Rising inequality no more!

The media is full of stories about rising inequality and how things are getting out of hand, but doom and gloom generally sells better. It is true that wealth inequality has risen substantially in recent decades, mostly a result of rapidly rising real estate and stock prices. Therefore, most people assume that income inequality has risen as well. However, the U.K. has actually experienced a quite remarkable wage compression over the last decade, with incomes at the bottom growing more rapidly than incomes at the top.

We will see that declining wage inequality was the result of policy. More specifically, the U.K. has progressively increased the minimum wage to very high levels, which caused incomes at the bottom to rise. Meanwhile, more than a decade of mediocre economic and productivity growth has caused wage stagnation at the top.

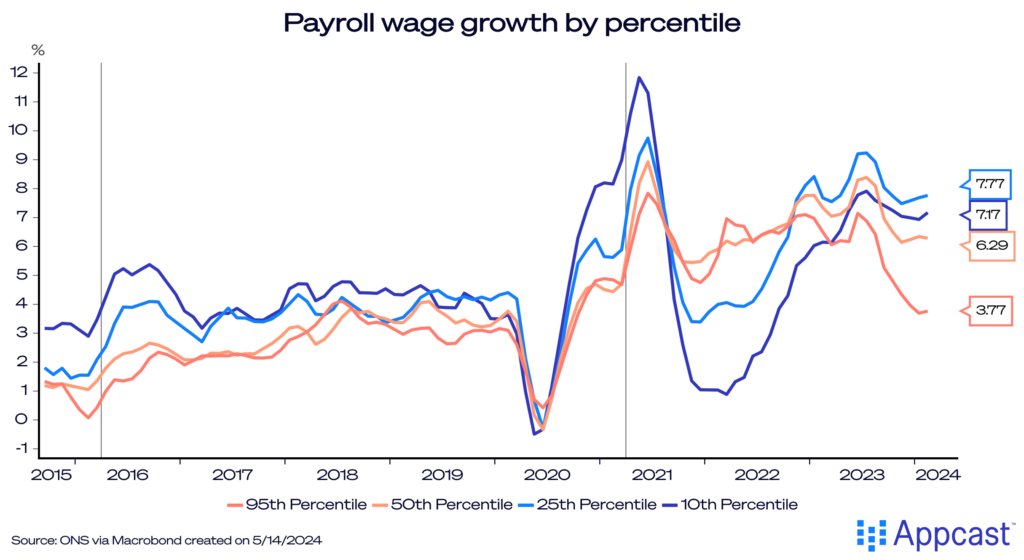

Data from the U.K. tax collection agency (HMRC), shows that salaries within the 10th and 25th percentile have grown significantly faster than salaries at the median or the top (the 95th percentile).

From 2015 to 2017, low incomes grew at roughly twice the rate than incomes at the top. We can see that the same thing happened in the beginning of the pandemic in 2021 and now again: Lower incomes are currently growing at rate of 7% or above while the 95th percentile is growing at a rate of less than 4%.

