The U.S. economy has seen a spectacular recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. Economic growth has outpaced most other advanced economies by a substantial margin. The labor market has also recovered well from the economic recession that coincided with the lockdowns in the first year of the pandemic. Employment in the U.S. is exceeding its pre-pandemic peak by about 5.5. million. Last year alone, more than three million jobs were added, an average of close to 300,000 net new non-farm payroll jobs each month.

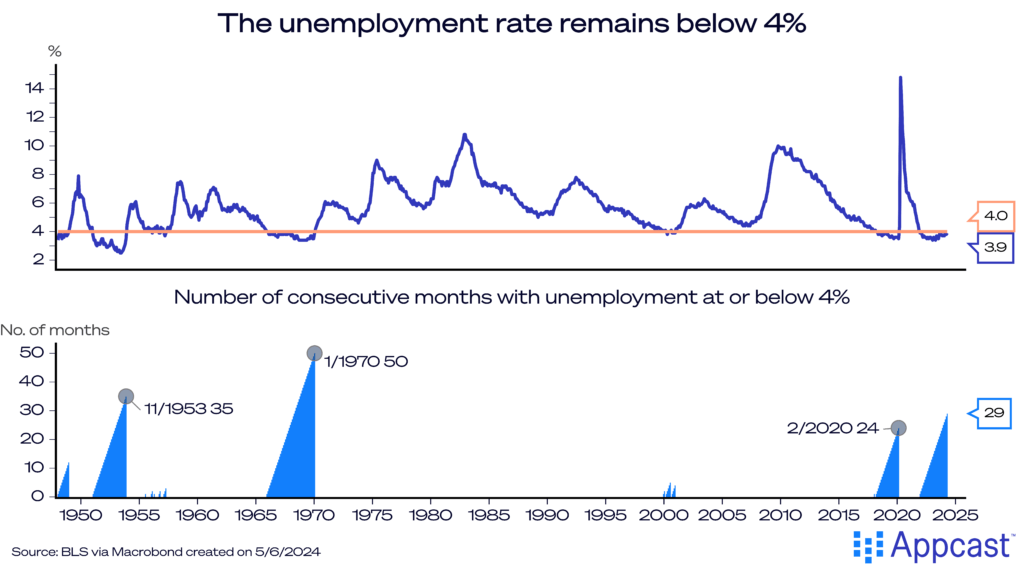

That number far exceeded economists’ consensus estimates back in late 2022. Then, economists expected only half the strength per month. Record-high immigration numbers helped to shatter expectations and supported the jobs boom. The unemployment rate is experiencing a record-long spell of below 4%, something not seen since the 1960s. While inflation has been at its highest in decades, nominal wages have more than kept up, meaning real wages have increased as well since 2020.

Given the high pace of job creation together with a record streak of low unemployment, people have been wondering whether this is the best labor market ever for workers.

A great labor market is not just characterized by record-low unemployment. There are a variety of other metrics that should matter for workers’ bargaining power: Real wage gains and living standards in general are probably front of mind. But job security, appreciation for the work you do, having an interesting job, and the benefits and perks your employer offers on top of the salary are all part of workers’ well-being.

