Britain has been changed by 14 years of Tory government. The economy has mainly been stagnant during that period. Wage growth, adjusted for inflation, has been sluggish. Austerity in the aftermath of the financial crisis was a massive mistake, leading to years of subpar economic performance. Public services have deteriorated, especially the NHS. Brexit dealt another blow to the economy. Estimates suggest that it might shave off some 4% of GDP in the long run.

The economic recovery from the pandemic has been anemic, as well. Economic inactivity increased. Close to a million people have left the labor force, many of them due to long-term health issues. Housing unaffordability has never been as much of a problem as it is today. It is estimated that Britain is lacking more than four million housing units.

It is thus not a lie when Labour officials say that they inherited a terrible economic legacy. With government debt at its highest level in decades and interest rates above 4%, the government does not have a lot of fiscal space.

The Autumn Budget was probably the most important one in decades. The private sector had been eagerly awaiting the policy announcements ever since Labour came into power. Policy uncertainty has weighed on business investment and hiring in the months prior to setting the Budget.

There is absolutely no doubt that the Budget will take the U.K. economy in a different direction. Public spending is going up and so are taxes, but whether this approach will be more successful remains to be seen. This blog discusses the measures that have been announced and what they will mean for the labor market and hiring outlook.

The good

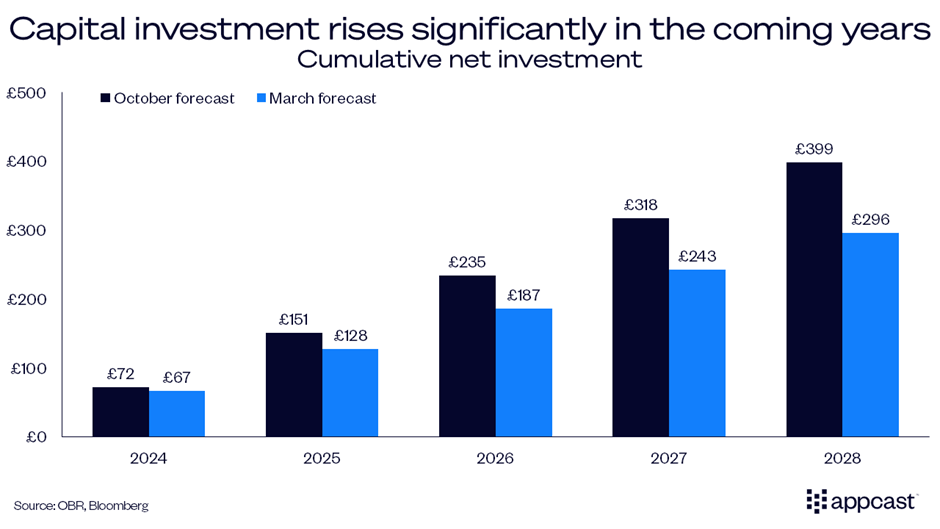

One of the biggest changes outlined in the Autumn Budget is the government redefining public debt. This is not just an accounting gimmick; it reflects the fact that the government does not just have financial liabilities (outstanding debt) on its balance sheet, but also assets. Similar to what is done in the private sector, it makes sense to take both assets and liabilities into account when assessing the health of public finances.

The new debt measure that is being targeted is called public sector net financial liabilities (PSNFL). It includes shares in public companies the government owns. It also comprises the outstanding value of student debt repayments and loans offered via Help to Buy schemes, for example.

This more inclusive metric shows that U.K. public sector debt is closer to 85% of GDP while the old debt measure stood at around 100% of GDP. Targeting PSNFL allows the Labour government to borrow more and increase public sector spending by more than £100 billion in the coming years.

And borrow they will! Labour announced an aggressive plan that includes an increase in the NHS’s day-to-day budget by £22.6 billion, with a £3.1 billion capital budget increase. An additional £100 billion will be invested in capital spending on education, infrastructure and defense over the next five years. Investment in schools, for example, is to rise by £6.7 billion, a 19 per cent increase in real terms.

