We recently published a piece on the U.K. economy in which we discuss the outlook for economic growth and inflation and what it could mean for the labor market and blue- vs. white-collar occupations.

In this follow-up post, we will dig a little deeper into the Bank of England (BoE) economic forecast, whether it is plausible or not, and what it will mean for hiring.

While a U.K. recession is highly likely, there is a lot of uncertainty on how deep and prolonged the economic downturn will be.

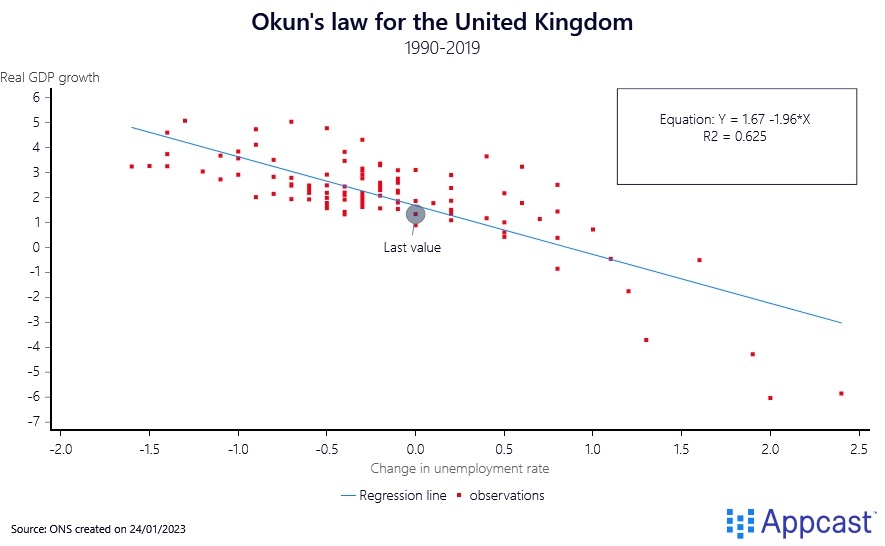

The chart below plots the relationship between economic growth and unemployment – what economists refer to as Okun’s law. What this scatterplot shows is that historically in the U.K. a one percentage point decline in GDP growth has been associated with about half a percentage point increase in the unemployment rate.

If GDP growth declines from plus 2% during an expansion to minus 2% during the recession, unemployment could thus easily rise by 2 percentage points or more.

While this relationship held up well during the decades before the pandemic, today’s labor market is fundamentally different. First, Brexit has led to an acute shortage of blue-collar workers in various industries with more than 300,000 workers missing.

Second, the decades before the pandemic have led to a continuous weakening of workers’ bargaining power, a result of declining union membership, rising globalization, and potentially increasing monopoly power.

However, recent research suggests that these trends are now slowly reversing. Wage growth has surged to a multi-decade high and labor markets across advanced economies have been super tight. An upcoming economic downturn will surely hurt workers but might not lead to a massive rise in unemployment as it did in 2008.

Forecasters have never disagreed this much

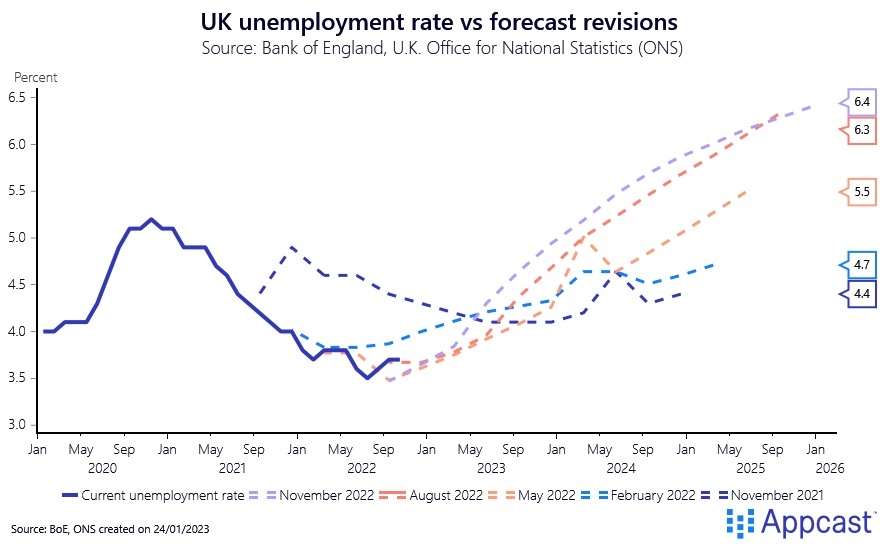

Economists are very much in disagreement on how the U.K. economy will perform over the coming two years. They have also revised their forecasts substantially over the last year, given the amount of global uncertainty.

