The wrong culprit

Over the last two years as inflation has surged, big business has been blamed for jacking up prices amidst a cost-of-living crisis. Corporate greed was identified as one of the big drivers of inflation in this economic cycle. Even in some academic circles, corporate profits were said to be driving inflation in 2022. The IMF and the ECB more recently have suggested that corporate profits are playing a part in the inflation story.

In what follows, I will show that this argument is built on very shaky foundations and that the story about corporate greed gets some of the basics wrong. In fact, more recent data for the U.K. suggests that corporate profit margins decreased. Moreover, the labor share, the part of GDP that goes to workers in the form of wages, has also remained stable, suggesting that, in aggregate, corporate profits have not increased at the expense of salaries.

While the story for the Eurozone is a little bit more nuanced, workers there have also been able to make up for lost income in the form of higher wages more recently. And the same is broadly true for the U.S.

Economic theory suggests that wages are sticker than prices

Let’s start with a little bit of economic theory. Generally speaking, wages are stickier than goods prices in the short run. So, if policy makers try to boost the economy, let’s say by increasing the money supply substantially or sending out stimulus checks, then what will happen is that prices will increase before wages do.

And this means that, following this positive demand shock, inflation will first be driven by the increase in goods prices, and as a second-order effect by the increase in wages. But the underlying cause of inflation was the injection of money, not the increase in goods prices, nor the later increase in wages as workers attempt to gain back some of their lost purchasing power.

U.K. profitability is slightly down

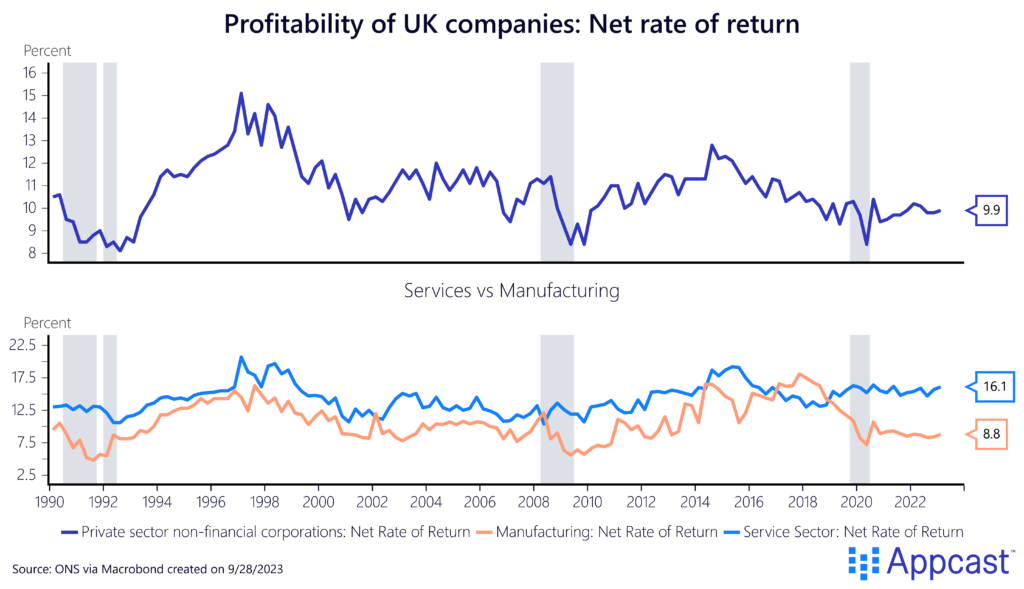

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) in the U.K. is collecting data on the net rate of return – a measure of profitability – for the entire corporate sector and different subsectors. What the data shows is that profitability of the U.K. business sector did not increase at all during the pandemic.

While profitability of the service sector ticked up slightly, profitability for manufacturing actually declined, thus leaving the aggregate measure unchanged.

Profit and labor shares show no clear trend

Another way of looking at changes in the distribution of income between workers and capital owners is to look at the labor share.