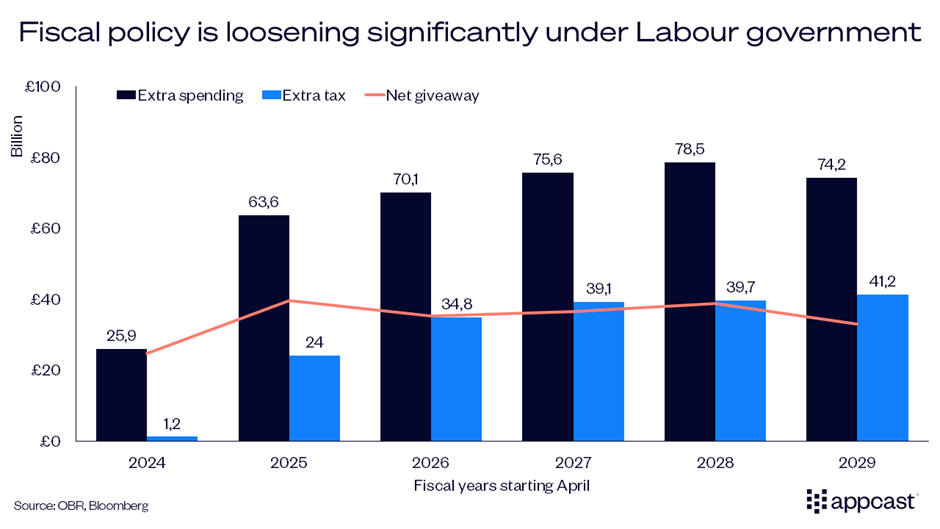

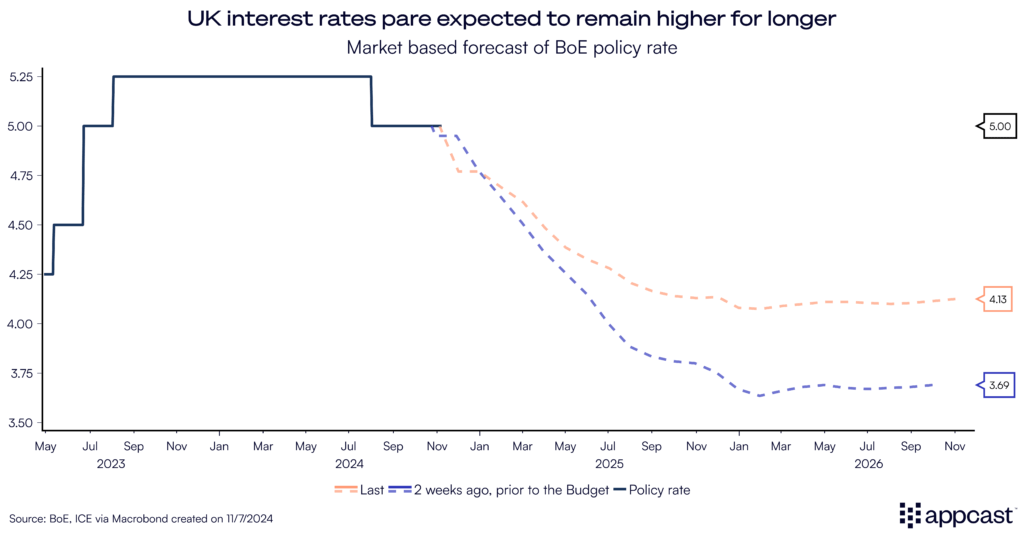

Fiscal policy in the U.K. is therefore loosening significantly. While more expansionary fiscal policy is likely to moderately boost growth, it also means that the Bank of England (BoE) will have to keep interest rates higher for longer to contain the inflationary boost from higher spending.

The bigger question is whether higher spending can improve the long-run outlook. NHS waiting lists have almost doubled since the pandemic. Important infrastructure projects were scrapped by the previous government (HS2). Fixing the healthcare system and addressing infrastructure needs may finally fix some of the supply-side issues the U.K. economy has grappled with for years. These measures will likely improve the growth outlook, but it will take years for the positive effects to materialize.

The bad

One of the promises from the current Labour government was to make housing more affordable. Demand for housing outstrips supply by several million housing units. Relative to incomes, both rental and home prices are significantly higher in the U.K. than in most other advanced economies.

While Labour has promised to address the supply-side issue and build more housing, it will take years for additional units to have a sizeable impact on market prices. Meanwhile, changes to stamp duty will translate to higher taxes for first-time home buyers, as the threshold after which stamp duty kicks in is being reduced from £425k back to its original £300k.

This is a significant additional burden for first-time buyers and makes housing less affordable. Remember that average house prices in the South East of England now stand at almost £380k (and more than £500k in London!), so few people will be able to avoid the tax in those regions.

The dysfunctional housing market has been one of the biggest barriers to stronger economic growth. It prevents workers from moving towards better economic opportunities in high productivity cities. Unaffordable housing is therefore distorting the labor market and Labour is not doing enough to fix the issue.

