Outperforming expectations but underperforming peers

While the U.K. economy has vastly outperformed growth expectations set last year, it needs to be said that the bar was pretty low. More than a year ago, the Bank of England (BoE) was expecting a severe economic downturn together with rapidly rising unemployment.

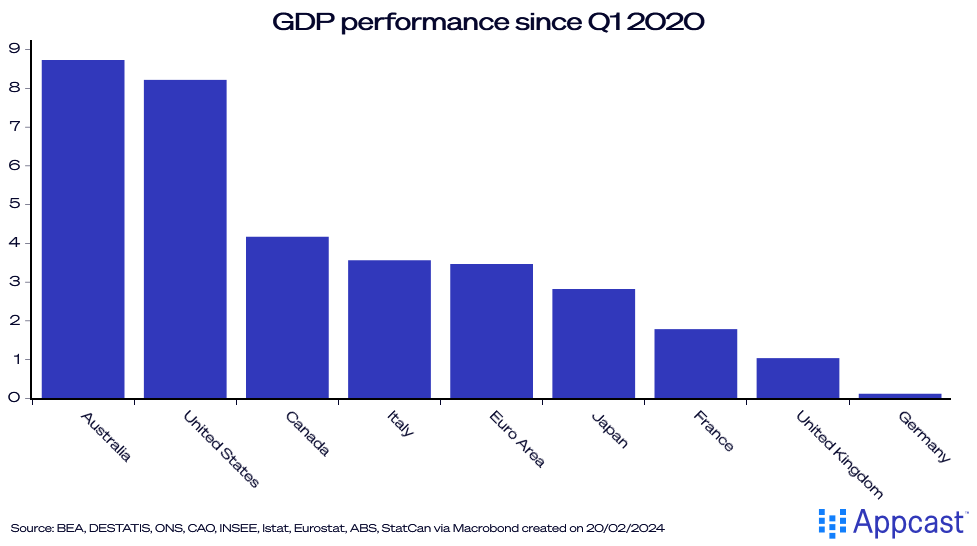

This severe downturn did not happen, but GDP data now shows that the U.K. economy did indeed experience a technical recession in the second half of 2023, as it experienced two consecutive quarters of negative growth. Total growth for 2023 is just barely positive thanks to slightly better performance in the first half of the year.

Moreover, GDP growth is now underperforming that of many other advanced economies. GDP today is less than 2% larger than it was in Q1 of 2020 and per capita GDP has actually fallen since then. So, we are basically in year four of economic stagnation.

Why is the BoE is still concerned about inflation?

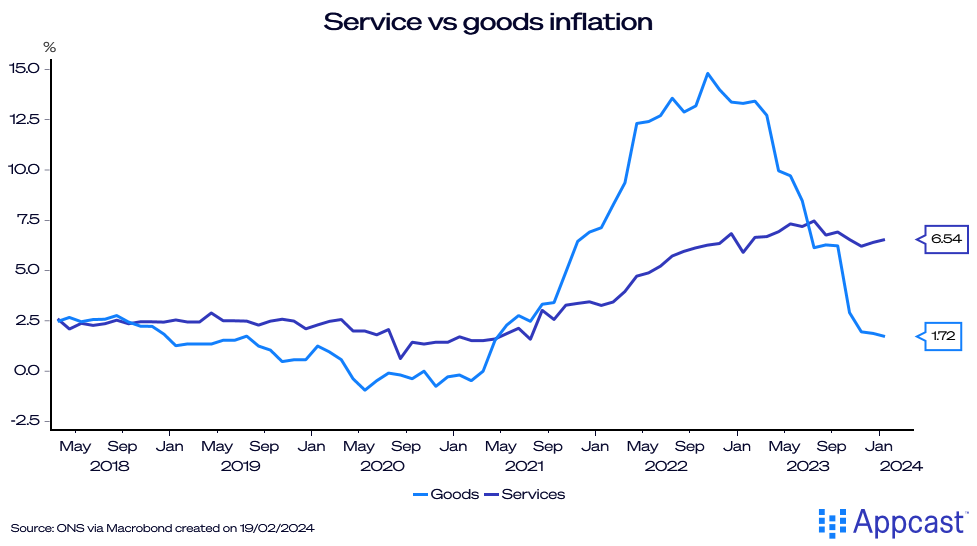

If the economic downturn persists, it will definitely put more downward pressure on inflation. However, the inflation rate is currently still twice as high as the Bank of England’s official two percent inflation target.

