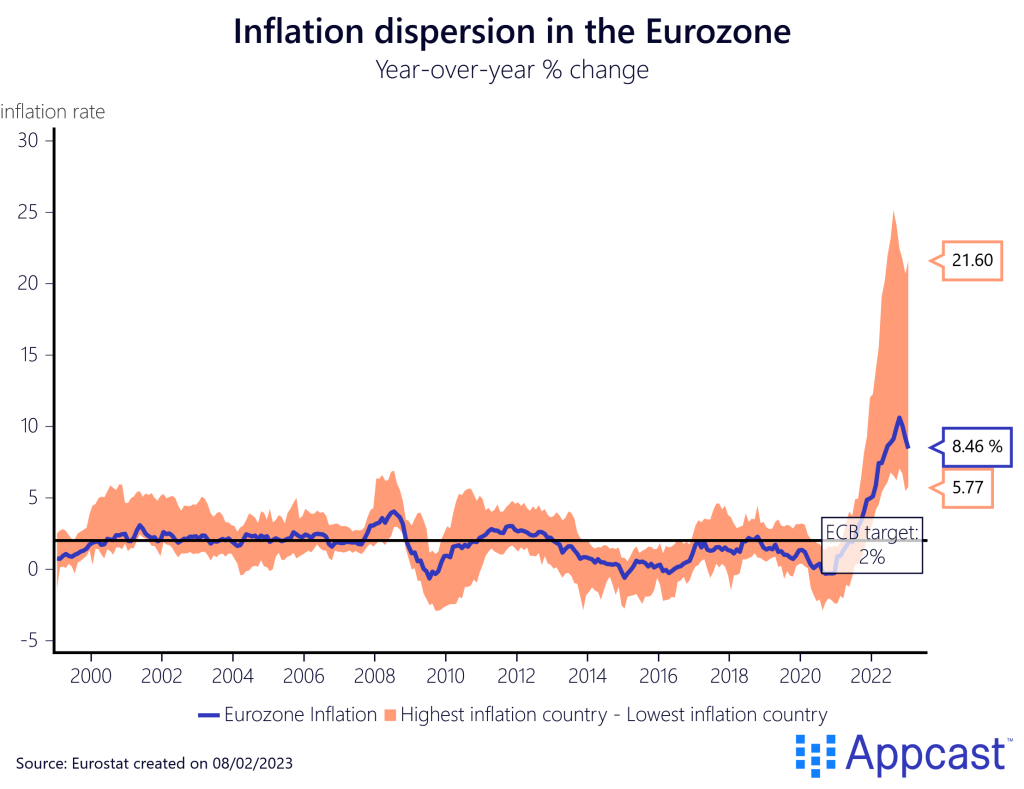

There is no doubt that the energy price shock resulting from the war in Ukraine has hit the European economy very hard. Many countries saw double-digit inflation rates, peaking at just over 10% at the end of last year. This is obviously a huge problem for the European Central Bank (ECB), which has a strict 2% inflation target.

After suffering from too soft demand and low inflation for an entire decade after the financial crisis, the economic situation in the Eurozone has now completely reversed: Inflation has surged across all sectors, some of it driven by the commodity price shock and some of it due to supply chain disruptions created in part by China’s zero-COVID strategy in 2022.

On top of that, governments and the ECB reacted with extreme stimulus packages when the COVID pandemic hit in 2020. Private sector balance sheets remained strong, and households were forced to reduce their spending during the economic lockdowns.

These forced savings have now been re-injected into the economy with a vengeance and have led to increased price pressures – especially for durable goods. This is precisely why the ECB started to tighten monetary policy last year and hiked the policy rate to above 2%. Some sectors are now suffering from too much demand, as ECB chief economist Philipp Lane recently argued.

Given the rapid rate hikes, most economists predicted that Germany would fall into a recession by Q4 of last year, for two key reasons.

First, after years of strong house price growth facilitated by low interest rates, the assumption was that the German housing market will suffer substantially once mortgage rates began to rise.

