Since economists already have trouble identifying recessions at the national level, knowing whether a state is in a downturn or not is even more tricky. The Philadelphia Fed has a measure that can help identify state business cycles.

What is a recession?

Contrary to conventional wisdom, a recession in the U.S. is not defined by two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth.

The NBER business cycle committee determines whether the U.S. economy is in a recession or not. They look at six different economic indicators that include two measures of employment growth, household income, personal consumption, retail sales, and industrial production.

While GDP contracted for two consecutive quarters in 2022, that might have been more a statistical anomaly rather than anything else. At the time, every NBER indicator showed that the U.S. economy was in an economic expansion.

What is the Sahm rule?

One big disadvantage of the NBER approach is that it cannot tell us whether the economy is in a recession right now. The Great Recession, for example, was declared one year after it actually began.

This is exactly why economists have devised models that can tell us where the economy stands right now. Nowcasting models are one example: Since GDP figures are only released with a significant lag, Nowcasts attempt to estimate GDP numbers in real-time.

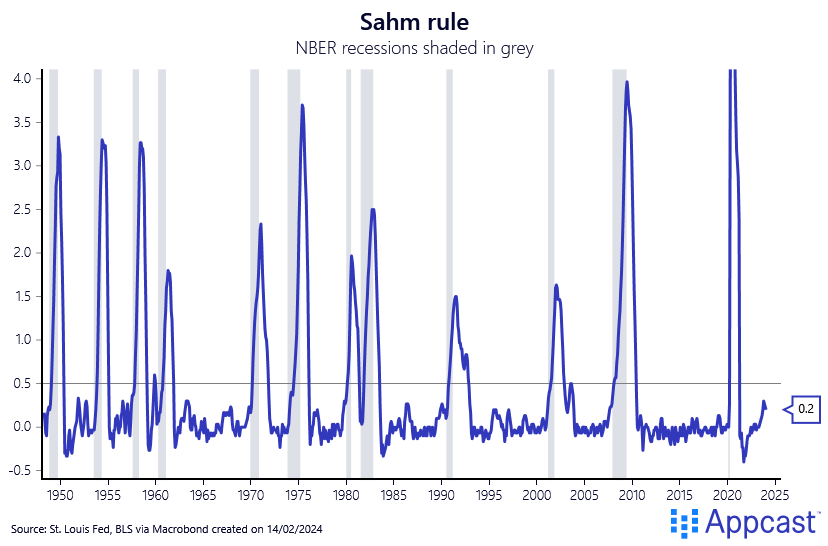

Another example is the Sahm rule, devised by former Fed economist Claudia Sahm. Her method tracks the unemployment rate. When the three-month moving average of the unemployment rate increases by more than 0.5 percentage points, the U.S. economy has typically fallen into a recession, as the rule stipulates.

As the chart below shows, the Sahm rule has correctly identified every single post-war recession in real-time (except the economic contraction during the spring of 2020 due to COVID-19).

State unemployment rates are more volatile

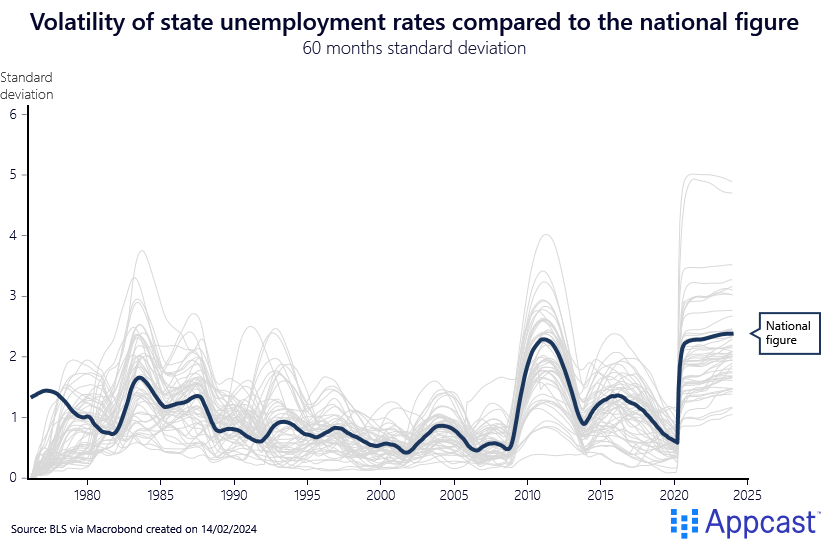

As the Sahm rule has become increasingly prominent, analysts have been calculating the rule for other countries and even U.S. states.

But, as Claudia Sahm recently pointed out, it is problematic to apply the rule to U.S. states because state unemployment rates are significantly more volatile than the national figure, as our chart shows.

The Philly Fed coincident index helps to identify local contractions

The Philadelphia Fed has devised an econometric model that can help identify whether a state is in a recession or not. They call it the State Coincident Index (SCI), which is based on the following monthly economic variables for each state: employment and unemployment, average hours worked in manufacturing, and wage and salary data (deflated by inflation).

