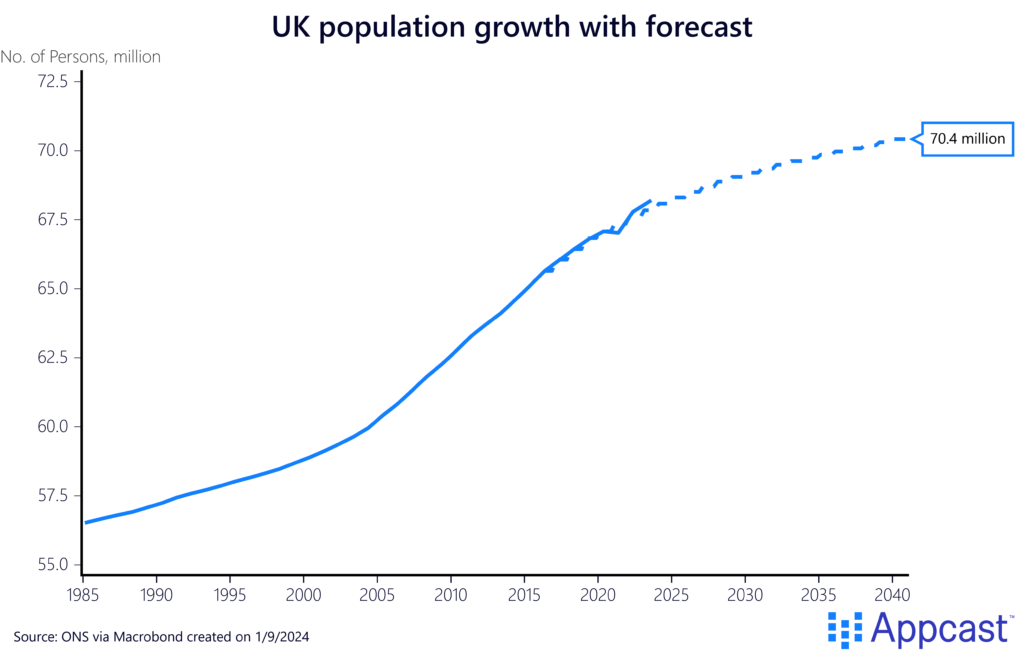

The U.K.’s population grew from about 58 million at the end of the 1990s to just under 68 million today. While population growth and income growth went hand in hand during the 1990 tech boom, income growth has been stagnant since the financial crisis.

Forecasters expect the U.K.’s population to increase above 70 million in the decade to come. However, there is a large amount of uncertainty around this estimate, as it currently looks like population growth will exceed the forecast.

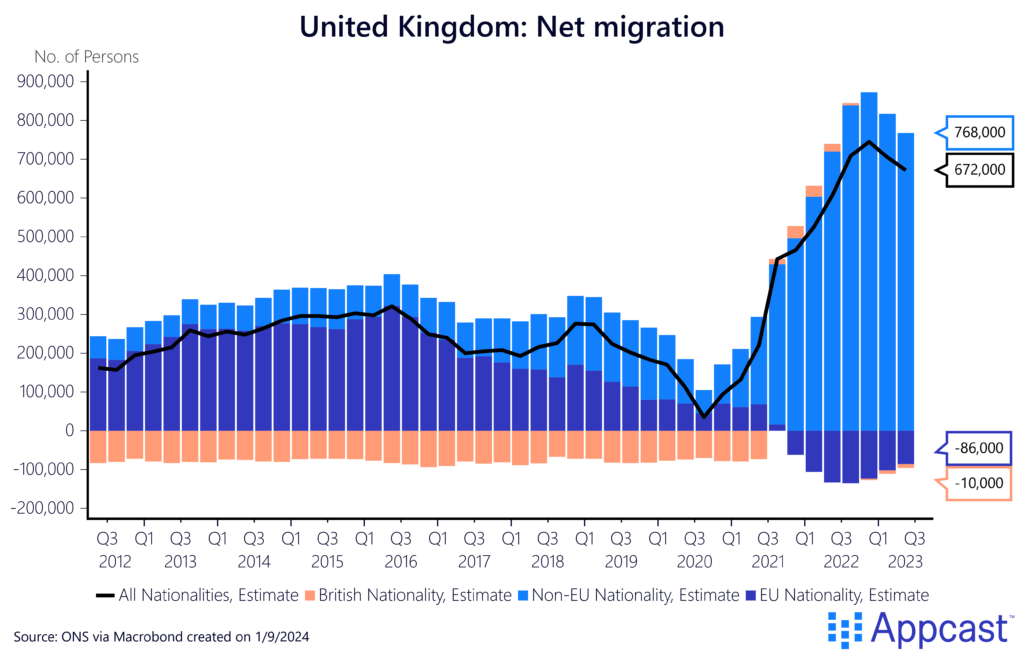

While the domestic birth rate is a very slow-moving variable and easy to anticipate, migrations inflows are much more uncertain.

Despite Brexit, the U.K. is currently receiving much more migrants than before the pandemic. Over the last two years, more than 1.2 million people have migrated to the U.K. on net, which is currently leading to a populist backlash at home. In an election year, the government is now desperately trying to restrict inflows even though the additional workforce will be needed in the future.

International migration decisions are caused by many push and pull factors. Push factors include wars, famines, and other crises together with lack of economic opportunities in the origin nations. Pull factors include economic opportunities in the receiving country together with the current migration regime in the destination high-income economies.

Conclusion

The U.K.’s economic pie has been growing and will continue to grow. However, since the financial crisis, this is mostly a result of population growth instead of income gains – individual workers’ slices of the pie haven’t grown much. While the fact that the U.K. workforce is expanding faster than in most other advanced economies is good news, income stagnation is certainly contributing to the current populist backlash. The U.K. government needs to pursue a much more aggressive growth agenda that focuses on more than just tax cuts. The country’s housing market is broken, public infrastructure has been far too low for years, many graduate workers end up in non-graduate jobs outside of London. The country’s problems are many and it risks falling further behind the likes of Germany and France if the productivity problem is not addressed.