Second, Germany has a higher manufacturing share than most other European countries and has benefitted from cheap Russian energy for years.

Put those two together, and one can easily see why a German economic research institute has been forecasting a recession in the German economy.

Soft and hard economic data in conflict

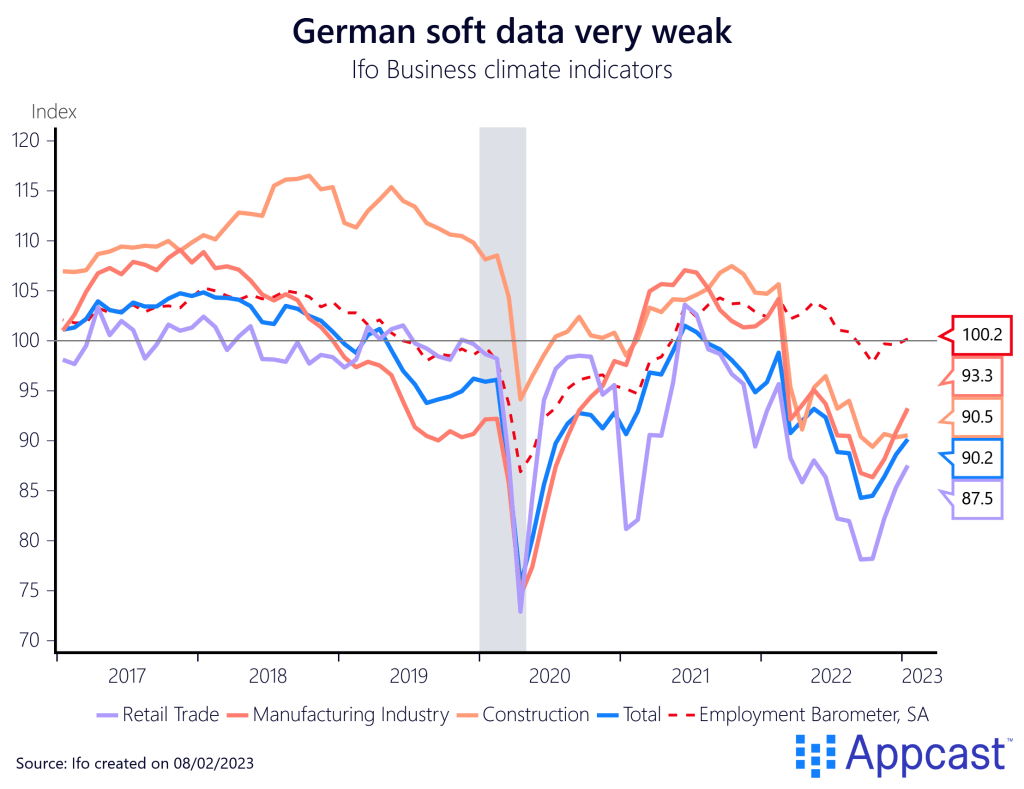

Soft economic data – economic and business surveys – seem to validate that the German economy is in a tough spot. Ifo, one of the largest economic institutes in Germany, publishes various business climate indicators that suggest unease in the private sector.

The Ifo employment barometer only slightly dipped below 100, suggesting that businesses’ willingness to hire new staff in Q1 of 2023 is still positive.

The business climate indicators, on the other hand, has been indicating a severe economic downturn, especially for manufacturing and construction.

