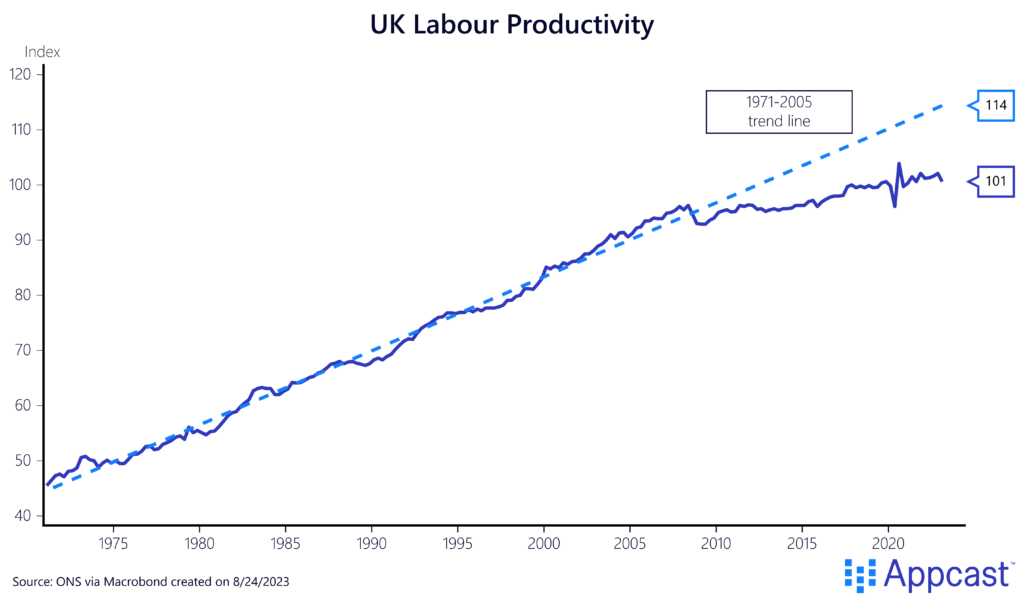

The U.K.’s productivity problem

The U.K. economy has had a severe productivity growth problem since the Great Recession. The chart below shows that if productivity had grown at the previous trend line, it would currently be about 13% higher. That would also mean that the aggregate wage income would be some 13% higher than it is right now.

For context, the median salary for a full-time worker is about £33,000 in the U.K. right now but would have been more than £4,000 higher if the economy had grown in line with the old trend.

