Sectoral employment shares have fluctuated wildly during the pandemic

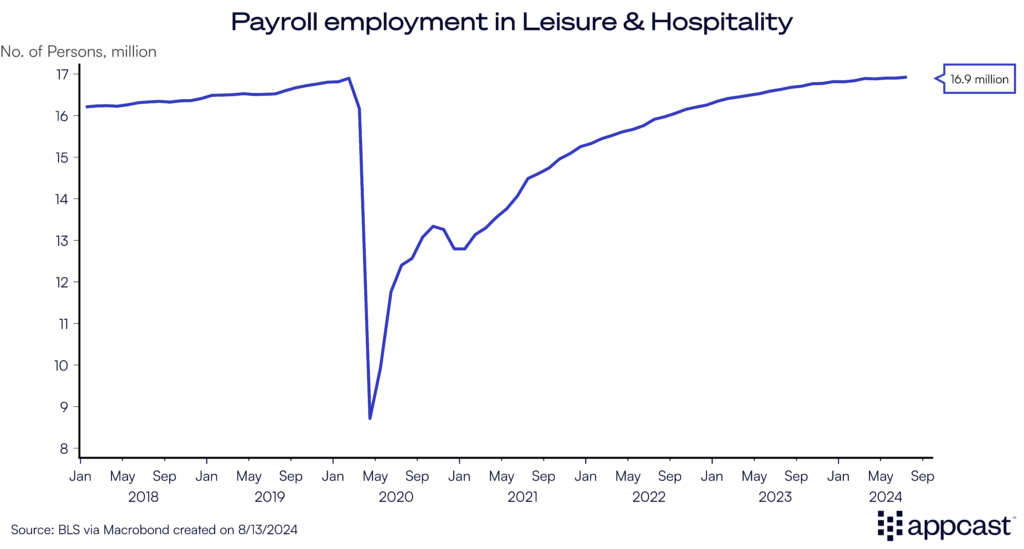

Remember when COVID-19 first took the world by storm, bringing the global economy to a screeching halt? The labor market was thrown into chaos, with some industries bearing more of the brunt than others. Among the hardest hit were the hospitality and food service sectors, in which countless workers found themselves jobless overnight.

Then, the vaccines arrived, offering a beacon of hope and a chance for economic revival. As the world economy began to recover and the intermittent lockdowns ended, the hospitality industry began to thrive again. Consumers were trying to catch up on lost time and forgone experiences. In the U.S., they were also swimming in cash thanks generous stimulus checks.

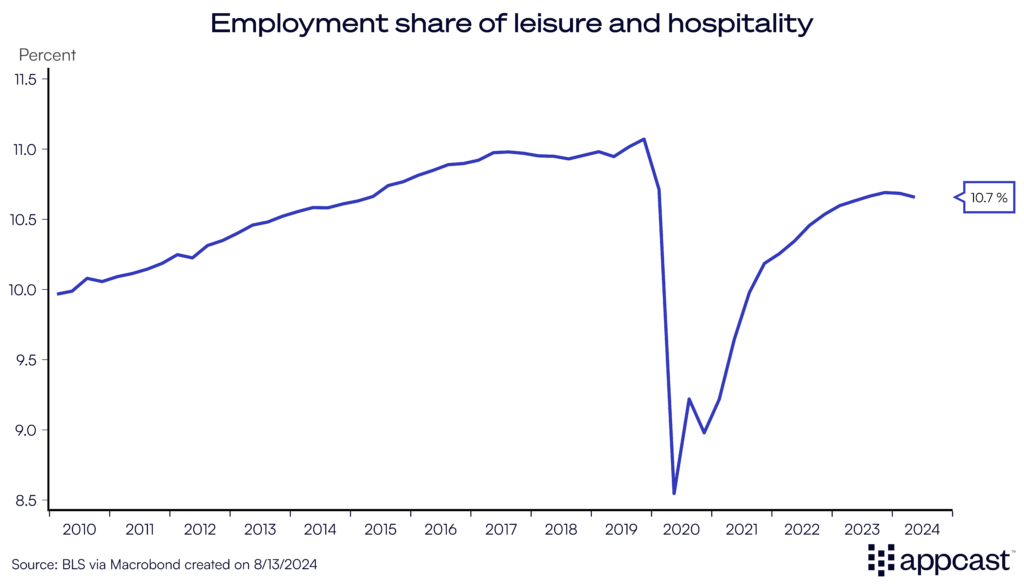

The employment share in leisure and hospitality had plummeted from close to 11% of all payroll jobs to less than 9% in late 2020, as some six million workers lost their jobs in the sector during the early stages of the pandemic.