While goods inflation has fallen from more than 12% at the end of 2022 to below 2% more recently, services price inflation remains significantly higher. This is concerning for monetary policymakers because the service sector is a substantial share of GDP. Additionally, services prices tend to be more “sticky,” meaning that they are unlikely to fall as quickly as goods inflation even during a downturn.

One of the main reasons for this stickiness is that wages are the most important input for many services in the economy. Think about haircuts, cab rides, or eating out at a restaurant. The wage rate of workers in the service sector will play a big part of what you will end up paying.

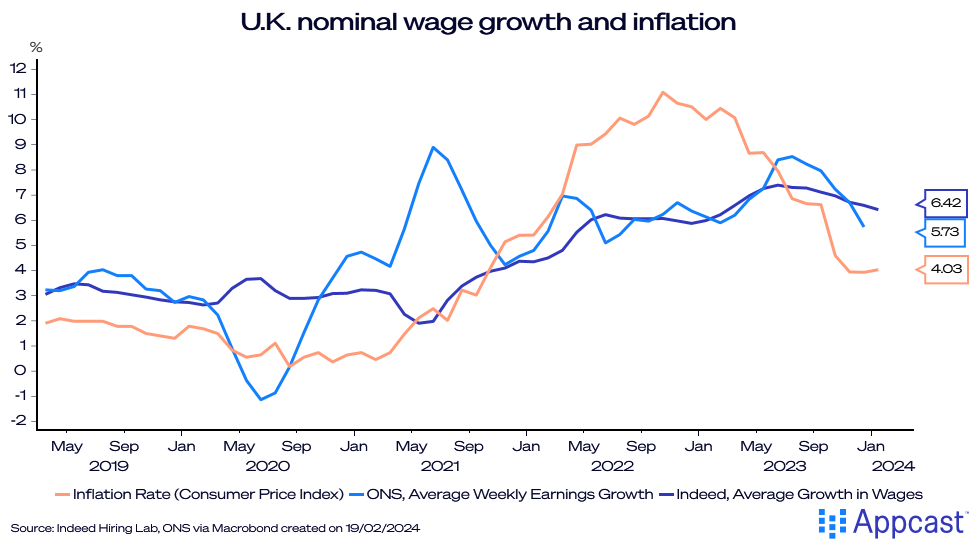

Nominal wage growth has remained relatively sticky even as the economy has not grown at all last year. Data by the ONS shows that wage growth is slowing but remains comfortably above 5% for now. Indeed’s wage growth measure shows an increase of more than 6% for new hires. Both measures will probably have to come down more before the BoE is willing to cut rates. With a 2% inflation target, nominal wage growth needs to be closer to 4% (assuming 2% productivity growth, which is optimistic because productivity growth has been disappointing in recent decades).

