GDP shortfalls for years to come?

We recently wrote several blog posts about the U.K.’s short-run economic outlook. The Bank of England (BoE) was still extremely pessimistic at the end of last year, forecasting a deep and prolonged recession. This never made too much sense to us and, indeed, their near-term outlook recently improved.

Both the Office for Budget Responsibility and the BoE are now forecasting the U.K.’s unemployment rate to peak at 5% even as the country is falling into a recession this year. While the expectations are now set for a shallow downturn, households continue to suffer during the cost-of-living crisis and inflation outpacing wage gains.

Somewhat more worrying than the near-term outlook is the BoE’s pessimistic assessment of future productivity growth and the country’s labor supply. The U.K. already experienced more than a decade of abysmal productivity growth after the financial crisis. The consensus now is that the self-imposed austerity measures back then led to substantially lower growth in the years following the Great Recession.

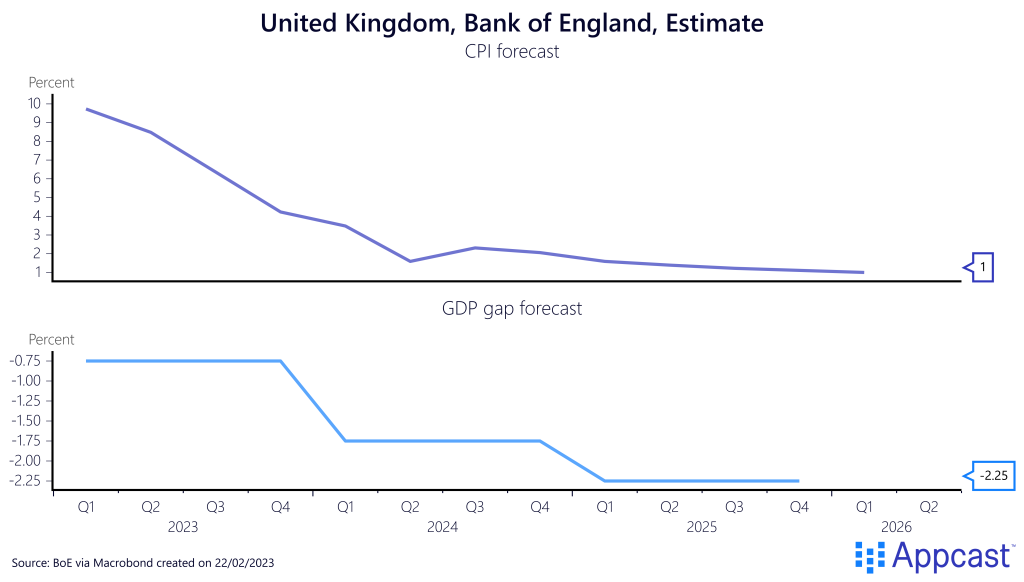

And according to the BoE, the future is even more grim. The new projections are assuming that there will be slightly negative growth until early 2024, followed by an extremely mediocre recovery. From Q1 2025 to Q1 2026, the BoE is projecting less than 1% growth while inflation will stay below target for a couple of years.

However, just as last year’s short-run outlook was too pessimistic, something about these long-run projections is off as well. Forecasting an inflation undershoot for two years in a row along with a negative GDP gap (relative to “potential”) makes little sense to me. Both metrics would imply that the economy is operating well below capacity and that more stimulus is needed to bring it back to trend.

Since it is the Central Bank’s job to bring the economy back to its potential when demand is lacking, this forecast seems to suggest that the BoE is willingly accepting or even engineering a sluggish recovery with an inflation undershoot in the next couple of years. While the 2022 inflationary surge has been horrifying, it would make sense to treat this mistake as “bygones be bygones”. After all, that has been the modus operandi of most central banks for years after the financial crisis, when they undershot the inflation target for several years and never made up for it either.