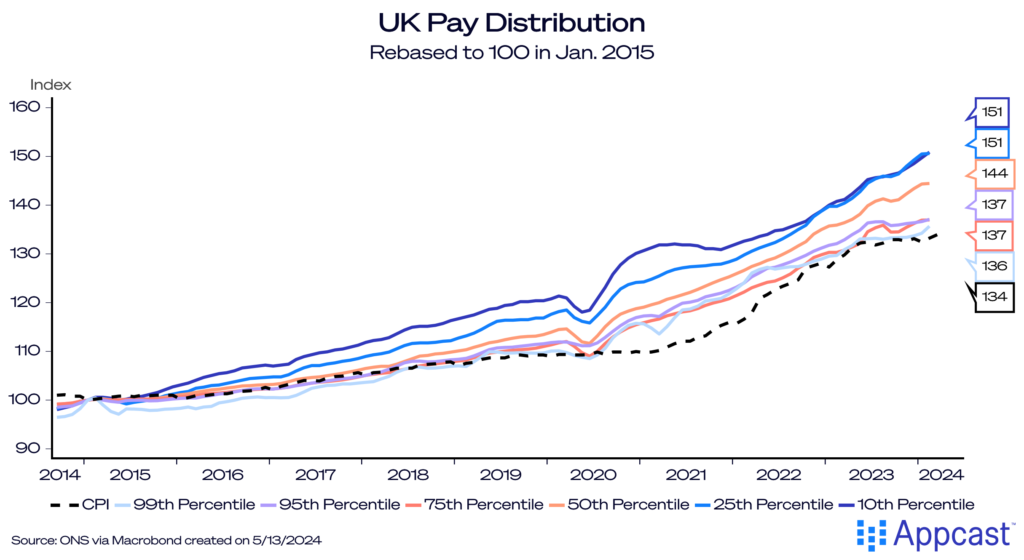

The relative outperformance of wages at the bottom has led to a wage increase of about 50% for the 10th and 25th percentile since January 2015. Meanwhile, the 75th, 95th and even 99th percentile have only increased by about 40% or less since then (all of these increases are nominal and therefore not inflation-adjusted).

Wages at the bottom in the U.K. pay distribution have outperformed by more than 10 percentage points over the last decade. Moreover, wages at the top have barely increased in tandem with inflation (the dashed black line).

The reason why wages at the bottom have performed so well is because the U.K. government has pursued an aggressive minimum wage policy. As the table below shows, the National Living Wage (the minimum wage for those aged over 21) almost doubled from £5.93 in 2010 to £11.44 in 2024. Many workers in sectors like hospitality and accommodation, food services, and retail trade are working for wages at or just slightly exceeding minimum wage. Employers like to boast that they pay above the threshold. Aldi U.K., for example, advertises that it pays more than the minimum wage. And Lidl, the supermarket’s competitor, just announced that they will follow suit and match Aldi’s pay.

This significant increase in the U.K. minimum wage can therefore explain why salaries at the bottom in the U.K. have outperformed as it shifts the entire distribution of lower incomes.

The large increase from £6.50 in 2014 to £7.50 in 2017, a 20% rise, corresponds with the same time period in the chart above when low-income salaries were growing faster. Similarly, the increase from £8.21 in 2019 to the current level corresponds to another 40% increase within just four years.

The lift in bottom incomes in the UK has therefore been quite mechanically the result of the government-mandated minimum wage.

Productivity stagnation can explain the poor performance of wages

So, the obvious question is: why have wages at the top of the distribution done so poorly?

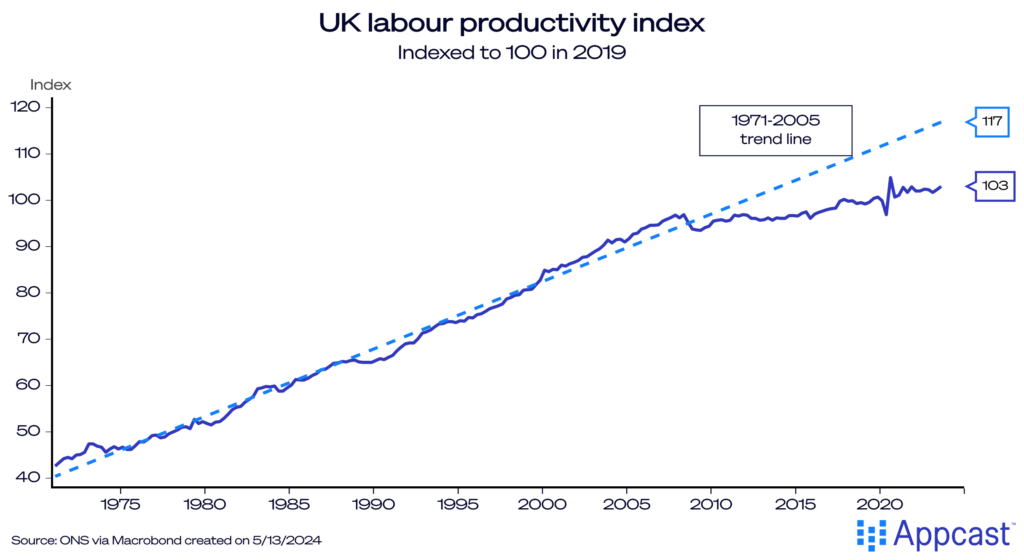

Well, the main reason is that the U.K. has a major productivity problem. Living standards and wages are basically a reflection of underlying economic performance. In the words of Krugman: Productivity isn’t everything, but in the long run, it’s almost everything.

