Silicon Valley Bank’s failure from a lightning-quick bank run on March 10, the second largest in US history, has spooked financial markets. The Federal Reserve, with the help of the Treasury and FDIC, attempted to ease the panic on March 12 by announcing that all uninsured depositors would be made whole and unveiled a loan program to backstop other banks. But – on March 13 the stocks of mid-size regional banks plummeted, evoking memories of past financial crises. Interest rates declined sharply, under the assumption that the Fed’s year-long cycle of aggressive rate hikes has peaked. Financial contagion surpasses inflation as priority #1, right?

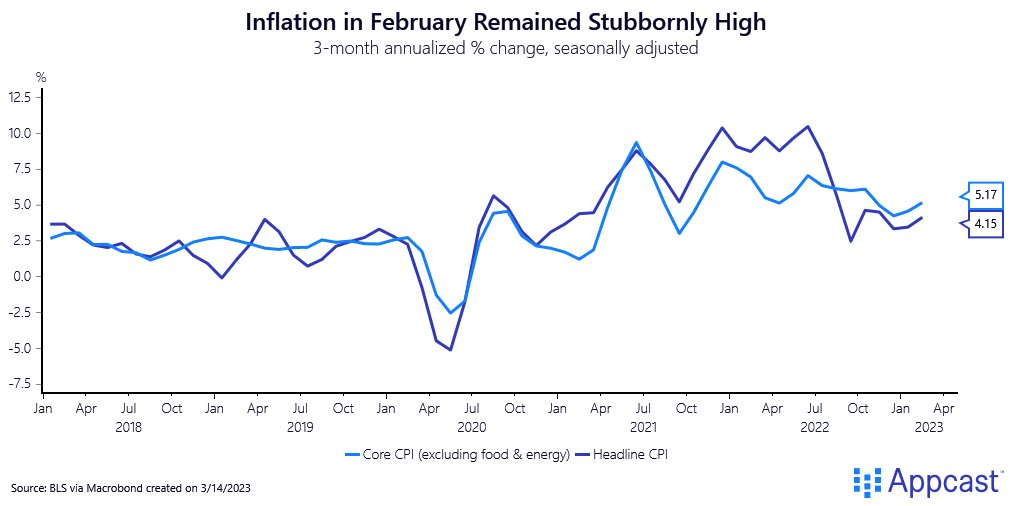

Not so fast. On March 14, the latest Consumer Price Index (CPI) numbers were released and inflation remains stubbornly high. While the rate of price increases is decelerating in year-over-year terms, growth ticked up over the last few months. “Core” CPI, excluding volatile food and energy components, increased to a 5.2% annualized rate over the last three months.

Energy prices have come down considerably from their highs in mid-2022, and goods prices continue to normalize after the peak chaos of clogged supply chains. That is the good news. The bad news is two types of prices are keeping inflation entrenched at a high level: housing and services.