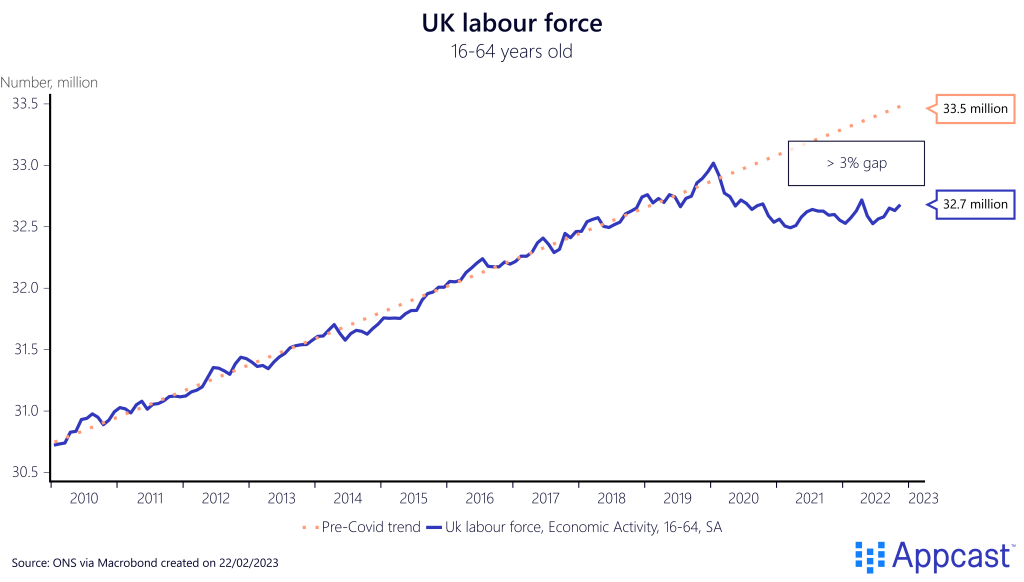

The U.K.’s missing workers

But it is not just the demand side that gives reason to worry. The BoE is also increasingly pessimistic about future productivity growth in the years to come. The main reason is that the U.K. is more than 3% lower compared to its pre-COVID trend as I argued in this article.

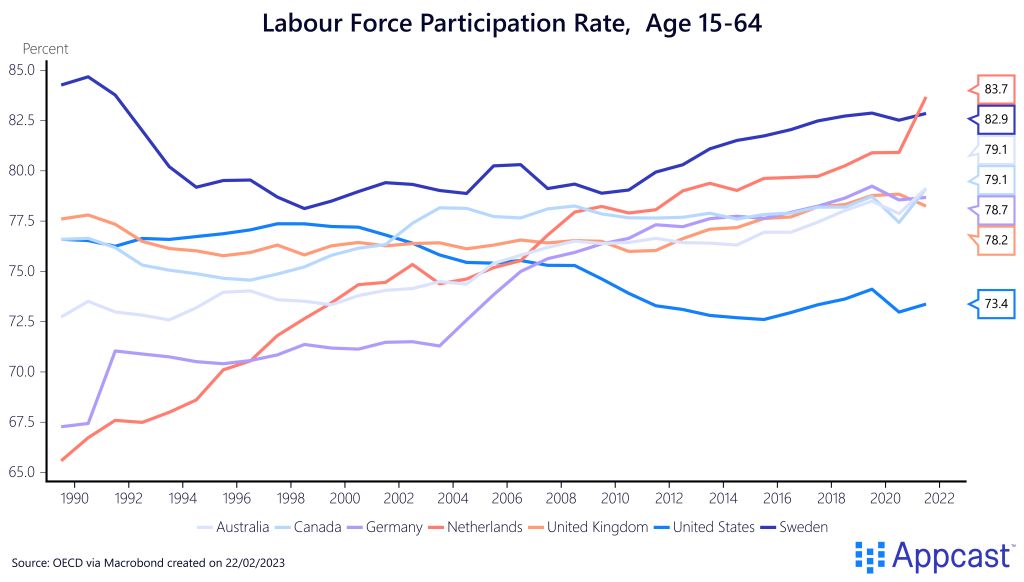

More than 330,000 workers are missing in the service sector because of Brexit. Even more worrying, the number of inactive workers in the U.K. is very high compared to other advanced economies. The participation rate in the U.K. has completely stagnated while other countries have seen a recent uptick.