Unfortunately, U.K. economic performance has been mediocre at best since the financial crisis.

While the underlying reasons are hard to pin down precisely, it is quite clear that the utterly dysfunctional housing market and the horrible U.K. planning system are contributing to the malaise. Nothing is getting built in this country! Moreover, there has been a massive lack of private sector investment in the economy in the decade following the financial crisis, with obvious implications for economic growth.

Other economic costs and benefits of a high minimum wage policy

For a society, it is not desirable if some workers are barely getting by. The high minimum wage policy should be therefore applauded from an equality point of view. Those earnings go to the people who serve us coffee, or maybe drive us around in a cab, or check our groceries in the store.

However, there is also no doubt that a government-mandated approach to rising wages can have side effects. A lot of research shows that minimum wage policies do not seem to lead to substantial negative employment effects as long as the minimum wage is kept below 50 to 60% of the median wage. This threshold is simply a rule-of-thumb though. The U.K. government is currently targeting 60% of the median income.

Most recent studies have failed to identify significant negative employment effects in countries with minimum wage legislation. However, that does not mean these don’t exist once the minimum wage gets sufficiently close to the median.

Other than the negative employment effect – employers reducing the number of people on payroll – there can also be negative effect on total hours worked. Employers can therefore reduce salary costs by adjusting two different margins, both of which hurt workers: either the size of the workforce or total hours worked.

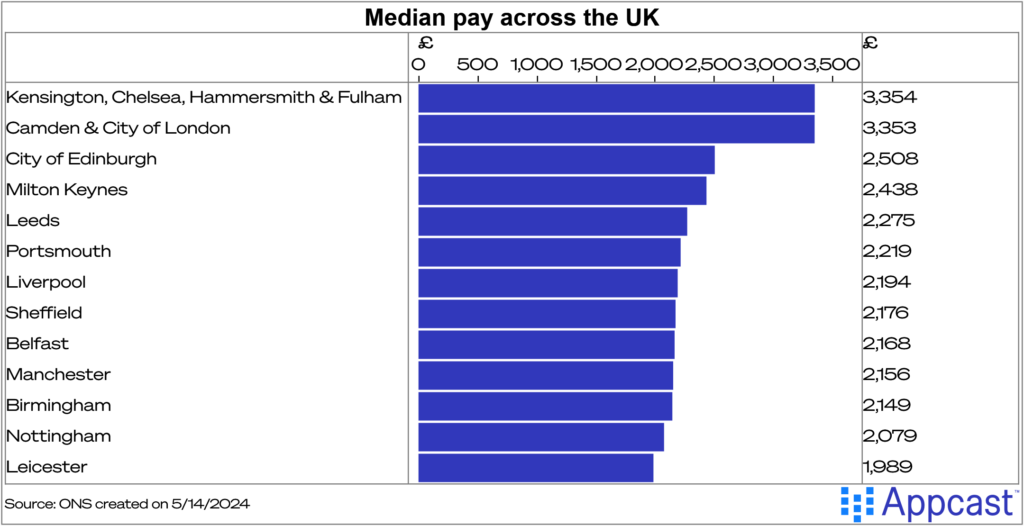

Another factor to consider is the large regional differences in wages across the U.K. As a matter of fact, the U.K. is one of the more unequal economies when it comes to geographic differences.

HMRC data shows striking salary differences across the country. While the median pay in the city of London stands at £3350, Northern cities like Nottingham and Leicester in the Midlands are only at £2000, approximately 60% of the London wage (note that these figures include all salaried employees, including those working part-time).