With the economic recovery, the employment share has recovered to above 10% but remains noticeably lower than in 2019. Though rejuvenated, the sector is now facing a new challenge: A shortage of workers who have moved on to other industries that potentially offer better pay and benefits.

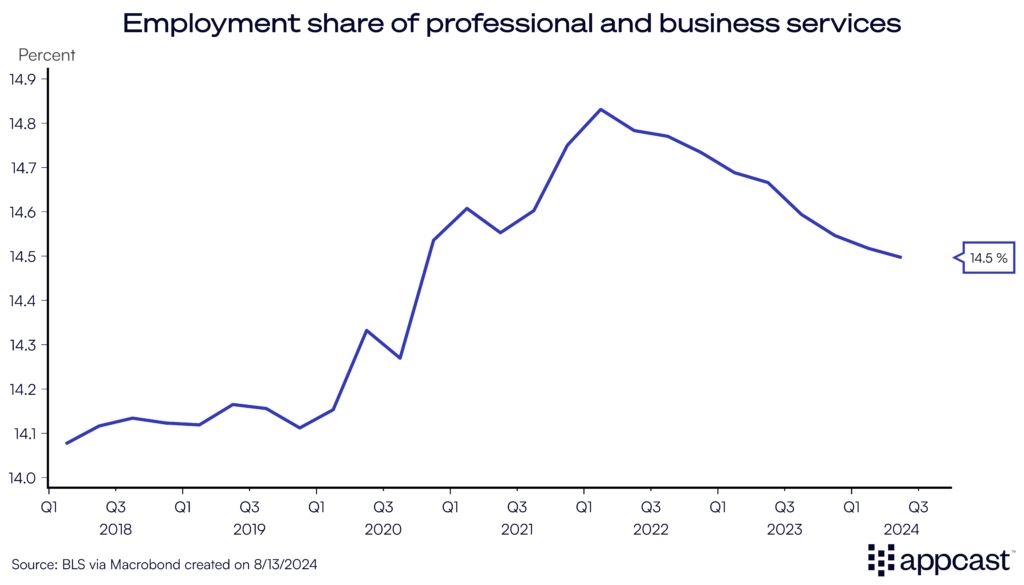

Meanwhile, white-collar workers experienced an unprecedented boom during the economic recovery of 2021 and 2022. The demand for workers in professional and business services soared. This includes people working in consulting, media and advertisement, marketing, legal services, and many more of what we sometimes call “sitting-down jobs”. Between late 2020 and early 2021, the employment share in this sector increased by almost one percentage point.

The decline since 2022 corresponds with the start of the “white-collar recession” that several advanced economies have experienced over the last two years. As central banks rapidly hiked interest rates to bring down inflation after the pandemic, white-collar jobs have been significantly more affected by the slowdown in demand, especially since there was an element of over-hiring in the space throughout 2021.