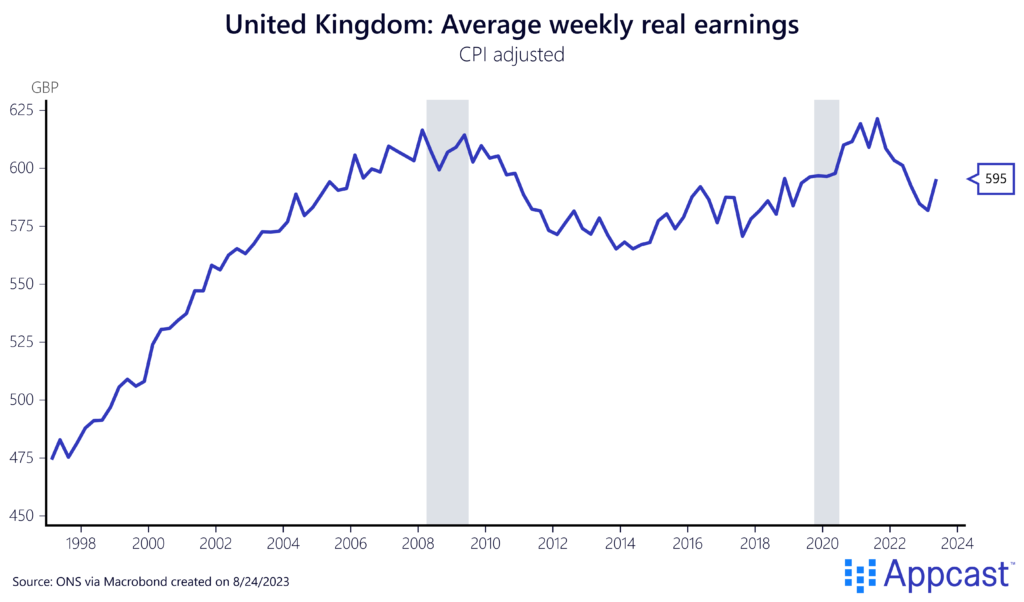

Wealth increases even as wages stagnate

As expected, the productivity stagnation has brought about a prolonged period of real wage erosion in the U.K. Average weekly real earnings are not higher than they were in the early 2000s. Barring countries like Greece, few other advanced economies have seen such poor economic performance and stagnation of living standards for the average worker. In fact, this is the first time since the Industrial Revolution in the mid-19th century that U.K. average weekly earnings have stagnated for about two decades.

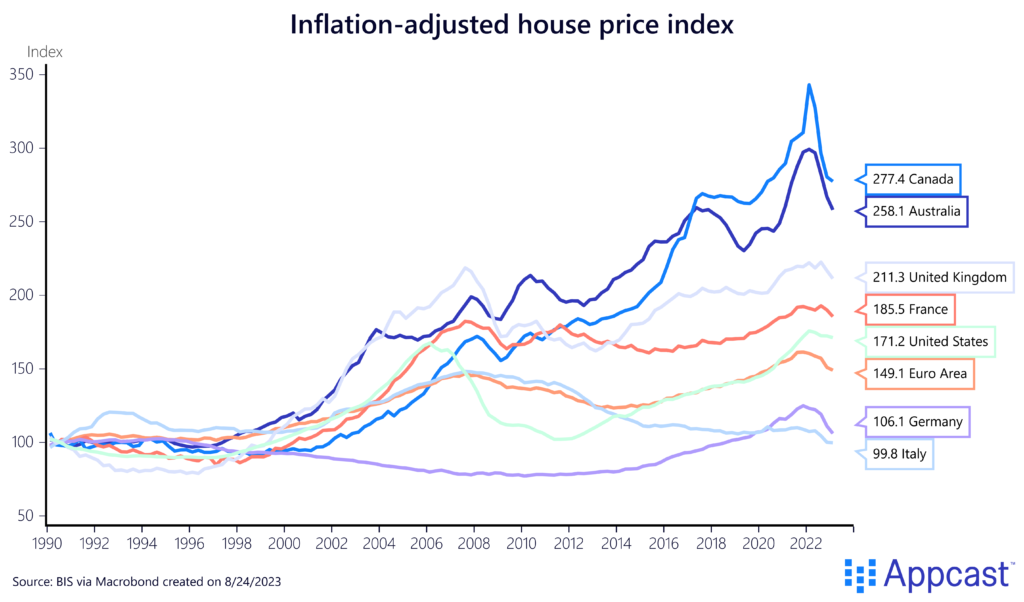

But even as incomes have gone sideways, wealth has increased, and the main driver of this has been the housing market. Inflation-adjusted house prices in the U.K. have increased by much more than most other advanced economies.