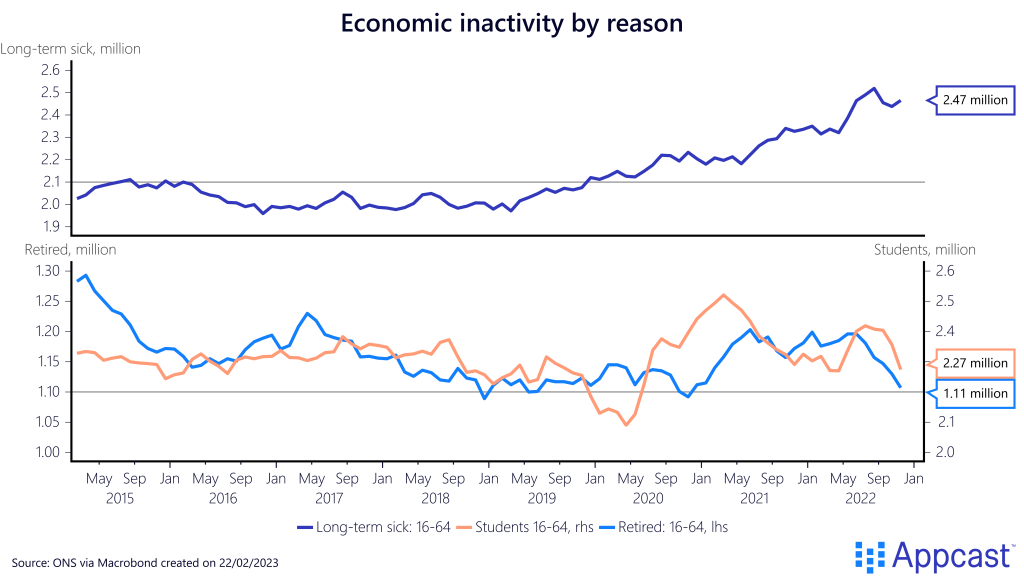

Of particular concern are the reasons for inactivity in the U.K. The following chart shows that more than 500,000 people left the workforce due to long-term health reasons. These are the long-term effects of the coronavirus pandemic. Many people who caught the virus are suffering from long-COVID. Moreover, the overburdened health care system in the U.K. during the pandemic also left many suffering from other long-term health issues without adequate care, thus aggravating the problem.

The number of retirees also increased throughout 2022 but has mostly reversed since then as the cost-of-living crisis is pulling them back into the workforce.

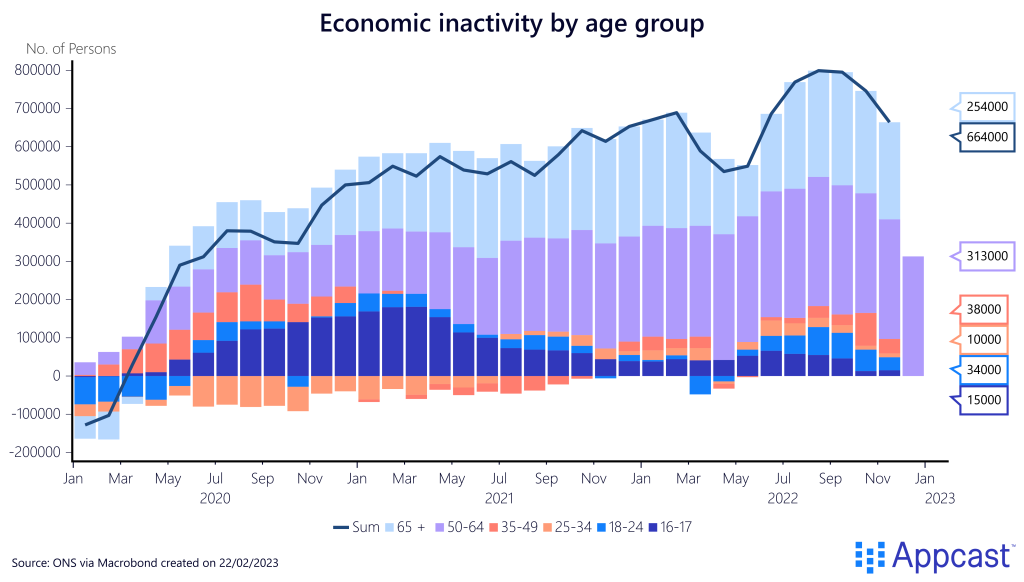

However, looking at the changes by age group, one can see that it is mostly people aged between 50 and 64 and those aged above 65 that have seen the largest increase in economic inactivity since early 2020 – more than 300,000 and 250,000 people, respectively.