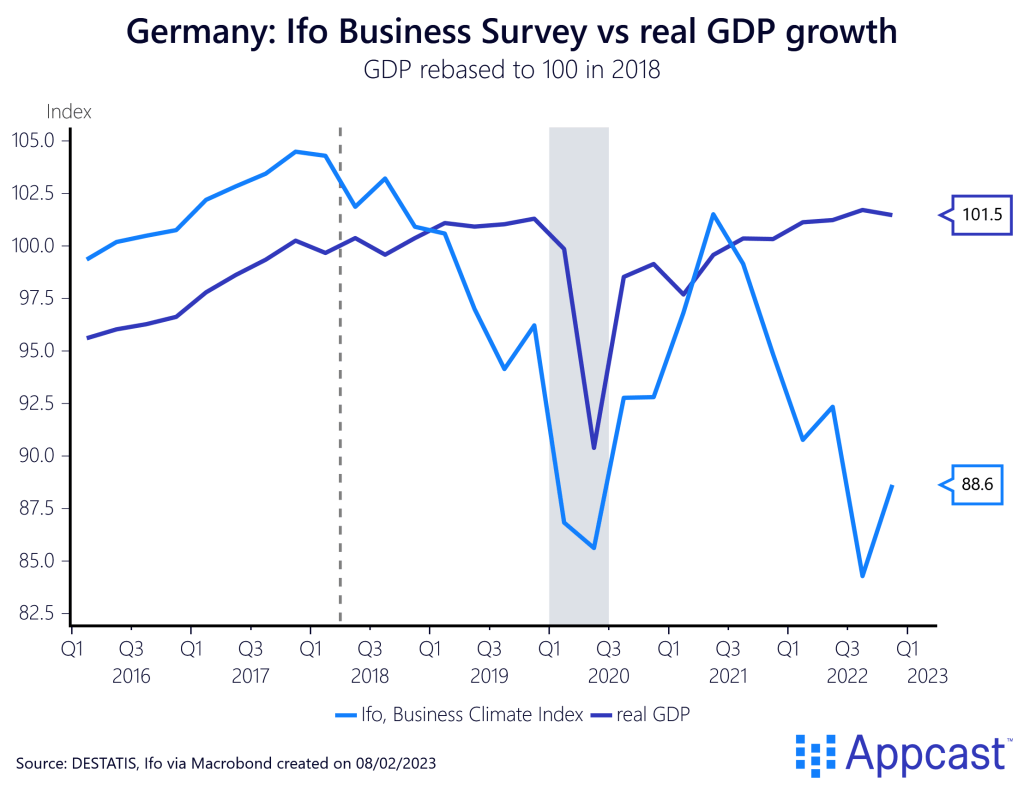

Somewhat surprisingly though, hard economic data does not corroborate the story of an economic downturn yet. The chart below displays the IFO business survey together with real GDP growth. While those two series usually track each other closely, we are currently seeing a record-wide gap.

While the Ifo index has plunged, GDP figures have been holding up quite well despite the massive commodity price shock from the war in Ukraine.