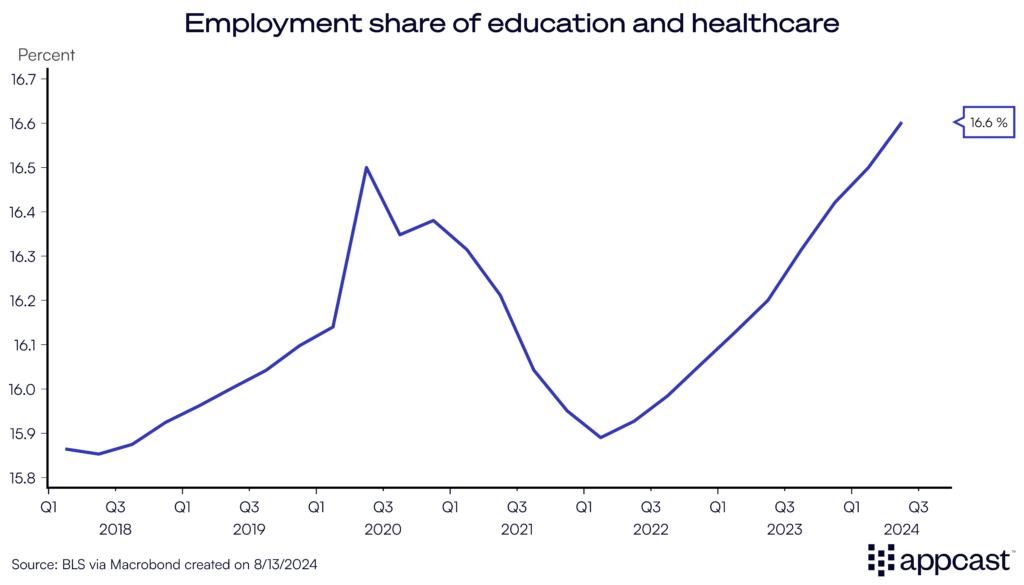

The share of workers in education and healthcare first declined during the pandemic but has recently surged to an all-time high. Healthcare has been one of the best-performing sectors in terms of net job creation over the last couple of years.

The “Great Reallocation”

The extent to which sectoral employment shares have fluctuated since 2020 is unprecedented. This is, of course, a result of the pandemic itself, which has arguably been the largest macroeconomic shock since the 1930s. It completely changed the outlook for various industries and our way of working (think about hybrid and remote work). It also caused a massive reallocation of workers between sectors, the “Great Reallocation,” if you will (yes, we are trying to make this the next buzzword).

Workers quickly shifted away from hospitality and retail as those two sectors were heavily affected by the lockdowns. As the economy recovered and the labor market became extremely tight, worker churn increased as employees were looking for higher salaries and better employment opportunities. The so-called “Great Resignation” led to the highest amount of worker churn ever seen. Unsurprisingly, this also coincided with the surge in salaries during the cost-of-living crisis. Job switchers generally see higher wage gains than workers who stay put.

The flexibility of the U.S. labor market was first considered to be a negative when unemployment surged to close to 15% in April 2020 when the pandemic hit. But in retrospect, it might turn out to be one of the greatest advantages that the U.S. economy has. The current productivity boom in the United States may have been supported by that reallocation in recent years, while Europe’s stagnant market could be holding back productivity.

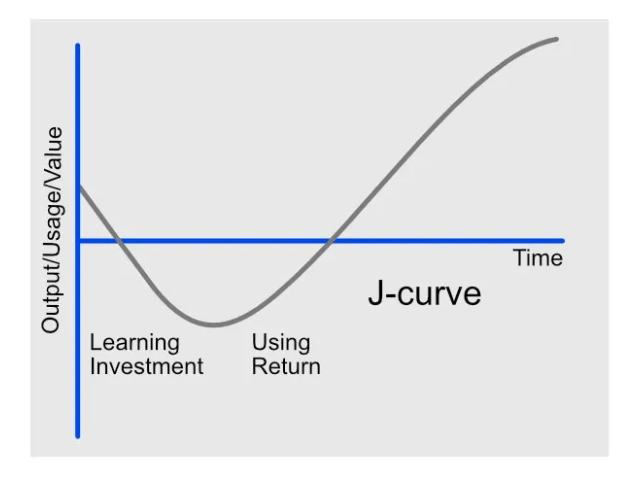

The productivity J-curve

When a worker changes to a new job, individual productivity typically follows a pattern of initial decline followed by an eventual increase due to the learning curve. The effect can be broken down into several stages:

- Initial Decline: When a worker first starts a new job, they are unfamiliar with the specific tasks, processes, and work environment. This unfamiliarity leads to lower productivity initially as they learn the ropes.

- Adjustment Period: As the worker becomes more accustomed to their new role, their productivity starts to improve. They begin to understand the workflow, the tools, and the expectations.

- Learning and Mastery: Over time, the worker’s productivity increases as they gain proficiency and confidence in their tasks. They become more efficient and can handle more complex responsibilities as they start to master their new role.