Despite those vast regional differences, the U.K. minimum wage obviously applies nationwide, regardless of income level. London employers will more easily be able to cope with a minimum wage exceeding £11 while businesses in poorer regions of the country might not.

After all, assuming a 35-hour work week, the minimum wage would yield a monthly income of about £1,600, or more than 80% of the median income in Leicester.

Many articles have recently highlighted the increased wage bill that small businesses are facing as a result, especially in the food and hospitality sector. According to ONS data, some 44% of workers in the sector are low earners.

Bloomberg highlights how pubs in particular are struggling from higher input costs, the wage component being the most important one. In Northern Ireland, many businesses will feel the impact of the legislation and will have to pass on some of the costs to customers (hospitality is a very low-margin industry). Generally speaking, businesses in lower-income regions will suffer disproportionately from the imposed increase in the wage burden.

The recent minimum wage hike troubles the Bank of England

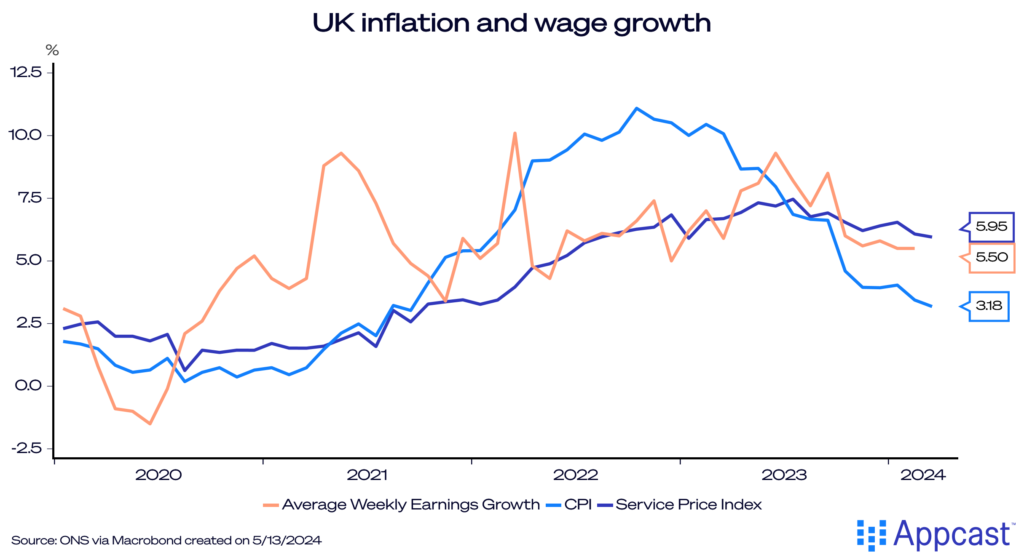

Another factor to take into account is that we are coming out of a highly inflationary episode following the pandemic, supply chain shocks, and the energy crisis.

The Bank of England (BoE) has been tightening monetary policy to bring inflation down back to target. Right now, monetary policy makers are still concerned about sticky wage growth and service price inflation (and the negative feedback loop between the two).

Service price inflation continues to increase at a rate of above 5%, far too high to be consistent with the BoE’s inflation target. And the same is true for wage growth, which is also still exceeding 6% right now.

And as we have seen above, a lot of the wage growth is being driven by higher income growth at the bottom, including the government’s legislated minimum wage hike.

As a result of higher than desirable wage increases from a monetary policy perspective, BoE policy makers will have to leave interest rates higher for longer. Higher interest rates, in turn, discourage business investment, overall spending, and reduce employment.

And that means that the current minimum wage hike might very well have a negative employment effect precisely because the BoE needs to counteract the rapid wage growth at the bottom.

Many workers will be better off thanks to higher wages, but some workers will not because employers reduce working hours or cut employment altogether to reduce their wage burden in a weakening economy. Sadly enough, there is no free lunch in this case!