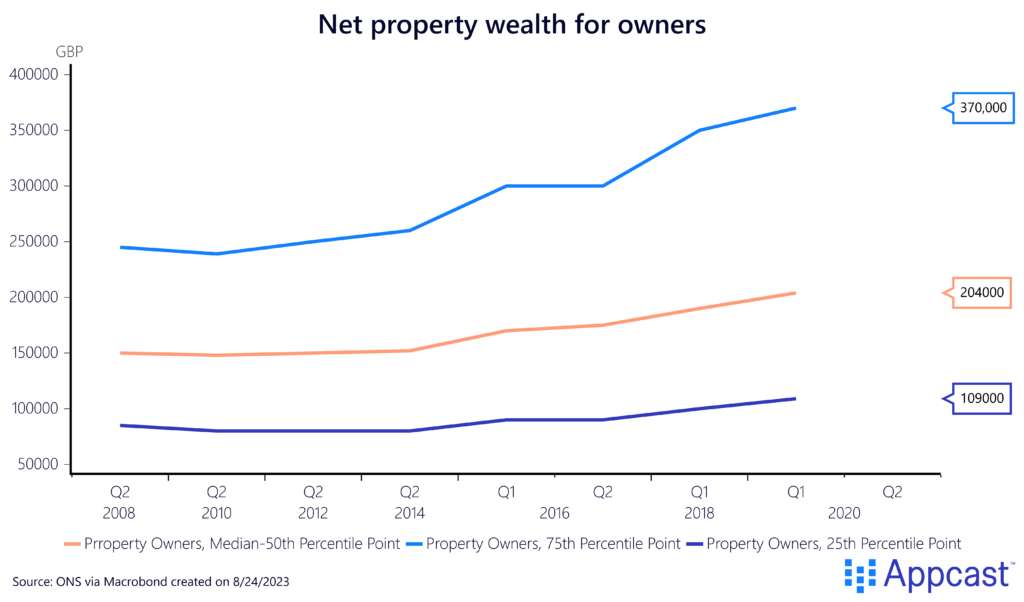

Thanks to the rapid house price appreciation, homeowners have seen their wealth increase substantially in the U.K. economy even as incomes have stagnated.

The median household net property wealth stood at about £112,000 in early 2020 in the U.K. That number is substantially dragged down by all households who do not own a home and therefore have a net property wealth of zero. As one can see, among all homeowners, the median net property wealth was almost twice as high at £204,000.

The median homeowner also saw their net wealth increase by more than a third, or £50,000, between 2008 and 2020, whereas the top 25th percentile saw their net wealth go up by about £120,000 during that period.

House prices are outpacing earnings

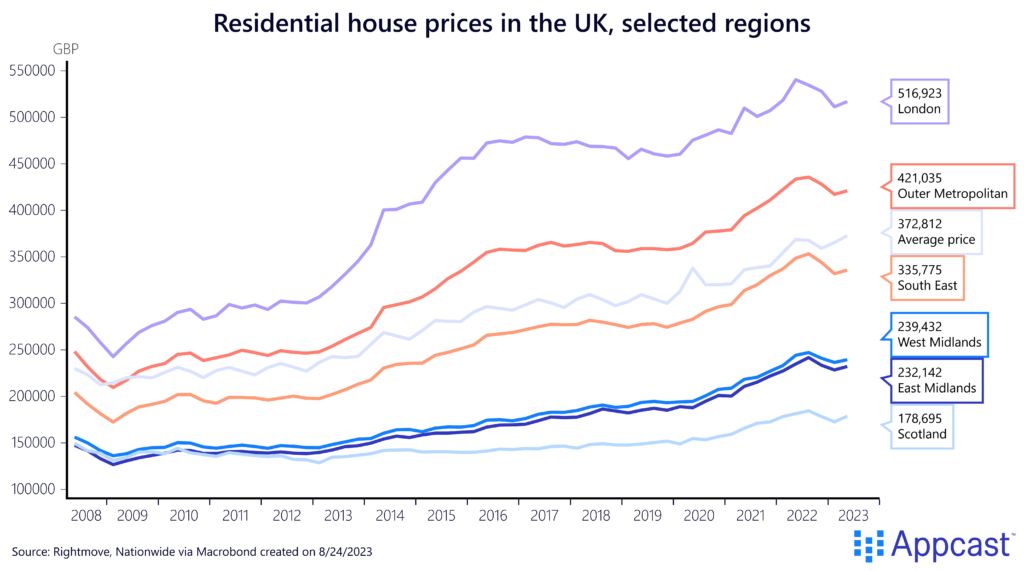

As everybody in the U.K. is aware, London is the epicenter of this housing crisis. House prices in the London area are about 50% higher than the U.K. average. They increased from under £300,000 in 2008 to more than £500,000 during the pandemic. Even the average house price in the U.K. increased from less than £250,000 to more than £360,000 right now.

