While the DINK phenomenon (dual income no kids) has been especially trendy in the United States, it is not the only country in which couples are forgoing children because of high opportunity costs as I explained in a previous piece. Advanced economies are facing the same issue of declining birth rates, but some countries are more affected than others.

As it turns out, public policy and social norms are key. Countries with affordable child-care facilities and in which the share of household work between men and women is more equally shared have higher fertility rates. Another important factor is the earnings penalty for mothers.

What explains the difference in birth rates between advanced economies?

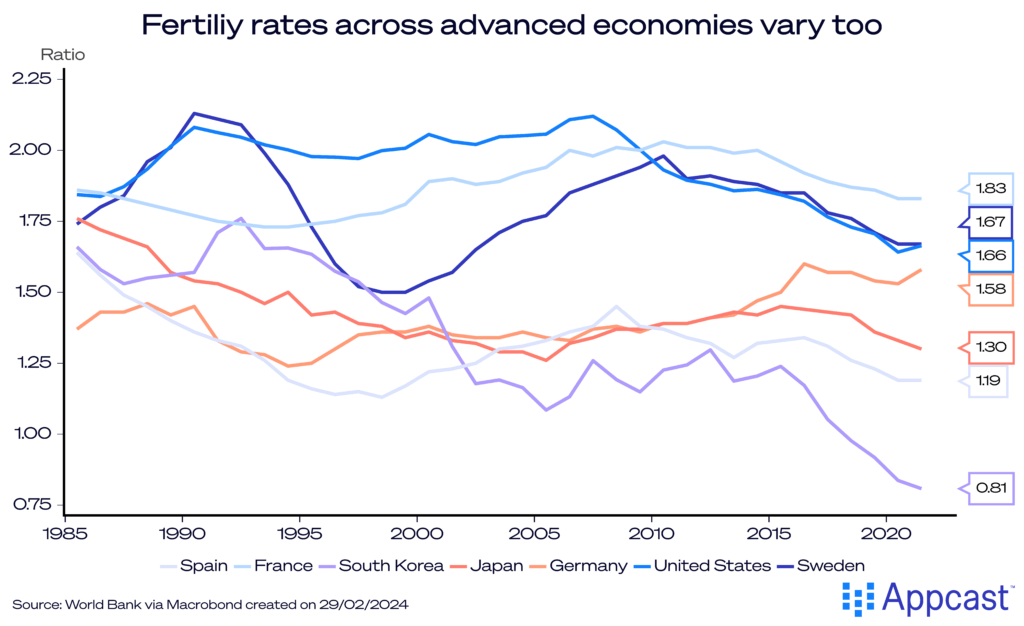

While the difference in fertility rates between high-income and developed economies is straightforward to explain, there is also a sizeable gap within the group of advanced economies today.

South Korea, Japan, and Spain have a birth rate below or close to one. The United States and Sweden, on the other hand, are two rich countries with birth rates almost twice as high.

How come?