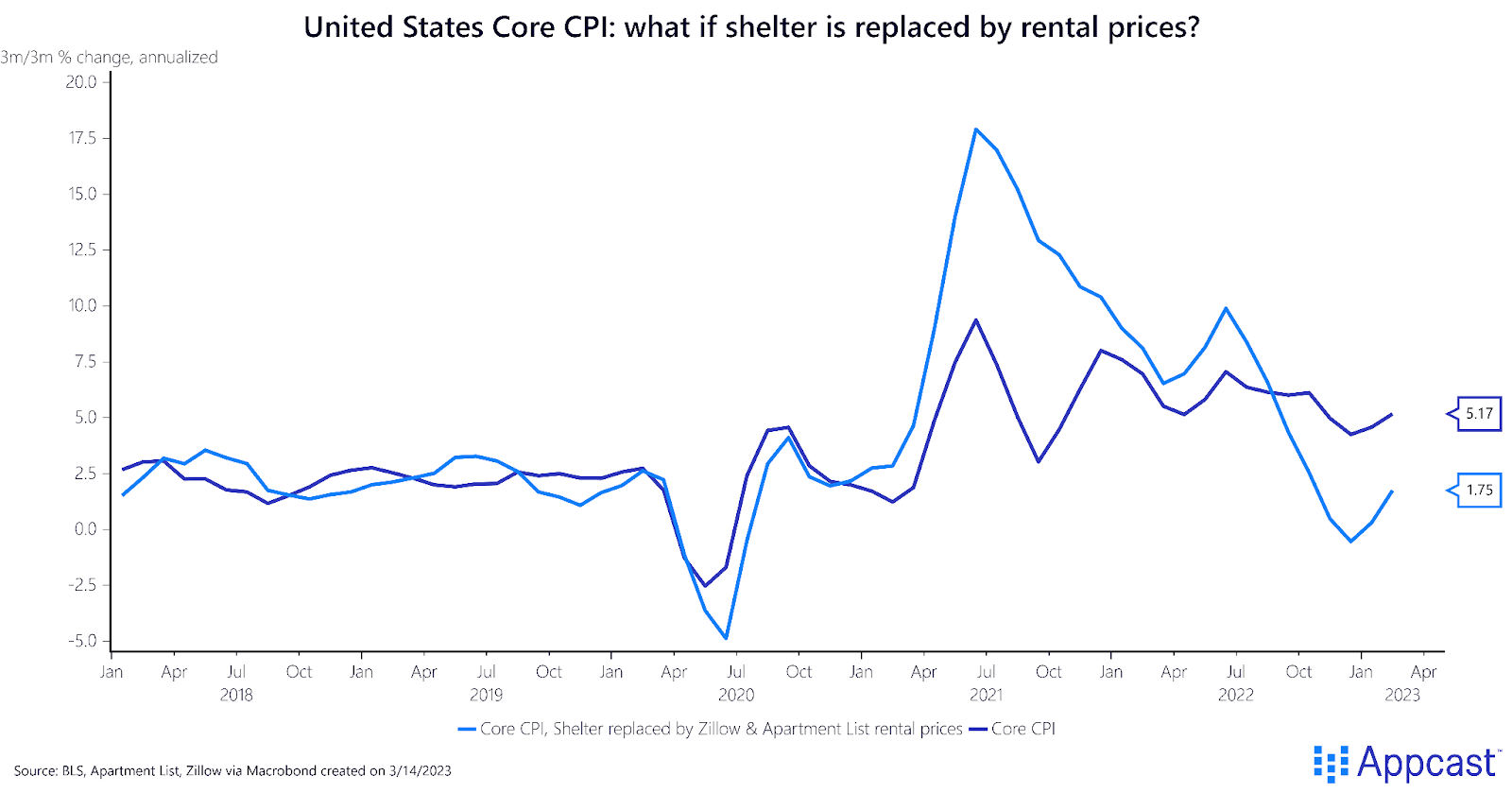

For housing, measures of market rents over the last year are pushing housing costs higher. However, if you look at current market rents from Zillow and Apartment List, housing price growth seems less dramatic. The CPI is lagged in a sense – it’s going to take many months for new leases to reset at these moderated levels. However, even when we add in these “real-time” measures of housing costs, core CPI trends are still worrisomely high. In layman’s terms, the light blue line in the chart below has moved higher and that factors in the new (lower) rents. So what’s driving inflation? The labor market, it seems.