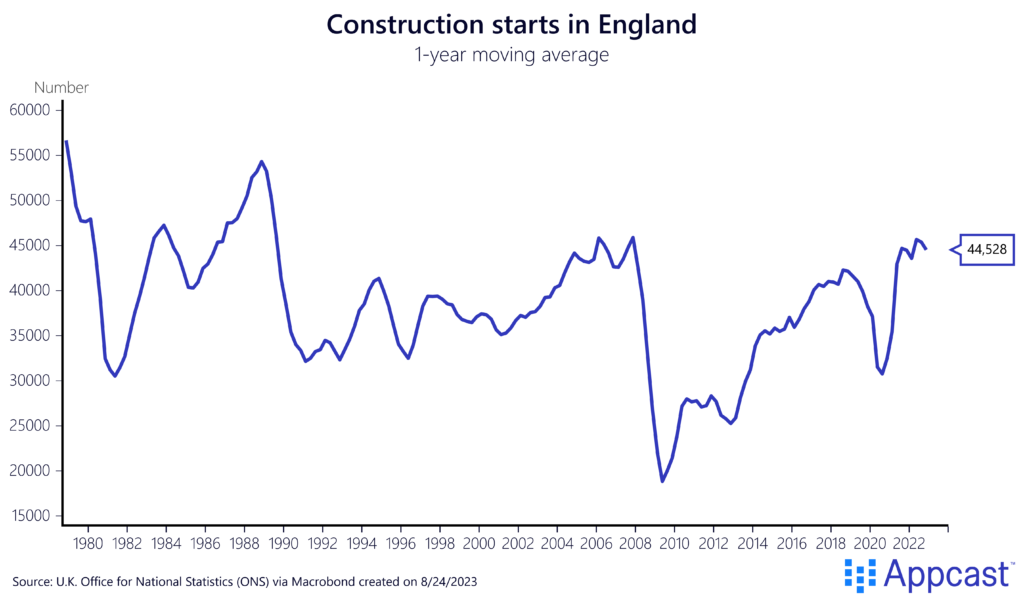

The dysfunctional U.K. planning system is the main culprit for these rising prices in London and beyond. Construction starts have been depressed for decades – the U.K. has been building much less housing than in the 1980s even as the population has grown – and some estimates suggest that there are close to four million missing housing units in the entire country.