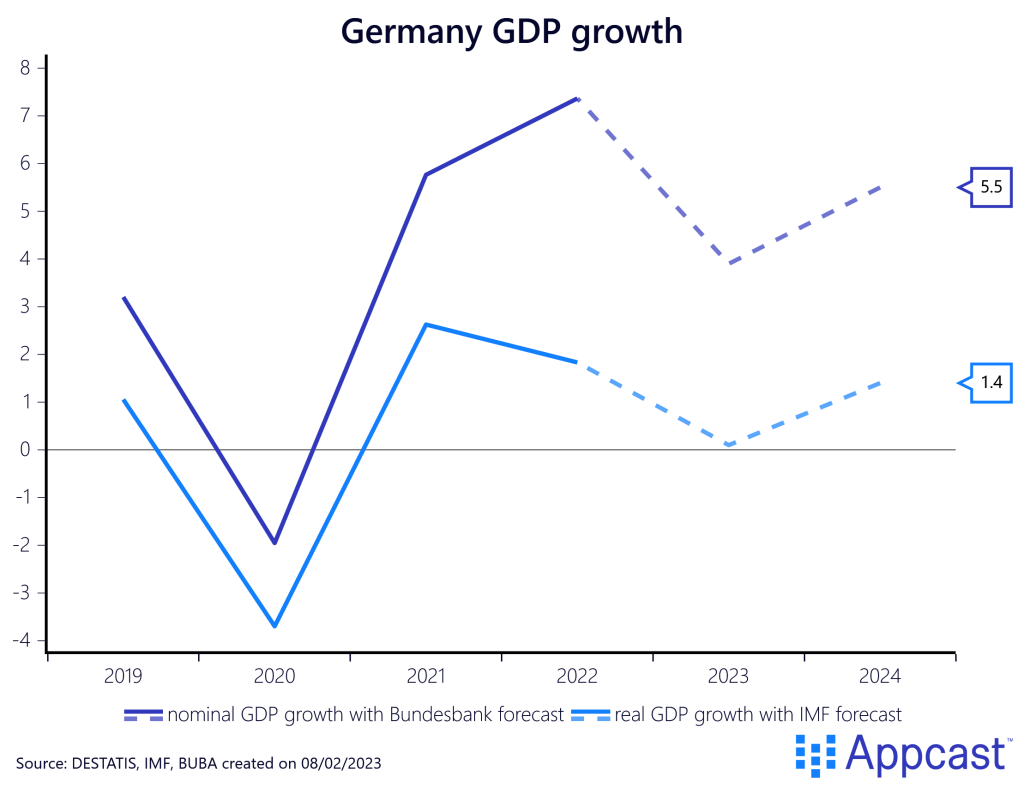

Nominal GDP increased by more than 7% and real GDP (adjusted for inflation) increased by 1.5% in 2022, numbers that exceeded expectations. Forecasts from the IMF have just been revised upwards in January. Instead of a mild contraction of -0.3% for 2023, the IMF is now forecasting 0.1% growth for Germany this year and 1.4% next year.

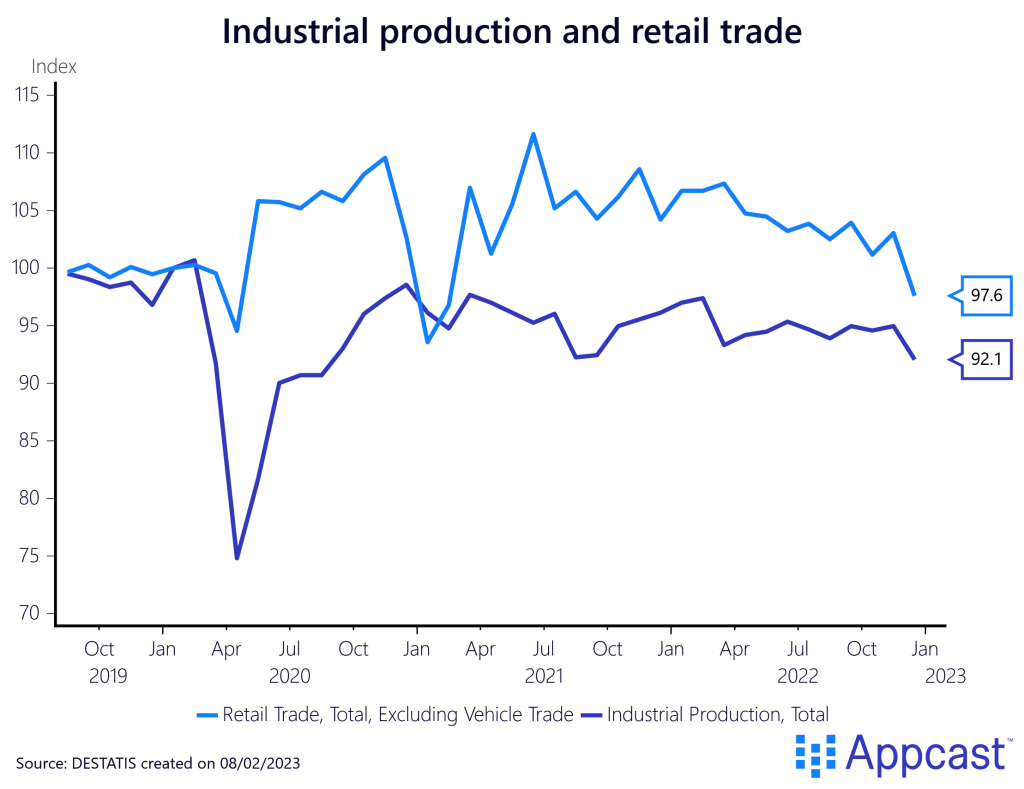

Especially surprising is that industrial production throughout 2022 has been doing alright despite Germany’s very high reliance on cheap energy imports.