Opportunity costs and social norms determine fertility

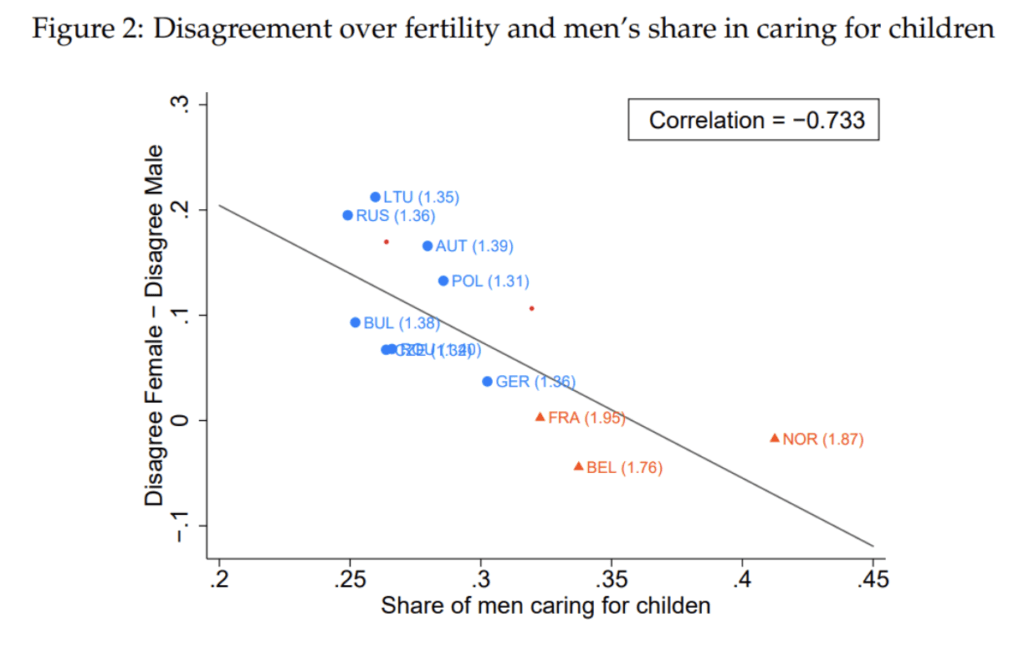

The variation in birth rates across rich countries can be explained by differences in women’s opportunity costs. It takes both a man and a woman to make a child. Unsurprisingly, the probability of conception declines dramatically if partners disagree on having children.

As it turns out, disagreements are high in countries where the men’s share in caring for children is particularly low, meaning that the woman would incur most of the burden at home.

Source: Bargaining over babies, Doepke and Kindermann (2019)

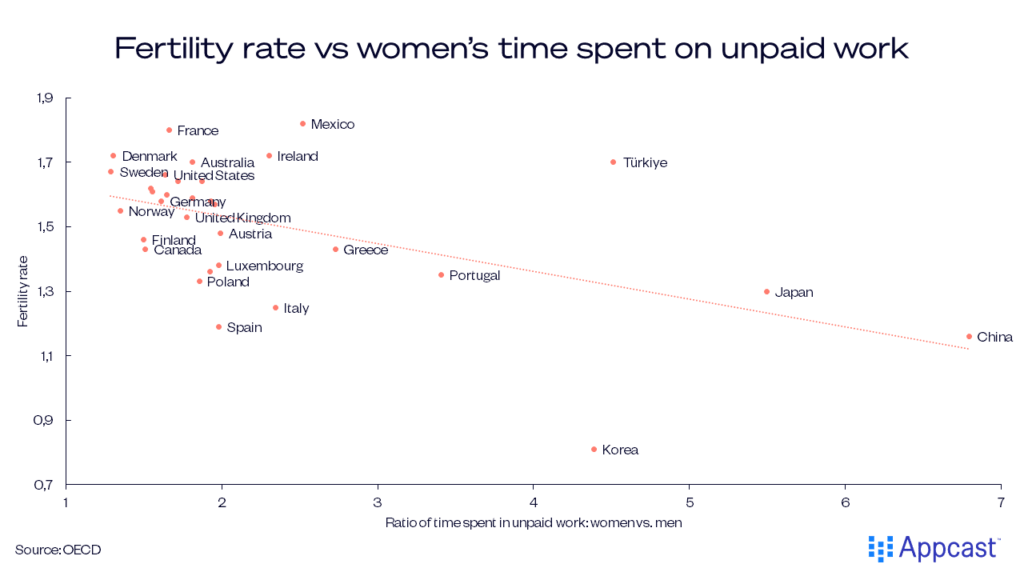

This is directly affecting fertility decisions. Countries in which household work is split up more equally between men and women also record higher birth rates. Unsurprisingly, fertility rates are the lowest in countries where women must spend much more time in unpaid work than men. This is more pronounced in some Asian economies like Japan and Korea but also Southern Europe where traditional gender roles remain more dominant.

Scandinavian countries are a great example where the childcare burden is shared more equally between partners. While there are also cultural factors at play, government policies certainly affect the burden that falls on mothers. Scandinavian countries have extremely generous parental leave policies that allows fathers to take on a big share of the work. Sweden allows 480 days in total for the two parents, and 90 days are exclusively reserved for each partner and cannot be transferred. According to Swedish statistics, fathers in Sweden currently average around 30 per cent of all paid parental leave.