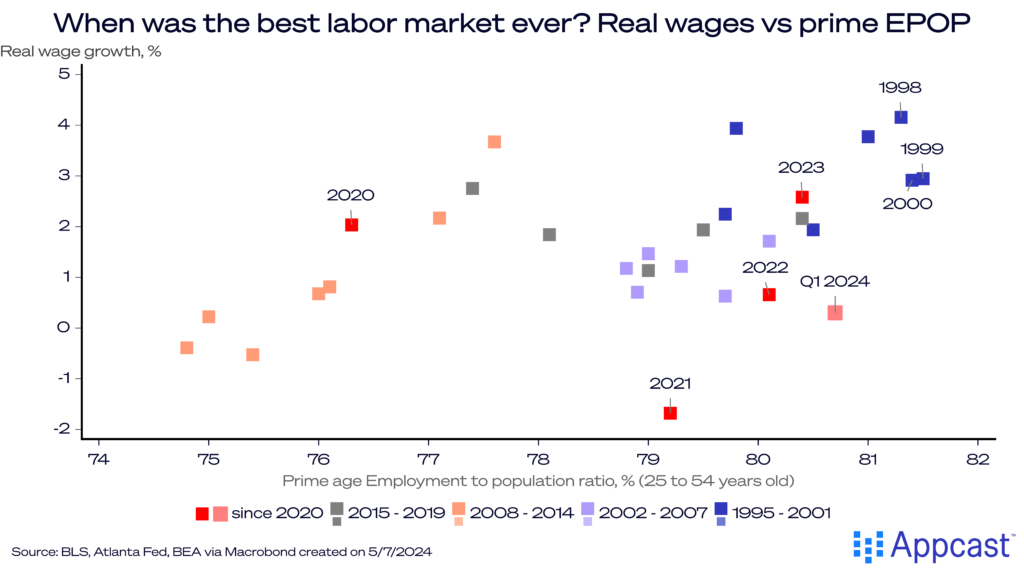

For simplicity though, we will focus on two metrics that seem to matter the most to evaluate whether the labor market is good or bad for workers: the prime-age employment to population rate (how many workers in that age group are being employed) and real wage growth.

Judging by era

The chart below plots the two variables since 1995 with real wage growth on the y-axis and the prime-age employment-to-population ration on the x-axis. For real wages, we use the Atlanta Fed’s nominal wage growth series and deflate it with the Personal Consumption Expenditure (PCE) index, the Fed’s preferred measure of inflation. The chart also clusters the different points by time periods. While simplistic, it offers some really great insights into some of the macro regimes we have experienced since then.

First, the period of the early 2000s coming out of the Dot-Com was satisfactory by decent economic performance. Prime-age employment was just a little under 80% and real wages were growing at a rate of about 1 to 1.5%, not terrible but also not spectacular. It was a decent labor market for workers from 2002 to 2007!

The period of the Great Recession and its aftermath was very different. The U.S. was stagnating for years coming out of the financial crisis. The labor market was very weak and generally bad for workers. Prime-age employment was low and remained depressed for years. To top it off, real wage growth was sluggish. Basically, employment opportunities were bad and increases in living standards were marginal: a pretty horrible labor market for workers from 2008 to 2014!

The period from 2015 to 2019 saw the U.S. economy finally recover and edge closer towards full employment. Prime-age employment finally exceeded 80% again in 2019 and real wage growth during that period was closer to 2% with workers enjoying more respectable increases in living standards. The labor market rapidly improved from 2015 to 2019, approaching pretty good status!

The COVID-19 period is obviously all over the place. Employment plunged in 2020 but then quickly recovered. Real wage growth was negative during 2021 but then surged as nominal wage started to grow faster than inflation. 2023 was generally a great labor market with a prime-age employment rate exceeding 80% and real wage growth of more than 3%. This year, the employment rate is even higher but real wage growth will be somewhat lower. It’s been a pretty great labor market since 2021, but is the best?

The best labor market ever was during the Dot-Com boom in the late 90s! Prime-age employment exceeded 81% from 1997 to 2000. Furthermore, real wage growth was running at around 3%. The combination of full employment with real wage gains above 3% makes it the most spectacular labor market for workers in recent history!

Other labor market indicators confirm that the 1990s was a great time for workers

If you think the chart above is too simplistic, then feel free to check it against a number of other labor market metrics which tell us the same thing.

