Quantitative Easing: What is it good for?

Central banks usually change interest rates to steer the economy. They increase the interest rate when the economy risks heating up and lower the rate during an economic downturn.

However, this policy no longer works when interest rates are stuck at zero. During the financial crisis of 2008 and the more recent COVID-19 recession central banks resorted to Quantitative Easing (QE for short) instead. QE is a fancy way of saying that central banks created money out of thin air to buy government bonds – and sometimes other financial assets – to stimulate the economy. During normal times this would only create inflation, but QE can actually help stimulate economic growth when the economy is significantly depressed.

How exactly can creating money out of thin air stimulate growth?

During a recession, the economy is usually operating below capacity because of insufficient demand. Central banks can stimulate demand by creating additional money. How? Money injections lead to higher asset prices, therefore creating a positive wealth effect. QE also lowers interest rates for mortgages, consumer, and business loans, which boosts household consumption and business investment. Milton Friedman argued back in the day that central bank cash injections – the proverbial helicopter drop of money – are even more effective.

During the COVID pandemic, many governments supported households and businesses with loans. The U.S. government sent out several rounds of stimulus checks while the Federal Reserve bought U.S. government bonds via QE. The combination of the two programs was effectively money-financed stimulus, which some economists had already suggested was needed after the financial crisis to stimulate growth.

QE only makes sense when interest rates are close to zero

A recent speech by European Central Bank governor Isabel Schnabel explains why money injections did not lead to inflation after the financial crisis, while they did during the COVID recovery. She argues that the effects of QE are highly state dependent, meaning that they will vary depending on the economic environment.

After the financial crisis, both firms and consumers were in a large deleveraging cycle, trying to pay down their debts. Central bank asset purchases did little to boost broader monetary aggregates (credit) and therefore inflation remained subdued.

During the COVID pandemic though, household and company balance sheets remained strong and even improved thanks to surging asset prices together with very generous fiscal support measures. Consequently, broader money and credit aggregates increased, which contributed to high inflation.

What are the risks of QE?

While the risks of QE were relatively benign during the anemic recovery after the financial crisis, we are now facing an economic environment of high inflation and high interest rates.

Those high interest rates have led to a substantial repricing of global bonds. Many central banks in advanced economies are now facing large paper losses because those government bonds were purchased at higher prices during the low interest rate years but have now fallen in value (bond prices are inversely related to interest rates).

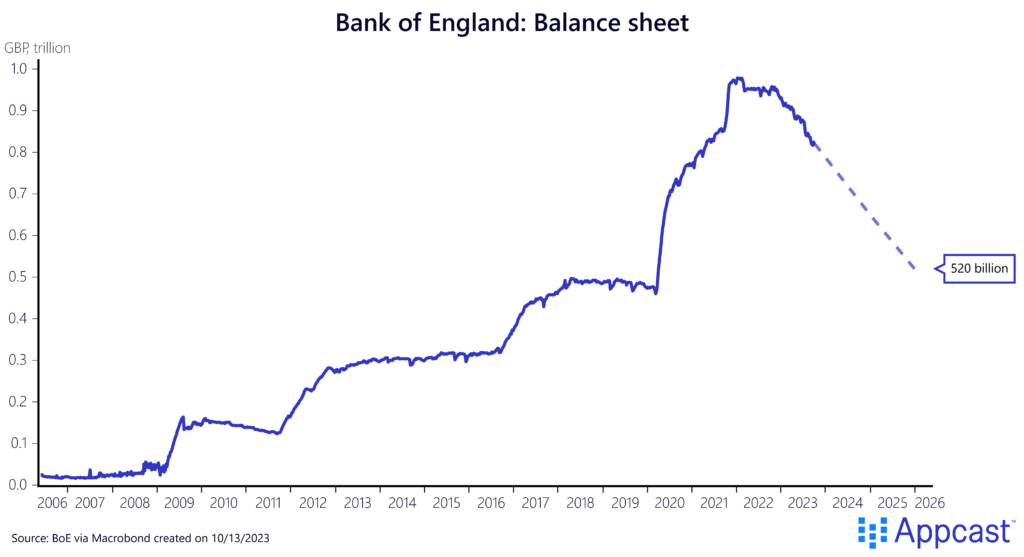

According to some estimates, the Bank of England will face a cumulative loss of more than a hundred billion pounds on its portfolio. These losses would not be realized if the central bank simply chose to keep the bonds on its balance sheet until maturity.