The child penalty varies significantly by country

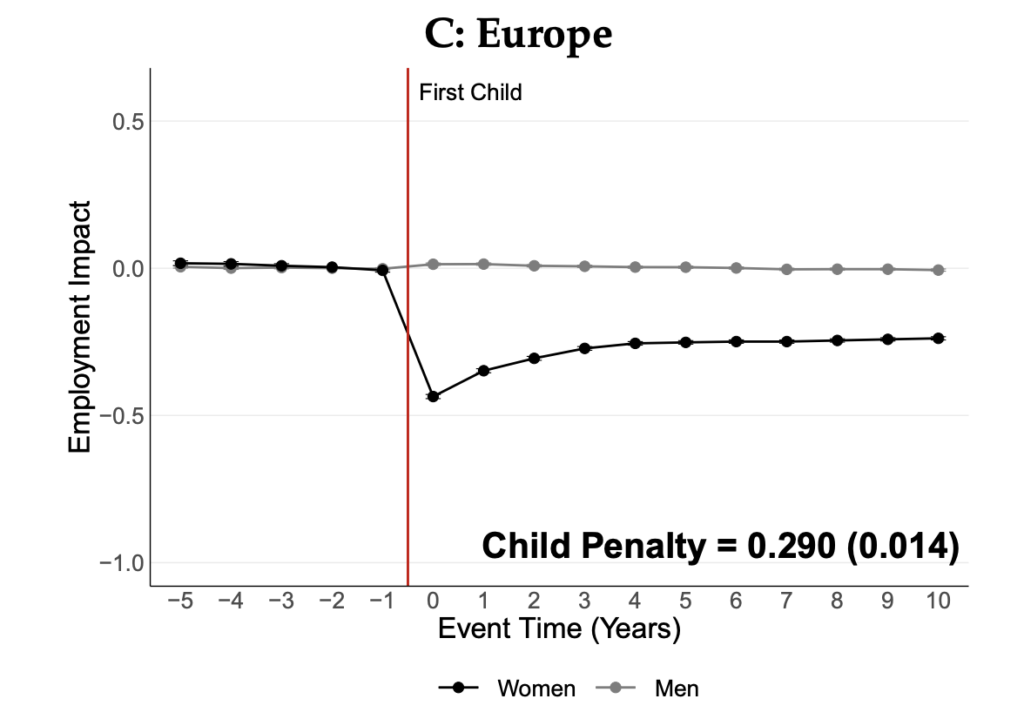

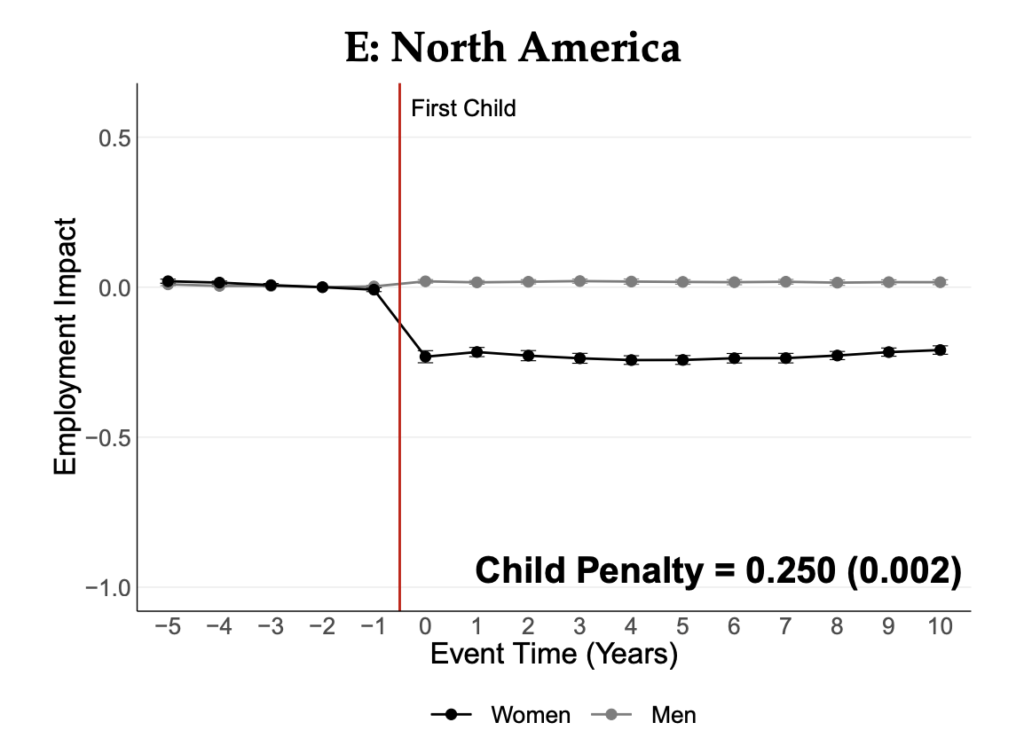

Another key factor that determines fertility rates among advanced economies is the child penalty. A recent article in The Economist summarizes the findings of an academic study estimating the employment gap that arises due to motherhood.