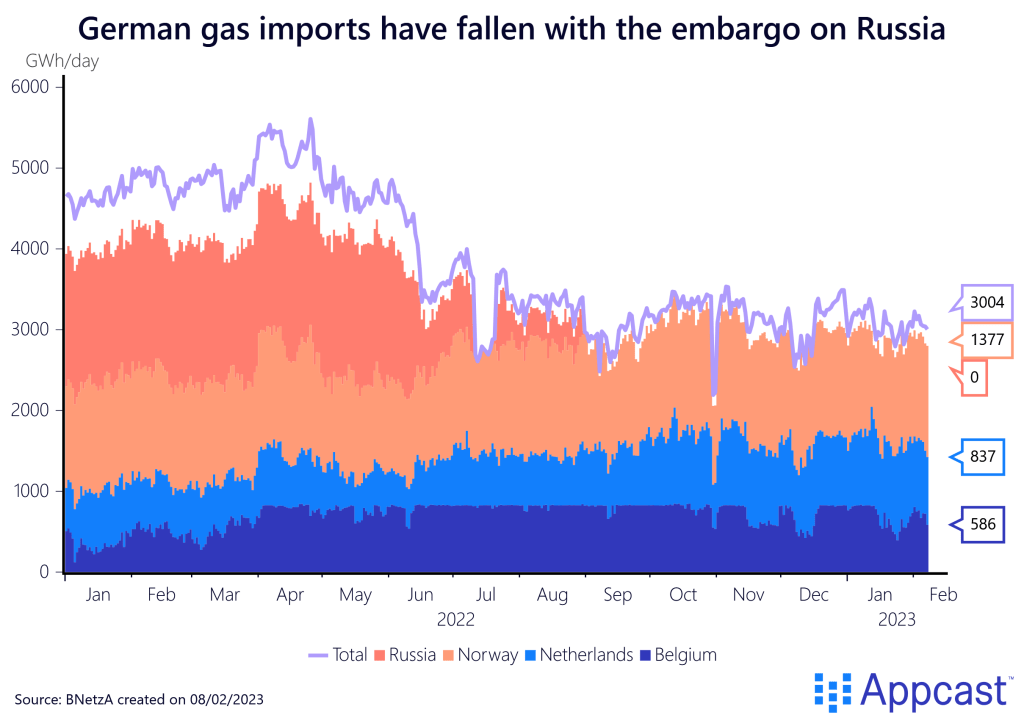

As one can see, gas imports have plunged since the beginning of Q2 with the sanctions imposed on Russia.

Industrial production is only slightly below pre-COVID levels in real terms and did not see a substantial decline last year. German companies adjusted and became more energy efficient during the energy crisis. According to a recent IFO survey, most industrial producers managed to save on energy without cutting production.

Retail trade did suddenly plunge last December but was generally pretty strong throughout 2022 compared to pre-pandemic levels. Domestic consumption also held up better than most forecasters expected, given the surge in energy prices.

As Scott Sumner recently discussed, most recessions in advanced economies are, in one way or the other, demand shocks. They might originate in the financial sector or be the result of bursting asset bubble with a subsequent painful deleveraging cycle that depresses spending. But, at their core, they are shocks to demand that weaken the economy.

Supply shocks usually tend to have smaller effects. While the massive energy price jump in 2022 led to an inflationary surge, it has not plunged Germany and the Eurozone into a recession yet, and most economic data surprised on the upside recently.