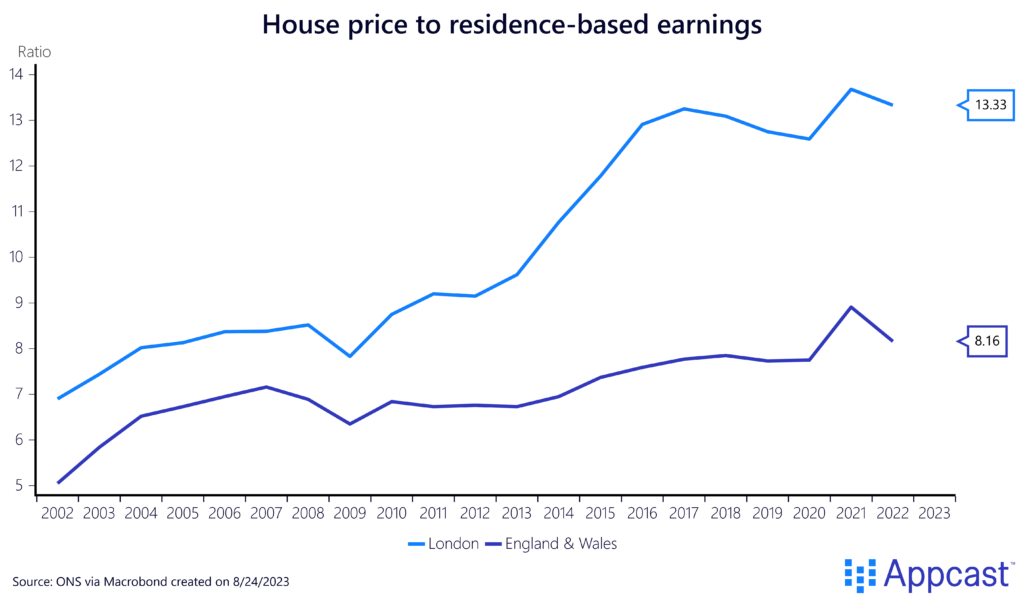

The lack of housing supply explains why prices have outrun salaries in recent decades. Office of National Statistics (ONS) data shows that the house-price-to-earnings ratio has increased from about five to more than eight for the U.K. over the last 20 years. For London, this ratio has almost doubled from seven in 2002 to about thirteen right now. The average London house price is now 13 times greater than earnings, which explains why most Londoners now need a full decade to save up for a deposit, unless they get help from the “bank of mum and dad”. To no one’s surprise, recent research from the Bank of England shows how people that receive monetary support from their parents here in the U.K. can afford a home much earlier in life.

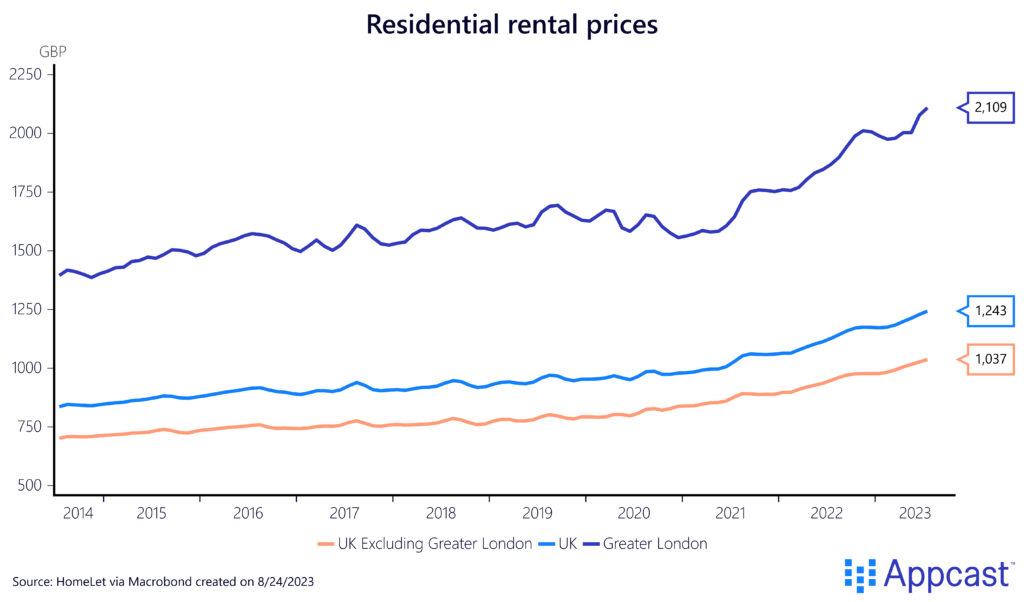

This insane increase in house prices has also spurred a large increase in rental prices over the last decade. Rents in London increased from about £1,400 in 2014 to £2,100 this year, thus far outpacing earnings. For comparison, the London average salary is about £57,000, which means about £3300 in net salary (after deducting about £2000 in council tax). According to that calculation, the average single earner would have to spend some 60% of their net income on rent. Even with most London households being dual earners or flat sharers, many London renters are spending some 30 to 40% of their net income on rent alone.