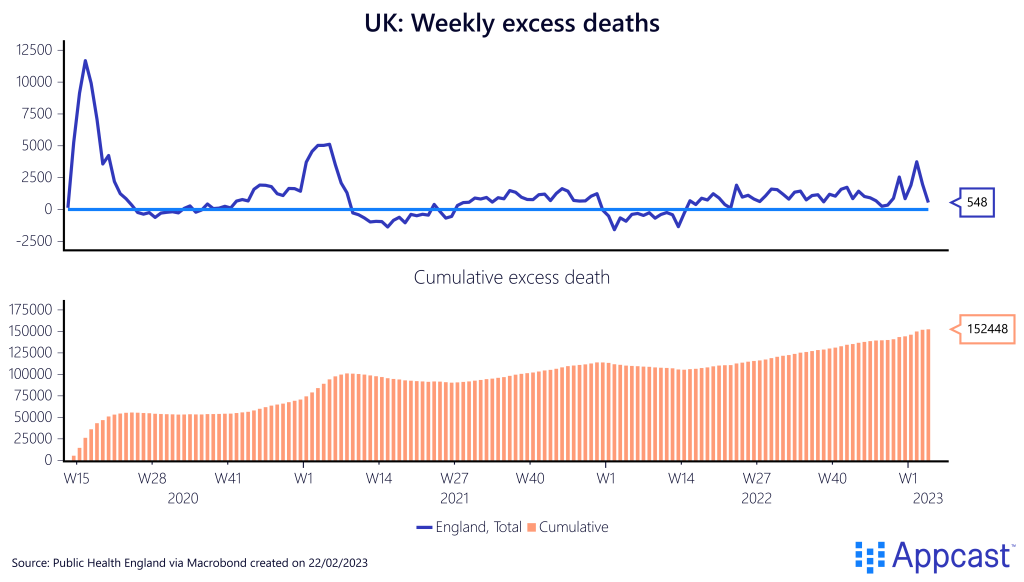

These older age groups have been more affected by the dysfunctional, overburdened U.K. healthcare system. Weekly excess deaths are still rising and have been averaging about 1,000 persons since the middle of last year.

But some of them are also enjoying early retirement because they have seen their houses appreciate massively in value during the pandemic.

Fixing the NHS and bringing the long-term sick back into the workforce should be on top of the list for policy makers.

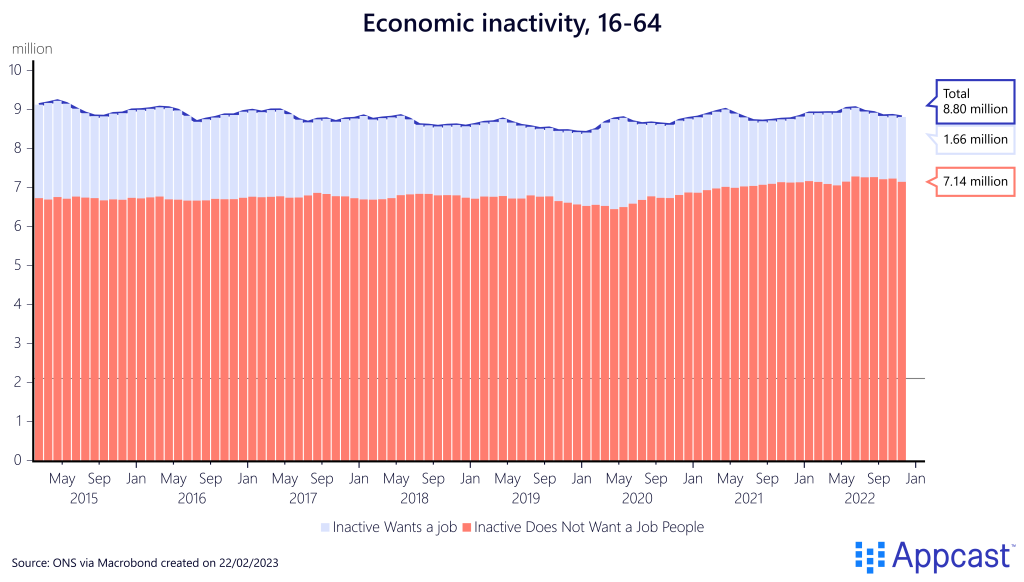

In general, there are close to 9 million people between 16 to 64 years old who are inactive in the U.K. and more than 1.6 million of those would like work.

Conclusion

The U.K. has a very large inactive population, especially in the older age groups. Some of them have retired early as they saw their house prices appreciate. More than half a million people dropped out of the workforce due to long-term health issues. Since the U.K. economic performance has not been that stellar in recent years, boosting long-term growth should be of high priority and decreasing the very high share of inactivity among the population is key. One could start with fixing the NHS, and therefore helping to reduce the number of people with long-term sickness.