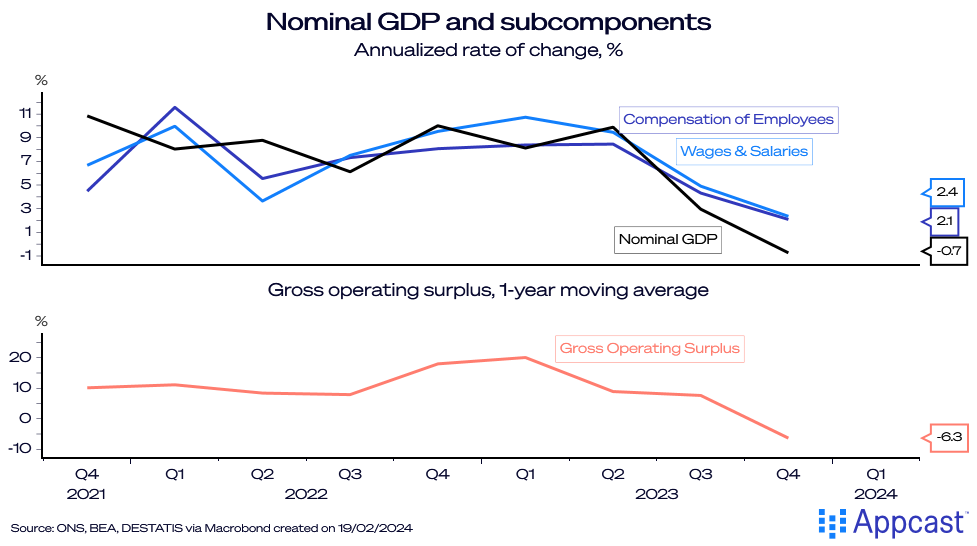

However, looking at the GDP data in the national accounts reveals a more worrying picture. Most recessions in advanced economies are caused by economy-wide slowdowns in the demand for goods and services – supply-side shocks like energy crises are more uncommon and tend to do less damage.

Since nominal GDP measures the total sum of goods and services produced, a big slowdown thereof usually indicates an upcoming recession. It also indicates that monetary policy has become too tight.

Nominal GDP slowed down from more than 8% at an annualized rate in the beginning of the year to 3% in Q3 and to minus 0.7% in the fourth quarter. While part of this is due to an unusual steep decline in the gross operating surplus (the value added by the corporate sector after subtracting workforce compensation), the economy-wide wages and salary component of GDP has slowed down to just over 2% in nominal terms. It previously stood at 4% in Q3 and more than 9% in the beginning of the year.

If not halted in due time, such a broad decline in aggregate salaries will lead to an economy-wide slowdown in spending and therefore, by definition, a recession.

The labor market has been holding up … so far

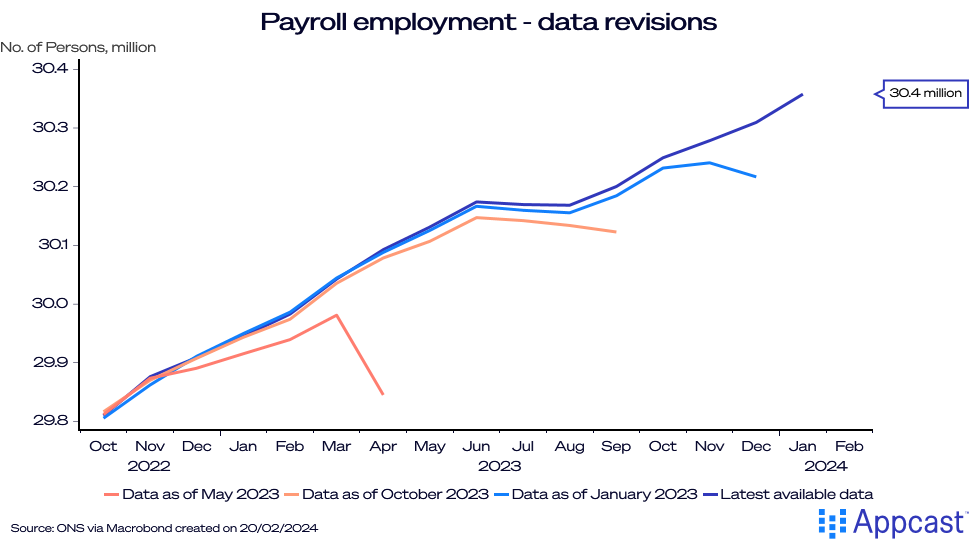

The one piece of good news is that the labor market has been holding up quite well so far – even as there are some doubts about the ONS unemployment rate figure. However, we know that payroll employment increased by about 400,000 last year. Moreover, previous declines in the data have been revised up.