The dysfunctional housing market is hurting the labor market and economy

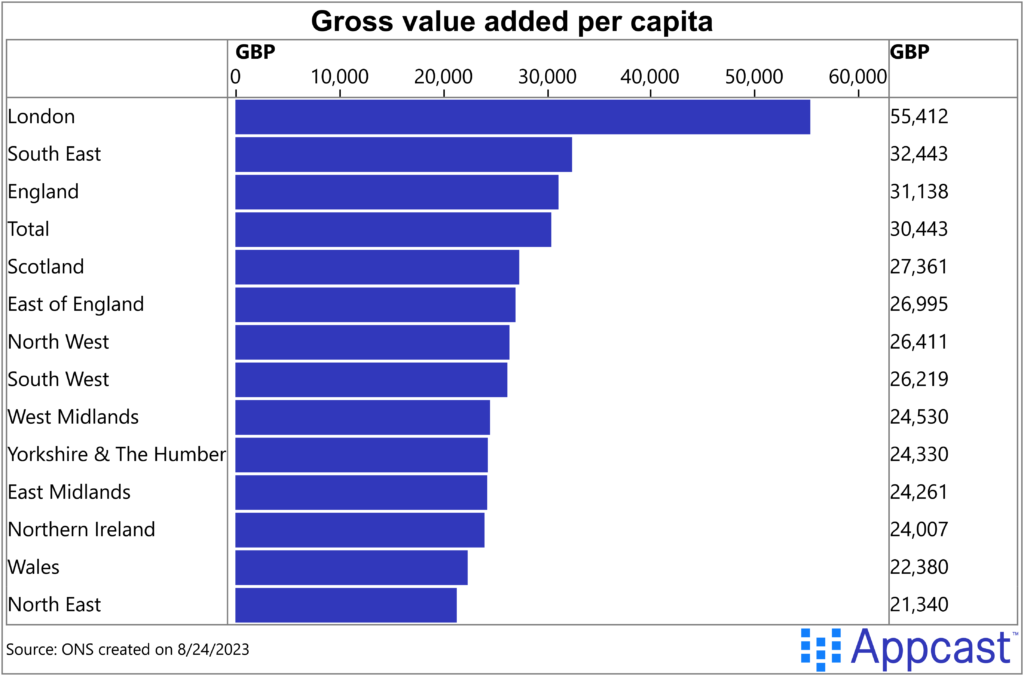

The macroeconomic effects of the dysfunctional housing market in the U.K. are hard to pin down precisely but should not be underestimated. The U.K. is one of the advanced economies with the largest regional inequalities. Gross value added per person in London is slightly over £50,000 and thus about 2.5 times higher than the poorest region, the Northeast (£21,000).

London and the Southeast have, by far, the most high-paying jobs but prohibitive housing costs and the lack of housing supply prevent workers from taking advantage of these opportunities. For many workers, it simply might not make sense to move to London anymore for a 20% pay bump if their rent increases by twice as much or more while having less space. The lack of supply is thus preventing more workers from moving to London.

But the U.K. economy is too London-centric anyways. For instance, Oxford and Cambridge Universities top international rankings. While these cities have a research cluster, many companies shy away from “setting up camp” there for the simple reason that both cities are quite small and have a limited, local, skilled labor pool – Oxford and Cambridge are close to 150,000 inhabitants each (their respective metropolitan areas are slightly larger).

Doubling the size of those cities would lure more companies to set up shop there, attract more business investment, and retain more talent locally. Alas, local opposition will ensure that any plans to sizably increase those cities will not come to fruition. This anti-growth attitude is one of the main reasons why the U.K. has underperformed in recent decades. Absent an embrace of growth, the U.K. economy will continue to do poorly.

Conclusion

House prices have far outpaced earnings in the U.K in recent decades. The dysfunctional housing market is one of the main reasons why the U.K. economy has a growth problem: It prevents workers from moving to high-productivity cities. Better housing affordability in the major U.K. cities can only be achieved via an increase in supply. This would require an overhaul of the British planning system, which currently prevents the country from achieving its housing targets and is a big obstacle to economic growth.