Women dropping out of the labor market after having their first child explains 80% of the gap between female and male participation rates in high-income countries. However, there are wide discrepancies between countries.

The average negative employment effect for the first ten years after the birth of the first child stands at around negative 40% in Germany, negative 33% in the U.K., negative 25% in the U.S., and less than negative 10% and negative 5% in Sweden and Norway, respectively!

Source: The Child Penalty Atlas, Kleven, Landais & Leite-Mariante (2023)

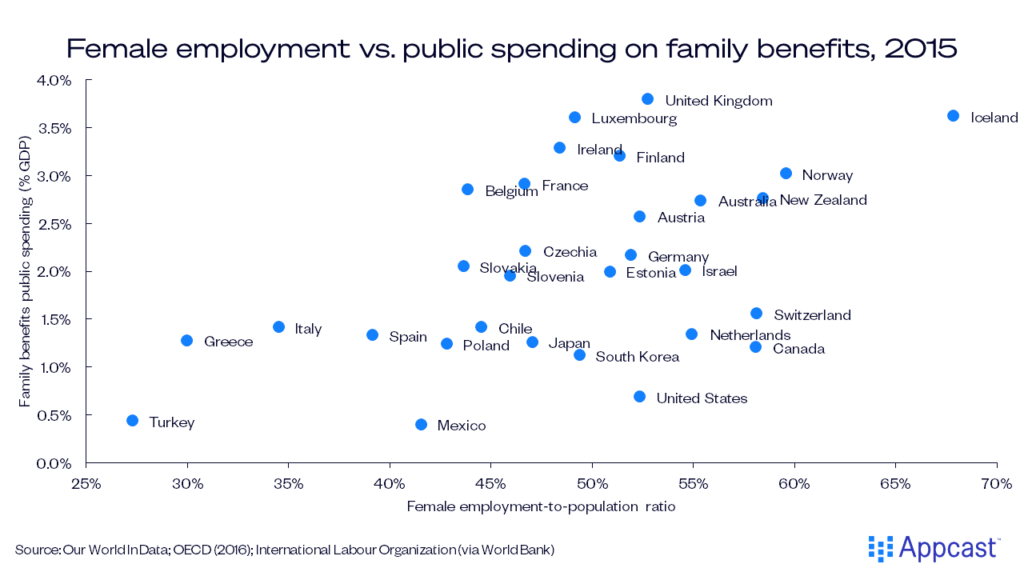

This penalty tends to be larger in countries like the U.K. where childcare expenses are prohibitively expensive relative to incomes. The Nordic countries stand out again as being extremely well-placed thanks to their generous childcare infrastructure. In Norway and Sweden, for example, childcare fees for kindergarten and pre-schools are a function of household income. Therefore, even low-income households can afford the expenses. Female participation in the labor market is generally higher in countries that spend a larger part of their budget on family benefits.

A study from 2009 compared the labor market outcomes of mothers in Germany, the U.K. and the U.S. The research found that mothers in the U.S. behaved in a more market-oriented way. American mothers take significantly less time off for childcare than their European counterparts and are also less likely to enter part-time roles. This suggests that women in the U.S. are acutely aware of the labor market structure and adjust their behaviours accordingly as to minimize the child penalty.

To be or not to be (a DINK)?

A couple does not become a DINK by accident. They are driven by the unique opportunity costs they face in their home countries, which include the availability of cheap childcare, shared parental leave, and public spending on family benefits. Women are more likely to have children if household work is shared more equally between partners, and more importantly, if the wage penalty and career sacrifice that comes from dropping out of the labor force to become mother is kept to a minimum.

If advanced economies like the U.S. and the U.K. adopted more child-friendly policies seen in Scandinavian countries, more couples may choose to forgo the DINK lifestyle, rather than children.