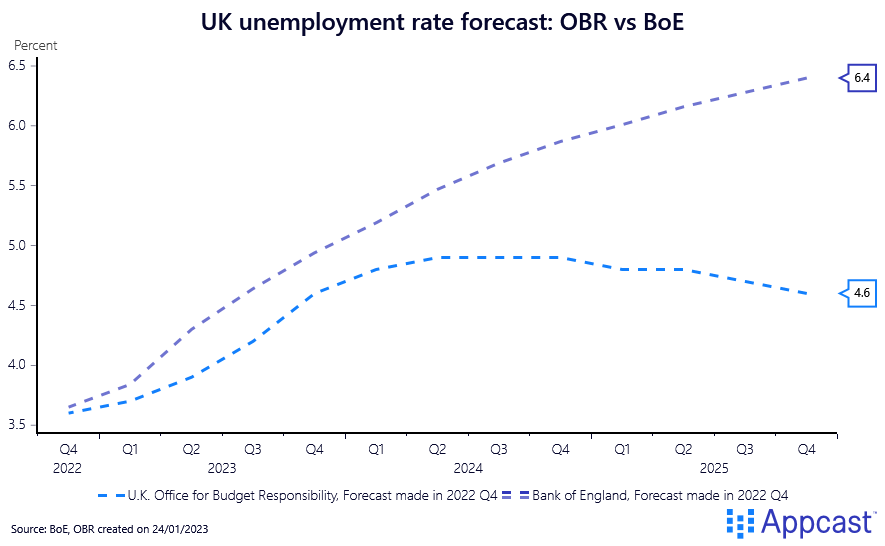

The BoE’s assessment has become increasingly pessimistic over time, now assuming a peak unemployment rate of more than 6.5% in 2025 compared to the November 2021 forecast, which assumed a peak of less than 4.5%.

To give you an idea of the divergence between various institutions, compare the BoE forecast to that from the Office for Budget Responsibilities (OBR).

According to the OBR, unemployment will only rise by more than one percentage point during the 2023 recession and peak at about 5% in early 2024, with a subsequent small decline thereafter.

How can we square those two widely differing forecasts? Well, the BoE is also much more pessimistic about the growth outlook. The Central Bank assumes both a steeper and longer recession – lasting a full six quarters – followed by a very timid recovery with real GDP growth remaining below 0.5% until mid-2025.

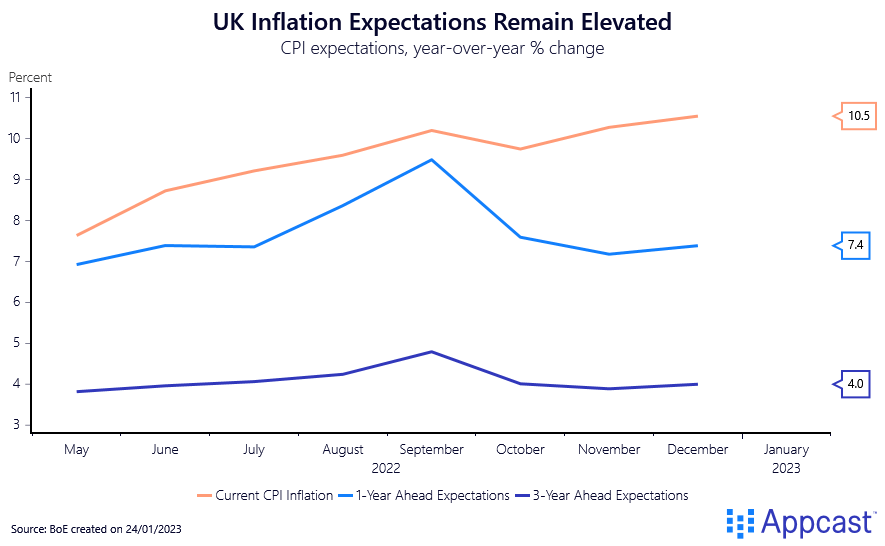

Why? One reason might be that short-run inflation expectations are still shockingly high. This is certainly frightening the monetary policy committee, and as of now the BoE seems to believe that creating a recession is the only way forward to bring those numbers down.

An engineered recession?

While this scenario is certainly plausible, it should be taken with a grain of salt.