However, monetary policy makers at the BoE have recently decided to shrink the BoE’s balance sheet at an even faster pace. They want to sell up to 100 billion GBP in gilts (U.K. government bonds) each year until early 2026 to bring total assets down to 500 billion again.

That means the BoE will actually incur these losses if they sell gilts at a lower than purchase price. And more importantly, taxpayers will have to end up footing the bill: Just as the BoE transferred its profits from QE post-2008 to the Treasury, the U.K. government will have to subsidize any future losses.

Taxpayers might need to foot the bill

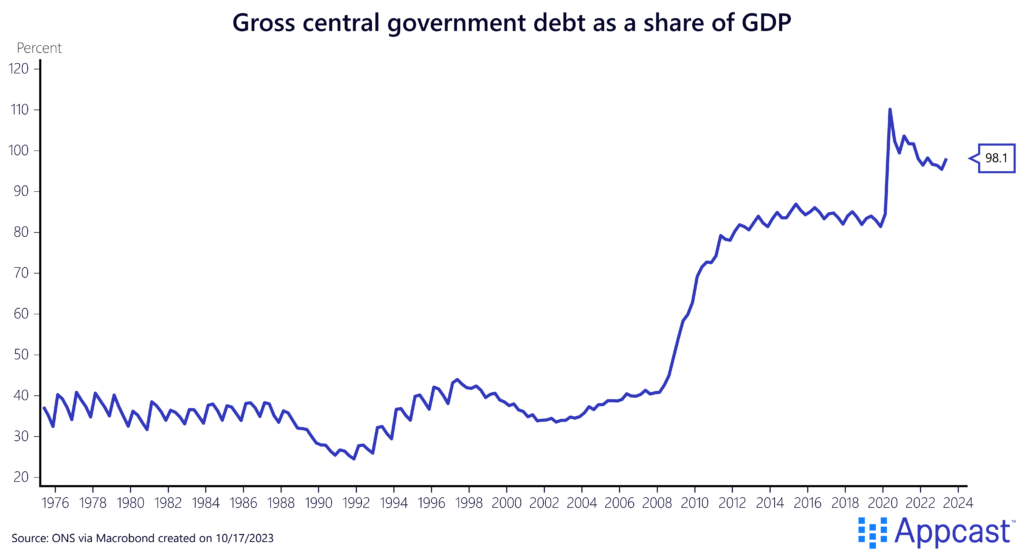

While estimates vary, it is plausible that the BoE cumulative loss from the recent asset purchases exceed 100 billion pounds. That would be a substantial blow to the U.K.’s fiscal position as the country is already struggling with its extremely high public debt level of about 100% of GDP together with a bleak fiscal outlook in the coming years.