And the ugly

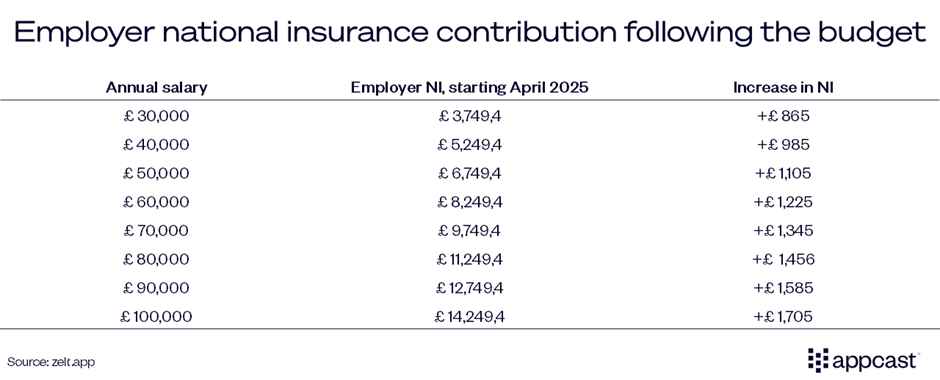

While Labour did not raise taxes on workers directly, it did so indirectly. The employer’s national insurance (NI) contribution increased from 13.8% to 15%. Meanwhile, the threshold at which employers start paying NI was lowered to £5,000 from £9,100. Not only does this significantly increase the cost of new hires, but it also raises the cost of current staff quite dramatically.

Starting April 1st, the cost of employing a salaried employee on £30,000 – slightly below median full-time wage in the U.K. – increases by a whopping £865 (close to 3% of the worker’s salary). Meanwhile, the cost of employing a worker earning £100,000 increases by only £1705, 1.7% of the person’s salary.

This means that businesses employing many low-wage employees will bear the brunt of the burden from the NI increase. Undoubtedly, some of the costs will be passed on to workers.

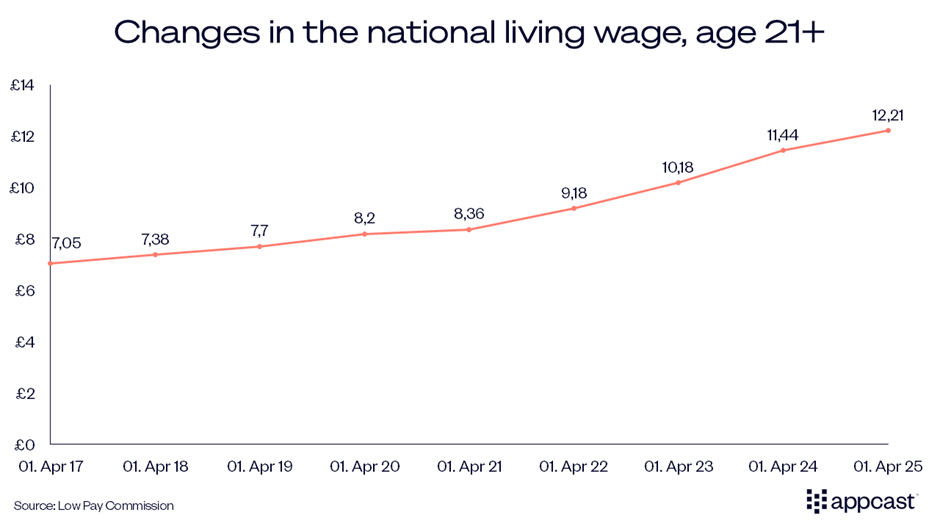

Furthermore, Labour decided to increase the minimum wage by another 6.7% to £12.21 starting on April 1st next year. The minimum wage for people aged 18-20 increases by 16.3% to £10. While lifting wages at the bottom is an applaudable policy goal, minimum wages have increased by almost 75% since October 2016! Meanwhile, wages at the top of the income distribution have increased by about 35%.

Especially in lower-income regions across the U.K., many employers will feel the burden of the higher minimum wage together with the increase in NI. Some of these costs will be passed on from employer to employees, meaning lower wage growth for workers going forward. Furthermore, some hires will become unprofitable. This will particularly be true for low-wage sectors, such as accommodation and hospitality. The NI increase and the higher minimum wage will thus be negative for job growth.

How are financial markets reacting?

Financial markets’ reaction to the Autumn Budget has been mixed. Bond yields surged last week, and expectations are that the additional fiscal stimulus is inflationary, which means that BoE will have to pursue a more contractionary monetary policy stance. Interest rates are now expected to remain above 4% all the way throughout 2026, compared to expectation before the Budget of a decline in interest rates to about 3.5% by early 2026.

Public spending will therefore crowd out private spending from businesses and households because of higher interest rates. The net effect on growth is therefore ambiguous.

What does the Autumn Budget mean for recruiters?

Employment costs will rise quite substantially as the result of the Autumn Budget, given the increase in employers’ NI contribution as well as the mandated increase in the minimum wage. Both combined mean that employing staff in low-margin sectors (think hospitality and accommodation, for example) has become more costly and potentially even unprofitable.

There is no doubt that some employers will have to make some tough choices. It is likely that some businesses might have to lay off some staff, given the tax increase in a challenging economic environment. The hiring outlook will also worsen following the Autumn Budget since companies will not be able recruit as many employees as previously assumed due to rising costs.

Last but least, the increase in national insurance also negatively affects workers. The business sector will pass on some of the rising costs onto employees. And what that means is that some workers can say goodbye to next year’s salary increase!