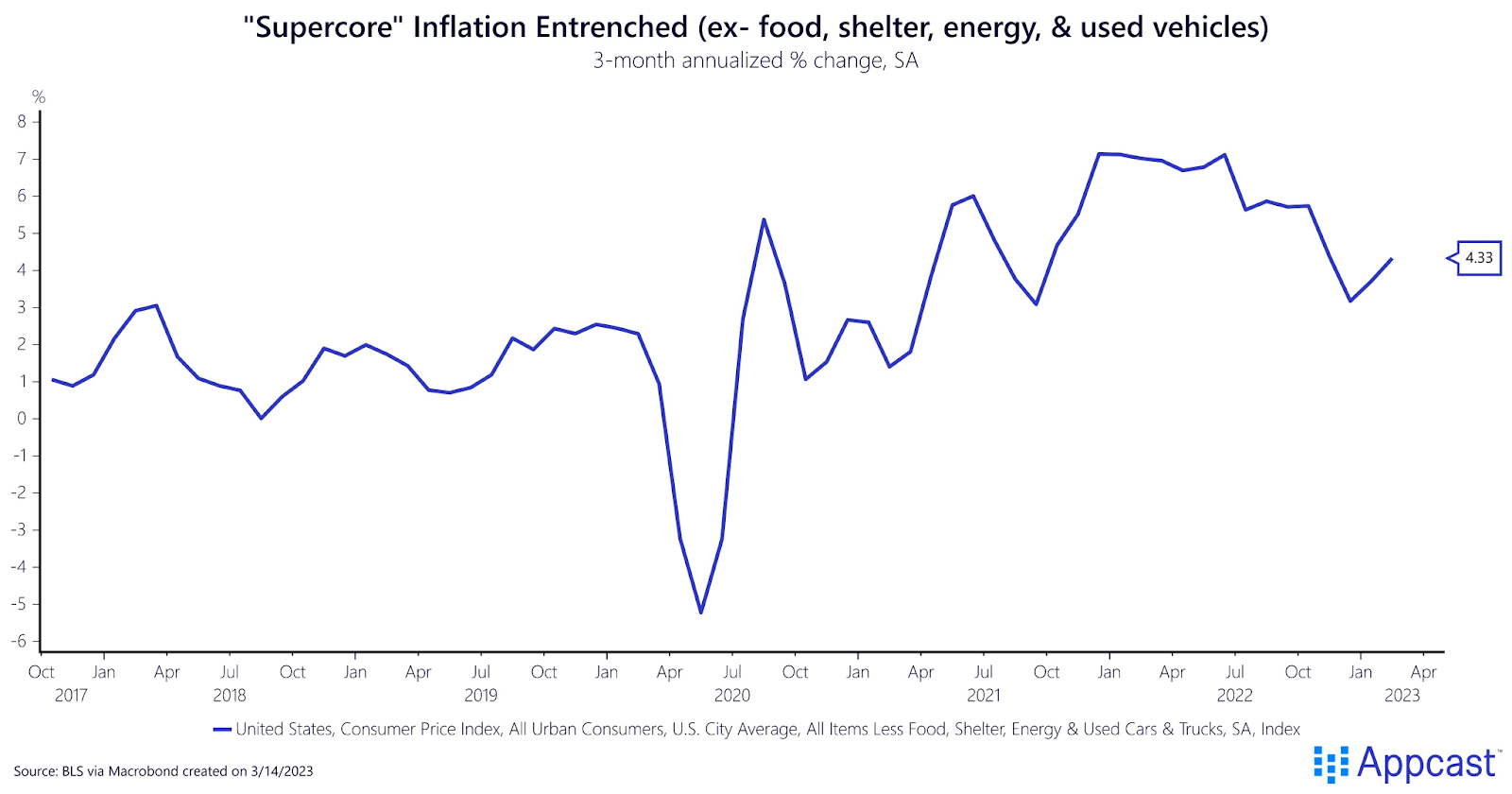

The second stubborn component of inflation is services. This is ultimately what Chair Jay Powell and the FOMC are paying the closest attention to. Services inflation, so the economic theory goes, is largely determined by the labor market. The “tighter” the labor market – the greater the imbalance of demand for workers oustripping the supply of workers – then the higher the wage growth. And, presumably, as wage growth remains elevated above historic levels, employers will attempt to pass on some of that new labor cost to consumers in the form of price increases.

Hence, the notion of “supercore” inflation – removing food, and energy, and shelter, and vehicles – to get at the services inflation trend. This “supercore” reading of inflation was also disappointing in February, rising 4.3% at an annual rate over the last three months. Assuming labor productivity growth of around 1.5%, and given current wage growth trends, this level of services inflation is not consistent with the Fed’s 2% inflation target and therefore fuels the widespread belief that the Fed has more work to do.

But, wait, wasn’t there just a series of bank failures? Aren’t markets tanking under the assumption that a financial crisis is brewing? All valid questions. That brings us to the Fed’s dilemma: alleviate financial distress or continue the battle against entrenched inflation. The Fed’s goals are often stated as a “dual mandate” – full employment and price stability. Well, we’re at full employment; but we certainly don’t have price stability. However, there is a lurking third mandate for the Fed: financial stability.

Over the last year, as interest rates have skyrocketed upward, there has been no major financial distress. Until now. So at its meeting next week, the FOMC is going to be forced to choose whether to continue to raise rates (in the quest to subdue services inflation back to its pre-COVID trend), or whether to hold off on further tightening financial conditions as the fallout from recent bank runs remains uncertain.

That is why markets are no longer pricing in a half-percentage point rise in short-term rates next week. Debate now centers on whether to raise rates at all. If the Fed blinks from the financial distress emerging and decides to hold rates where they are now, does it risk its credibility? I say “no,” as financial conditions are already tightening in wake of the SVB’s demise. Credit spreads are widening and stocks are falling; yet as interest rates have plummeted, that will feed through to an easing of financial conditions.

The Fed’s dilemma has huge consequences for the labor market. As we saw in February, the US labor market remains strong. While the recent inflation report is a bit discouraging, we knew it was going to be a bumpy road back to price stability. The downside risk to the economy of financial contagion, in the Fed’s eyes, likely outweighs the risk of a lower-than-necessary rate hike. So in a sense, the recent banking panic – assuming it doesn’t spread – will likely buy the labor market more room to run hot.