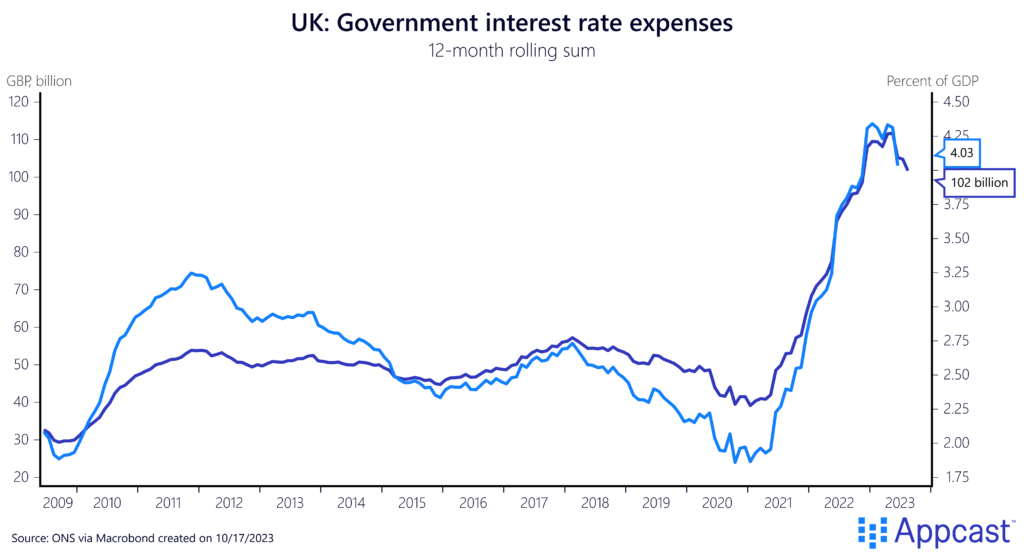

With the recent surge in interest rates, debt sustainability has become even more of an issue. The government’s interest rate expenses have surged from about 2% of GDP pre-pandemic to now more than 4% of GDP.

All of this begs the question why the BoE is engaging in Quantitaive Tightening (QT) – the sale of its bond portfolio. By its own admission, the effect on interest rates is actually minor. Selling the bonds in an orderly fashion will, according to officials, only increase rates marginally and will not disrupt the gilt market like what happened during the Liz Truss debacle last year.

Apparently, the only reason is to shrink the balance sheet to have more leeway when the next big crisis hits the U.K. economy. However, the size of the balance sheet should not be a constraint on future monetary policy. It therefore does not justify blowing a massive hole in the U.K.’s fiscal position right now.

The negative consequences for the UK economy and labor market

The negative effects from QT are well discussed and underappreciated. U.K. policy makers have been making a lot of blunders in recent decades. When interest rates were super low and debt-financed public investments would have been cheap, policy makers engaged in austerity instead, which damaged the economy for many years.

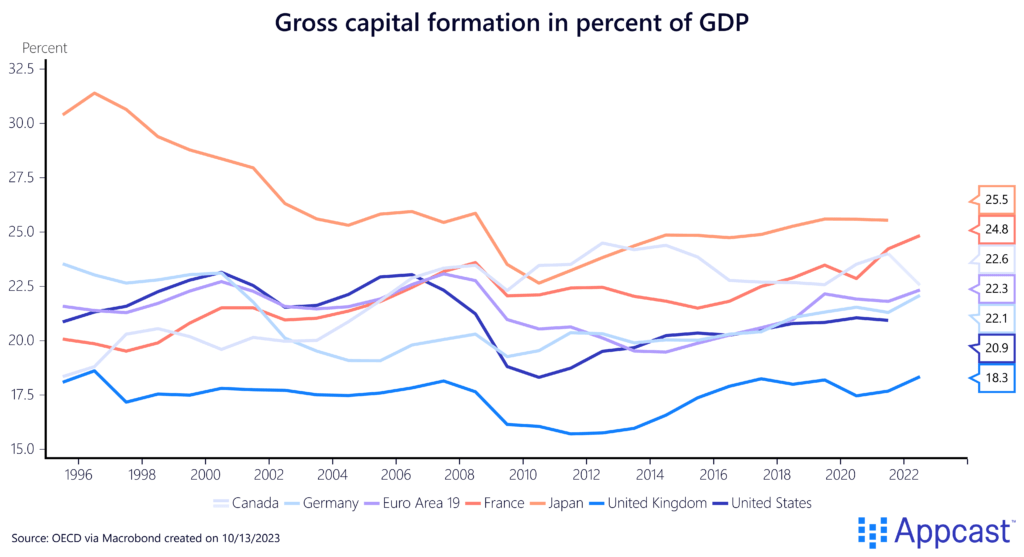

Now interest rates are rising, but the country is in desperate need of public infrastructure programs. The meager rate of gross capital formation in the U.K. in recent decades – a fancy way of saying how much money is invested in the economy – speaks volumes. Policy makers failed to take advantage of the low debt costs before COVID, and the country will now pay the price.

The BoE’s policy of shrinking the balance sheet will strain public finances even more. The additional money will have to come from somewhere, through a combination of higher taxes – most likely on labor income – and lower public spending, both of which will negatively affect the U.K.’s already poor growth prospects.

By the BoE’s own admission, QT does not have a substantial effect on current interest rates. However, it is going to blow a massive hole into public finances, which will negatively affect the U.K. economy in the years to come.

QT will most likely be a mistake and we will have to add it to the long list of public policy blunders in the UK.