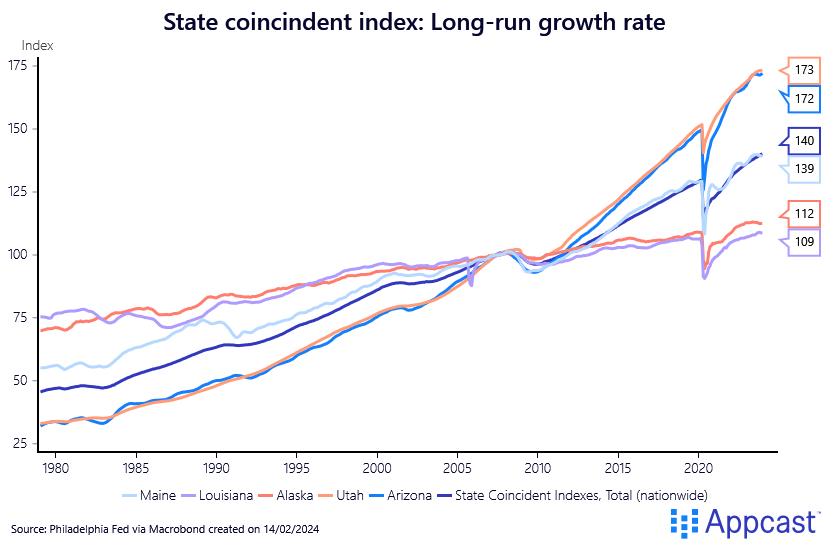

In the long run, the SCI is basically a measure of each state’s economic output. As one can see, U.S. states have very different underlying trend growth rates over time. These are mostly determined by long-run population dynamics, which are influenced by the state’s economic attractiveness for workers and businesses.

States with very high population growth like Utah and Arizona have grown much faster than the national average. Alaska and Louisiana have grown significantly slower. Maine has evolved quite similarly to the nation’s long-run growth rate since the year 2000.

Short-run fluctuations in the SCI are indicative of the regional business cycle. The state level index is more volatile than the national index because local factors like hurricanes, plant-level shutdowns, or changes in demand for one particular product or industry have a much bigger impact at the state level than for the national economy.

Researchers at the Philly Fed therefore define a state recession as a cumulative contraction of the SCI of at least 0.5 percent. Moreover, the peak to trough must be at least three months long.

States have different recession risks

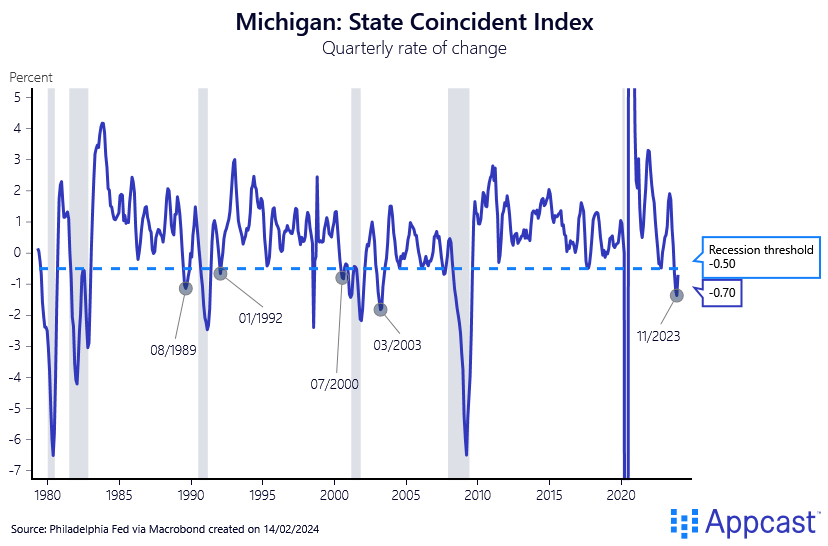

Michigan is a clear example of a state that has more recessions than the national average. The big three automakers have large production facilities in the state. Car manufacturing is a very cyclical industry that is also highly dependent on global demand. Vehicle production is significantly more volatile than other parts of GDP, which is why Michigan’s economic cycle is also more volatile than the rest of the country.

Using the definition for a state recession from above, one can see that Michigan has experienced several economic downturns that fell outside of national recessions: in the fall of 1989, in early 1992, in mid-2000, and in early 2003. Most importantly, Michigan is also experiencing a state-level economic contraction right now.

Which states in the U.S. are currently in a recession and what does that tell us?