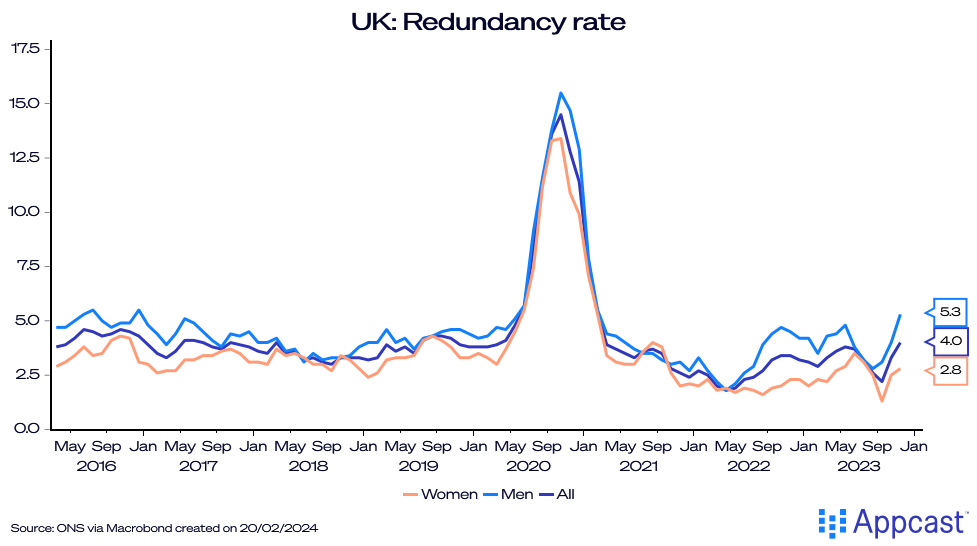

However, payroll employment growth slowed at the end of last year. Moreover, redundancy rates are showing an uptick in recent months. More and more companies in the U.K. are implementing hiring freezes or actively laying off people; white-collar workers are in tech and finance are currently more affected.

And vacancies continue to decline rapidly even as they are still above pre-pandemic levels.

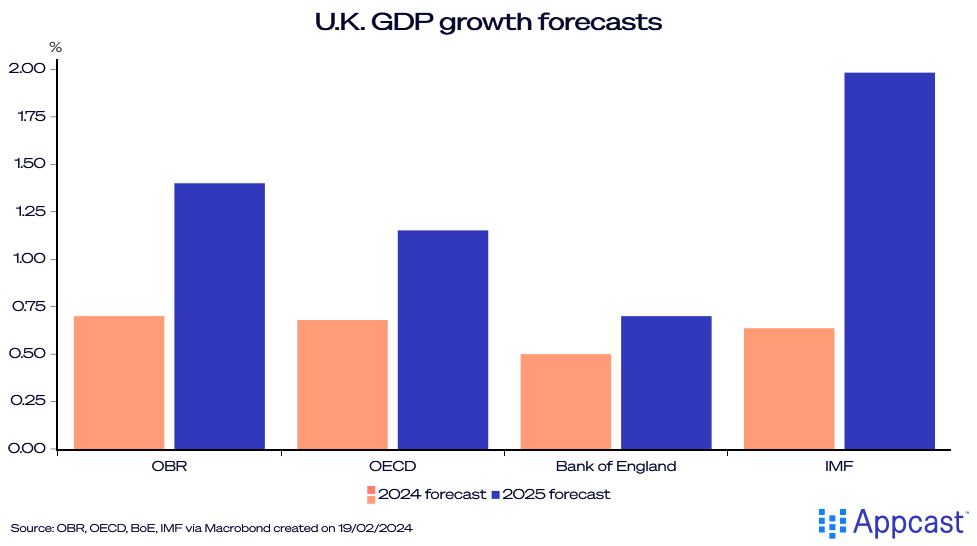

Economists are currently still projecting a little over 0.5% real growth for the U.K. economy for 2024. However, this forecast is highly dependent on the Bank of England’s monetary policy stance. It now seems more likely than not that the current interest rate is far too restrictive for the economy and will cause a substantial slowdown or even recession. Monetary policy makers need to wake up to this reality quickly or face the consequences of a broad economic and labor market downturn that would cause a more severe recession than the shallow downturn of last year.

Conclusion

The U.K. economy slowed down somewhat faster than expected at the end of 2023. The technical recession is less consequential than the severe slowdown in nominal GDP (and compensation of employees), which is pointing towards a broad-based decline in incomes across the economy. This will eventually feed back into declines in spending and cause an economy-wide downturn.

While the labor market has been holding up so far, there has been an increase in redundancies recently and corporate insolvencies are rising too.

The demand for workers is derived from the demand for goods and services in the economy. The economic and the labor market outlook will be highly dependent on monetary policy in the coming months.

We believe that the BoE will now have to reverse course and start cutting rates faster than anticipated to avoid an economic downturn in the first half of this year.