The IMF’s forecasted stagnation of near-zero growth this year is mild compared to the -5.7% decline Germany experienced during the Great Recession, giving you an idea of the relative importance of demand vs. supply shocks.

What’s the German labor market outlook?

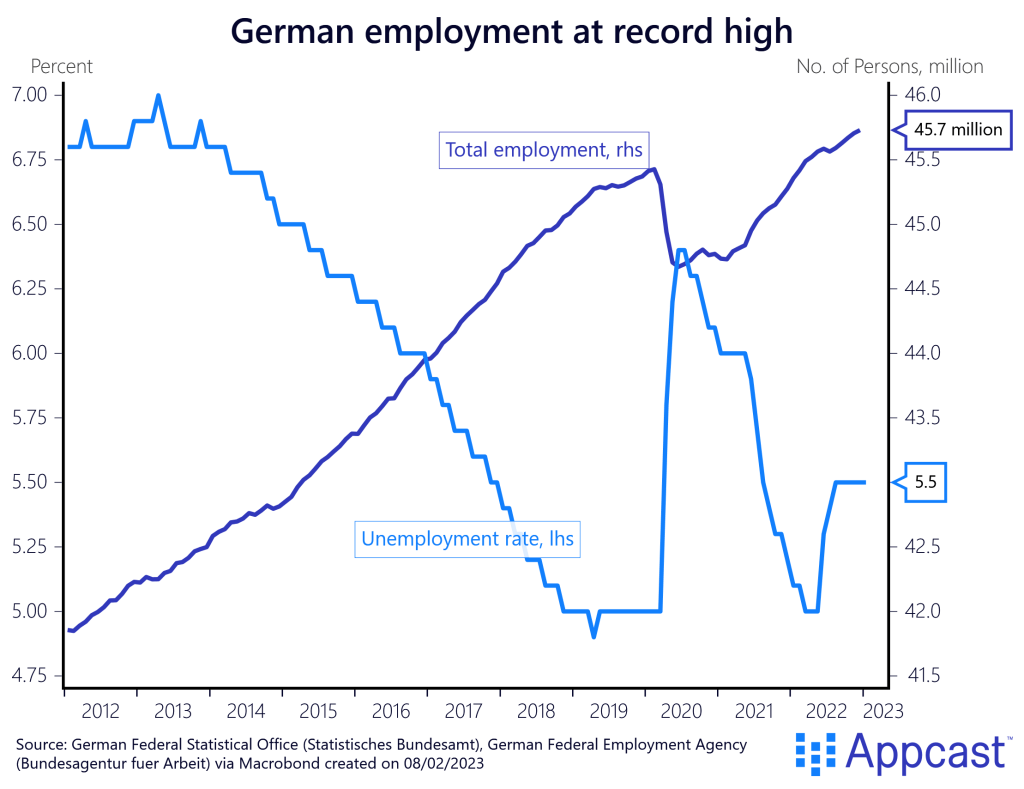

A mild economic downturn will have a very muted effect on the German labor market. The German unemployment rate increased slightly at the end of 2022 but remains at only 5.5%. This is significantly lower than at any time during the economic recovery in the aftermath of the financial crisis.

Rather than fearing layoffs, workers in Germany are actually in a strong bargaining position. The country is facing an acute shortage of skilled workers in various industries, a problem that will only get worse due to the country’s long-run demographic issues.

According to recent Stepstone research, Germany is one of the advanced economies that will be affected the most by adverse demographic trends with the working age population shrinking by more than 10% by 2040. And employers are concerned that automation will not be able to offset the missing workers.

For recruiters, this means that the life will certainly not get easier in the long run since German workers might soon realize that bargaining power is shifting back in their direction.

Conclusion:

Soft economic data has been suggesting a severe economic slowdown since last summer, but actual economic data surprised on the upside. The best bet is that Germany might only suffer a very mild recession in 2023 – or just a slowdown – despite the most severe energy crisis since the 1970s.

The labor market is holding up well, but going forward, the biggest problem for the country will be to deal with its long-run demographic decline.