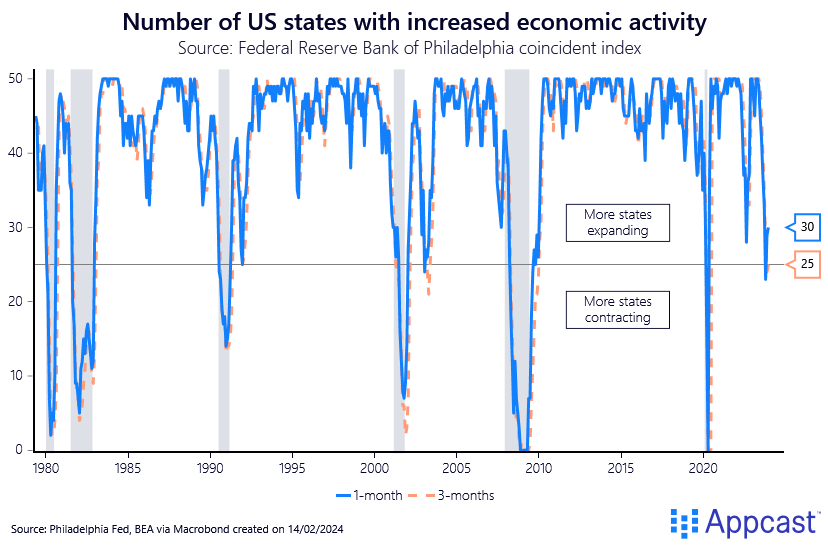

Just a few months ago, 27 U.S. states were recording negative growth when using the monthly rate of change of the state coincident index. That figure has now slightly recovered with only 20 out of the 50 states contracting.

An economy-wide recession becomes more likely if there are more states contracting at the same time. Not exactly surprising!

Historically, when more than half of U.S. states are recording negative growth, the probability that the entire U.S. economy will fall into recession a few months later rises significantly.

However, in both December 1991 and January 2003 the threshold was triggered, and the U.S. economy did not fall into recession thereafter. While directionally right, the rule therefore is not ironclad. As the number of states in contraction territory has recently declined again, it is safe to assume that the U.S. economy is out of the danger zone for now, as we have recently pointed out.

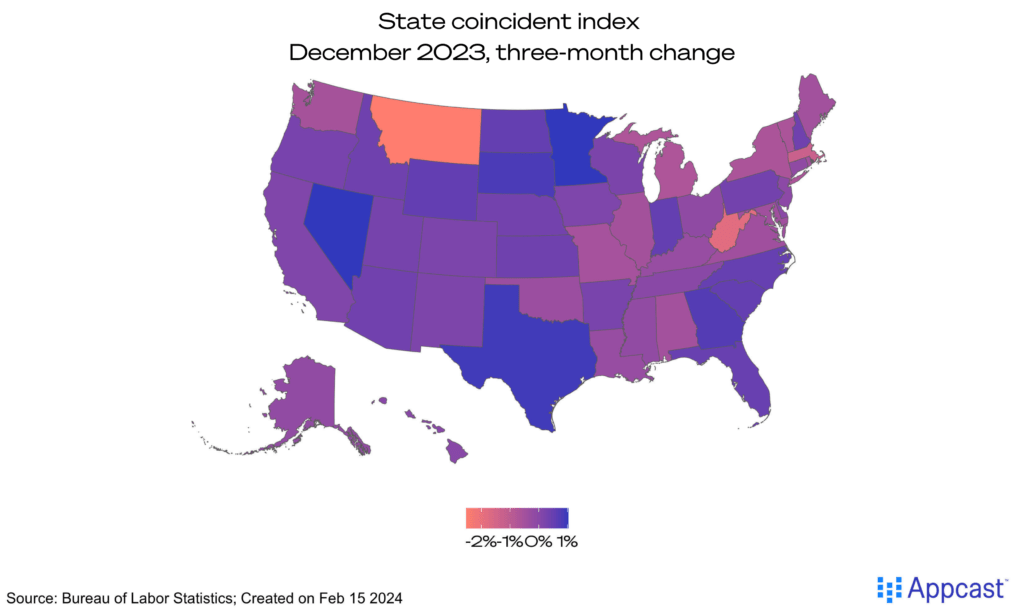

While there are quite a few states in the Midwest and Northeast that are recording negative growth, the amplitude of the contraction remains limited right now. There are only 9 states whose state coincident index has fallen by more than 0.5 percent over the last three months. And in that group, only New York and Washington state are among the top ten states by GDP while the other states are not large enough to have a sizable impact on national output.

What does that mean for recruiters?

While economists struggle to clearly define what a state recession exactly is, it is clear to everyone that regional economic activity can behave differently than the national economy. Individual states clearly have their unique business cycle dynamics distinct from the economy as a whole.

A national recession usually has a significant economic impact on every region within the U.S. – rarely are individual states immune from such a downturn. On the other hand, individual states can experience a labor market downturn even as the U.S. economy continues to perform well.

The Rust Belt states, for example, were suffering during the early 2000s from rapid deindustrialization even as the U.S. economy was doing reasonably well. Moreover, local job losses had a much more lasting impact on the regional labor market than economists initially expected.

Bad weather events like Hurricane Katrina can devastate local economies without having a severe impact on the economy at the national level. Closures of local plants can lead to massive reductions in workers’ salaries, increases in regional unemployment, and a loss of revenue for local government. Additionally, local suppliers can suffer from knock-on effects and might even go out of business, too.

It is a well-known truth that the labor market is not really one single market. It is split up into many different regional markets, and then divided again by sector. Recruiters therefore need to be aware of not just national but also regional economic factors and labor market trends when making hiring decisions.