Based on the stages described above, worker productivity is behaving in a J-curve pattern following a jobs switch.

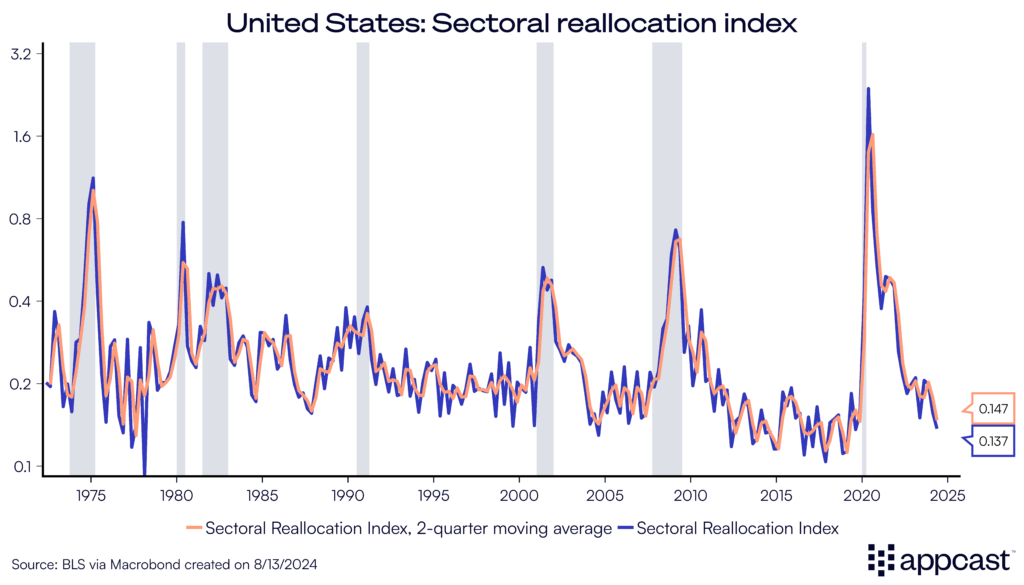

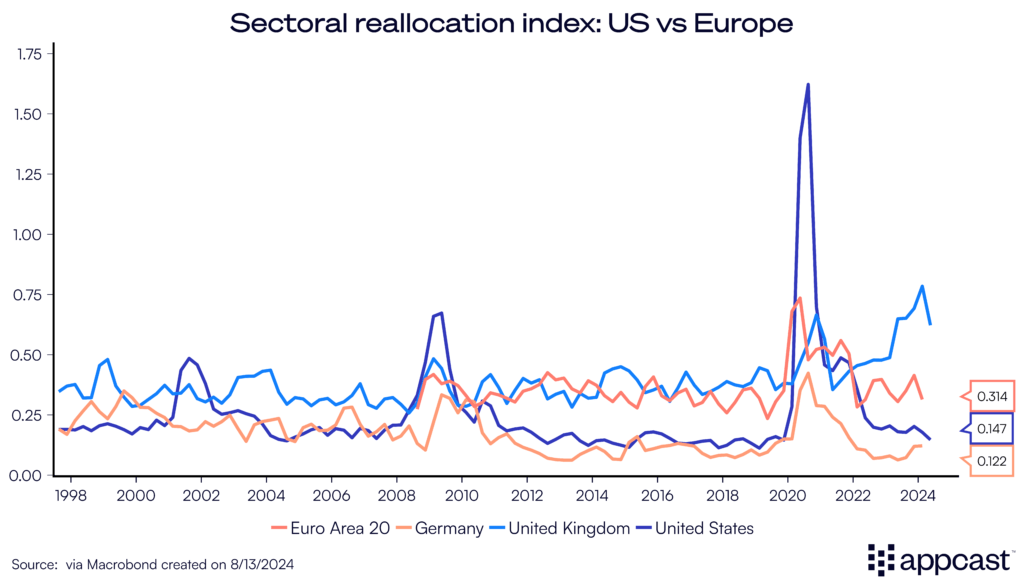

Based on research from the Chicago Fed, we calculated a worker reallocation index for the U.S. labor market. The index, based on changes in the sectoral employment shares over time, indicates the degree of worker churn between different industries: The higher the index, the larger the amount of worker reallocation in the labor market.