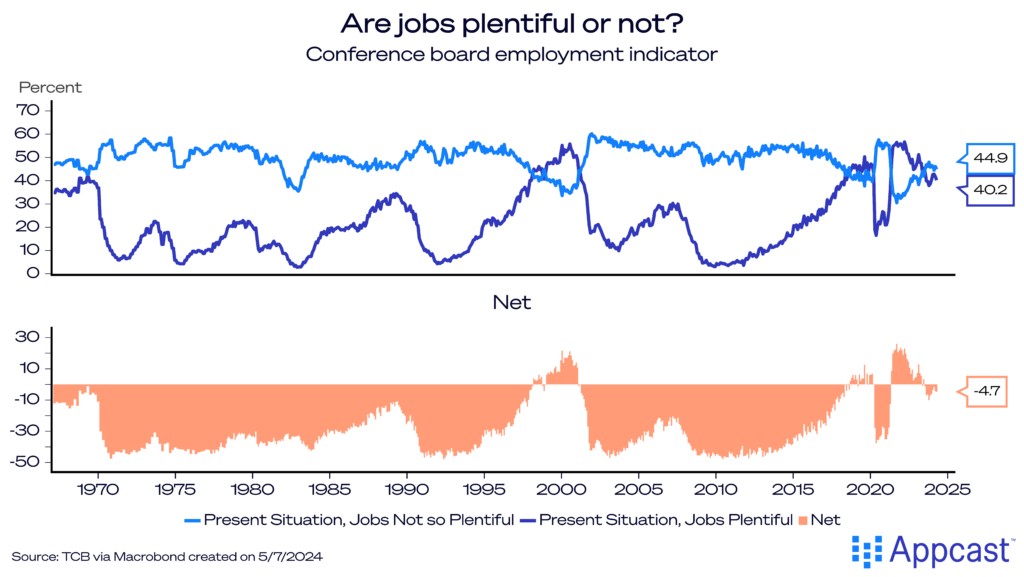

The Conference Board Employment Index surveys workers whether jobs are currently plentiful or not so plentiful. Generally speaking, there are only a couple of years when more people think jobs are plentiful, 2019 and the economic recovery from COVID-19 among them (2021 and 2022).

But, again, the late 1990s sticks out as the longest stretch of plentiful employment opportunities.

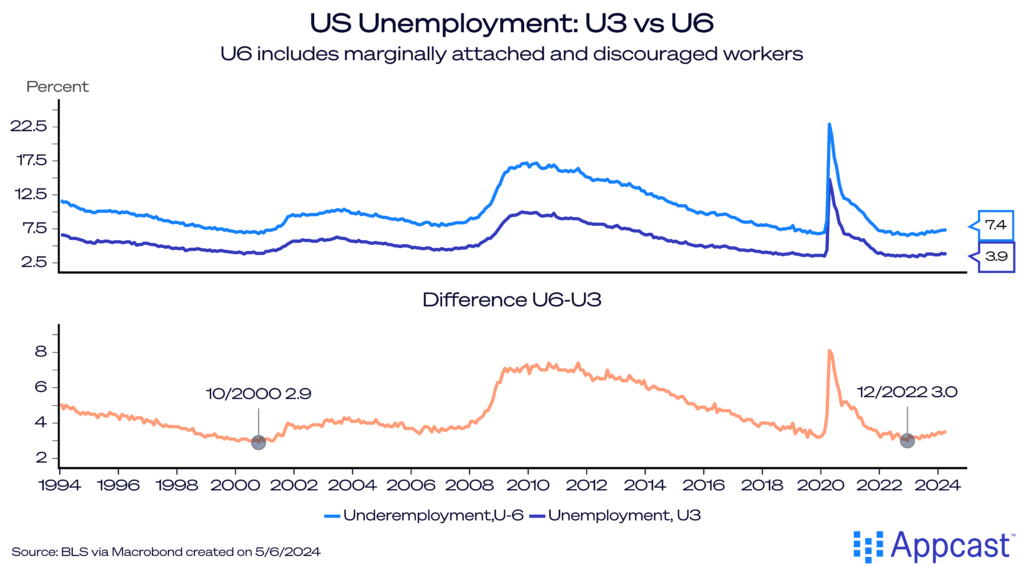

Further showing the strength of the 1990s are alternative measures of the unemployment rate. U6 is a more inclusive measure of unemployment that includes marginally attached workers and discouraged workers. The former refers to people who are available and want to work but have not looked for employment in the prior four weeks, while discouraged workers are those who have given up looking for work.

Again, the late 1990s and 2000 stand out as a particularly strong labor market. The difference between U3 and U6 fell to below 3% in late 2000, meaning that there were very few marginally attached or discouraged workers at the time. A hot labor market!

It’s worth noting, though, that both 2019 and the recovery from COVID-19 have come very close. Indeed, in 2022, U6 even temporarily dipped below the 2000 value. Hopefully, this healthy labor market could continue for some time. Signs are very promising that the U.S. economy will continue to grow steadily or even above trend this year and that the Fed will achieve a soft landing.

Full employment is a great thing: It benefits both workers and the economy as a whole. There is some evidence that during periods when the bargaining power of workers is improving and wages are rising, companies tend to introduce more labor-saving technology (automation). This in turn feeds into long-run economic growth and improvements in wages and living standards. A rising tide lifts all boats and everybody wins!