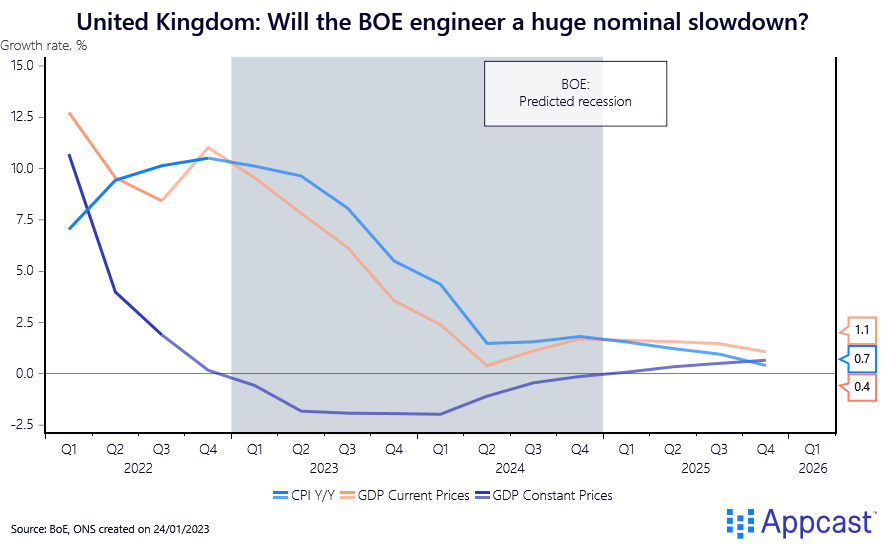

The BoE numbers show a rapid decline of nominal GDP growth from more than 10% as of last year to less than 2% in early 2025. Such a steep decline in total spending in the economy would indeed lead to a prolonged economic contraction. But the recession would be self-induced since it is monetary policy that steers nominal GDP growth of the economy.

It is not quite clear why the BoE would push for such a severe slowdown since 2% nominal growth is also incompatible with its own inflation target – unless one expects negative real GDP growth for years to come. However, there is no fundamental reason to be that pessimistic about productivity growth even with Brexit scarring the economy.

When all is said and done, I find the BoE forecast unrealistic, simply because the U.K. is already suffering from an enormous cost-of-living crisis as wages have stagnated for a decade.

The politics do not allow for the BoE to create a massive recession with a rapidly rising unemployment right now.

What does this mean for recruiters and the labor market?

There is no doubt that the U.K. slowdown will lead to an increase in unemployment, but it will most likely be more moderate than the BoE forecast suggests. Furthermore, as our last piece argues, blue-collar workers might not suffer this time around as much as they usually do during a recession because Brexit has led to massive shortage of unskilled workers. As of now, job postings have declined much more for some white-collar jobs like software development.

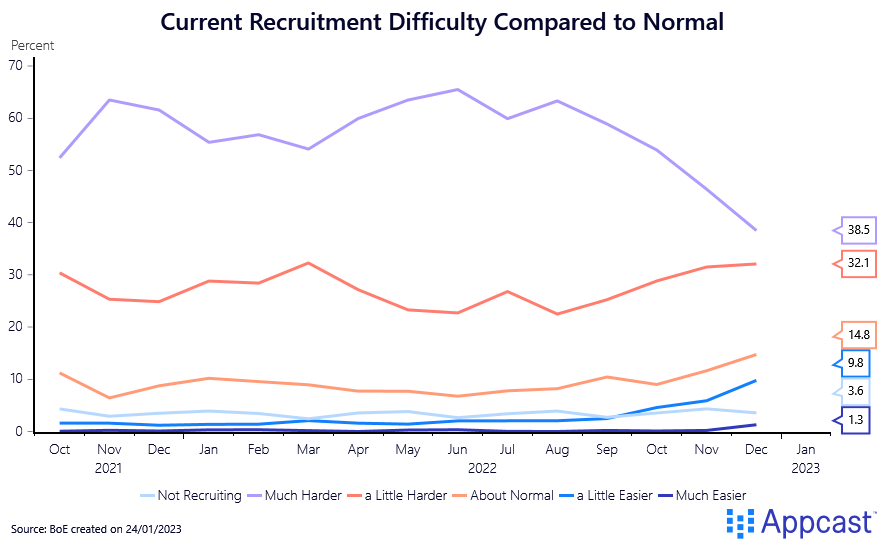

For recruiters, life has become easier since last year when the labor market was super tight and filling vacancies was more difficult. Compared to mid-2022 when more than 60% of respondents answered that recruiting is much harder, that number has declined to less than 40%. Meanwhile, more than 10% of respondents are now reporting that recruiting is easier or much easier. This number was below 3% for all of 2022.

The extreme labor market tightness of last year is disappearing and we are slowly getting back to normal.