As one can see, the pandemic stands out as having the highest degree of worker churn since the 1970s (note that the axis is in logarithms and therefore even understating the extent to which COVID-19 period is an outlier).

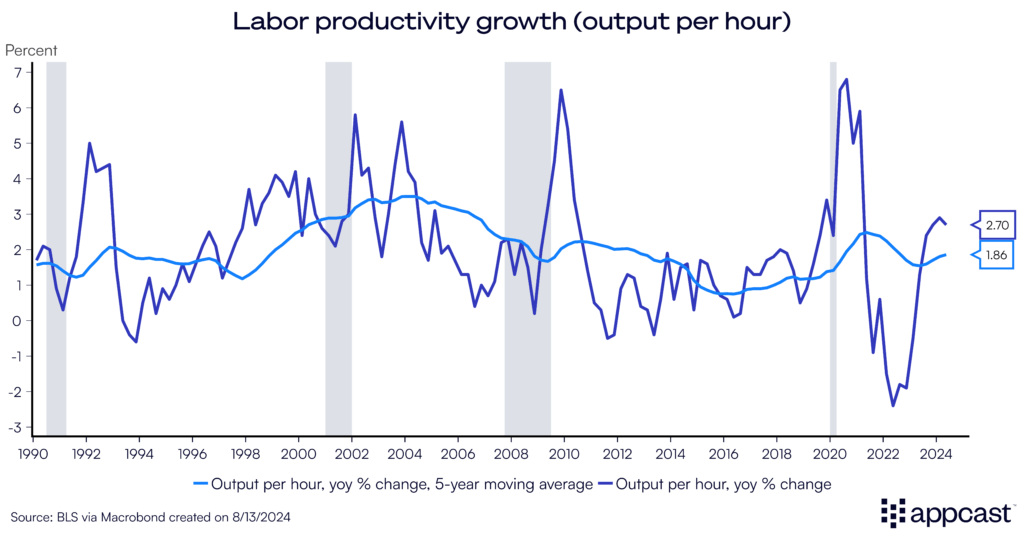

And just as one would expect from theory, productivity growth initially plunged in the U.S. throughout 2021 and 2022, the period coinciding with the highest amount of worker churn in the labor market. Now, more than a year later, as workers have transitioned to other employers and familiarized themselves with the tasks they need to succeed in their new roles, productivity growth has recovered and even accelerated again. This is obviously great news. And just as the J-curve would predict, worker productivity growth is now surged above pre-pandemic levels. The great reallocation of workers across sectors has improved aggregate matching in the labor market as it allowed many workers to move into higher-paying jobs that better fits their skills.

Europe, on the other hand, has not benefited from a similar trend because sectoral churn remained much lower. During the pandemic, European governments relied to a much greater extent on furlough schemes, which helped to maintain the relationship between workers and their employers. Unemployment rates across Europe therefore stayed at relatively low levels throughout 2020 and 2021. Once the lockdowns were over, workers returned to their previous place of work. While this was seen as a positive at first, it might have prevented European economies to reap the same productivity gains that the U.S. economy is now experiencing in the aftermath of the labor reallocation shock.

Note: The level of the index is not strictly comparable across geographies because the number of sectors differs slightly by country. It is therefore better to focus of the rate change during the pandemic, which shows a much larger increase in the U.S than in Europe.

Conclusion

The U.S. experienced an unprecedented amount of worker churn during the pandemic. While this probably depressed worker productivity at first, it seems like the effect is contributing to the current growth spurt. The more flexible and adaptable U.S. labor market turns out to be one the great strength of the U.S. economy. It is normal for workers to need some time to familiarize themselves with all the tasks a new job entails. But productivity increases as workers become more proficient within their role over time. There is a good chance that the “Great Reallocation” that happened during the pandemic has improved the matching between workers and employers in the U.S. labor market. And now that the transition phase is over, the economy is reaping the benefits from higher productivity growth, very much as the J-curve would predict. Let’s hope this effect will not be too short-lived!