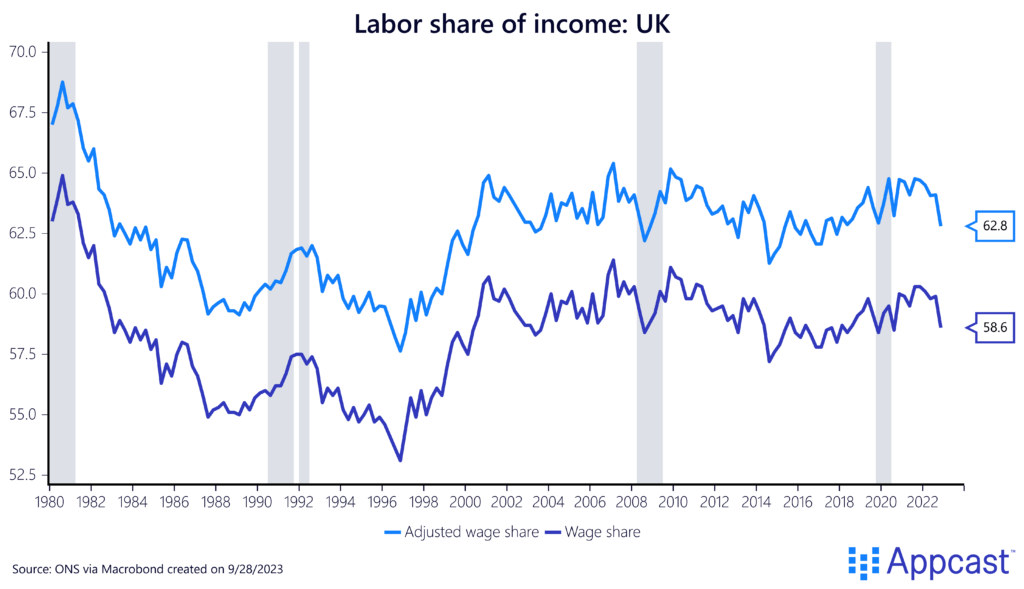

While the U.K. labor share dropped by more than one percentage point over the last year, it had previously increased during the pandemic. And the current value is still higher than it was during the mid-2010s, the 1980s, or the early 1990s. There is little to suggest that the labor share has fallen because of a rising profit share in the economy.

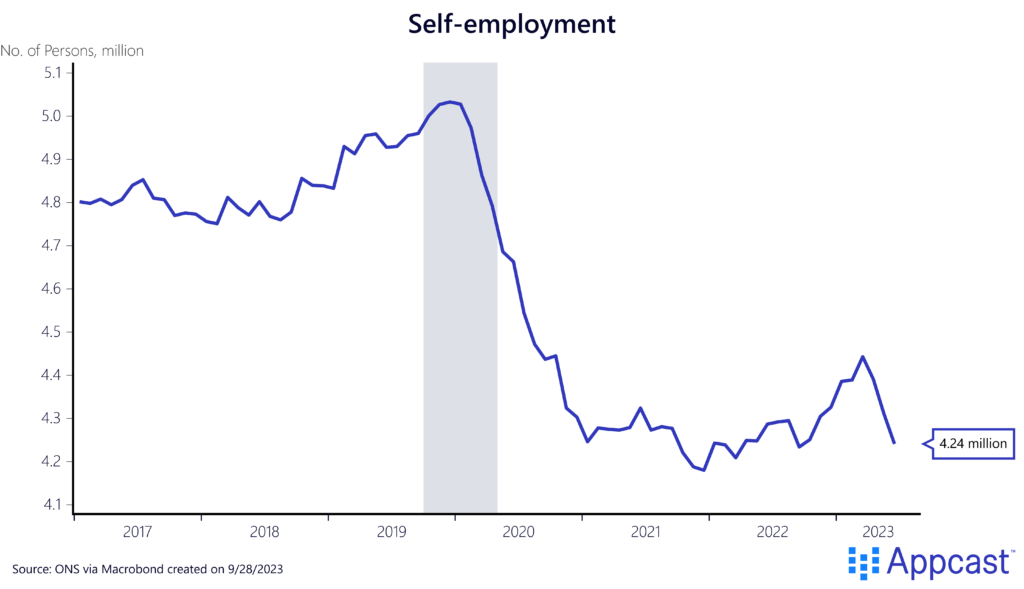

One big disadvantage of the time series above is that is does not account for the labor income of the self-employed. The income of self-employed workers is classified as “mixed income” in the national accounts. Conceptually, it is very difficult to distinguish between capital and labor income for a self-employed worker. One simple adjustment method is to assume that about two thirds of the income of the self-employed is labor income (roughly the same proportion as for the economy as a whole). I have used that method to calculate an adjusted labor share series that takes income from self-employment into account. As one can see, both series basically follow similar patterns.

Even as the number of self-employed in the U.K. has plummeted, mixed income from self-employment has not. Our best guess is that many of the self-employed that dropped out of the labor force during the pandemic simply generated extremely little income from their activity.

Similar story for the U.S. and Eurozone

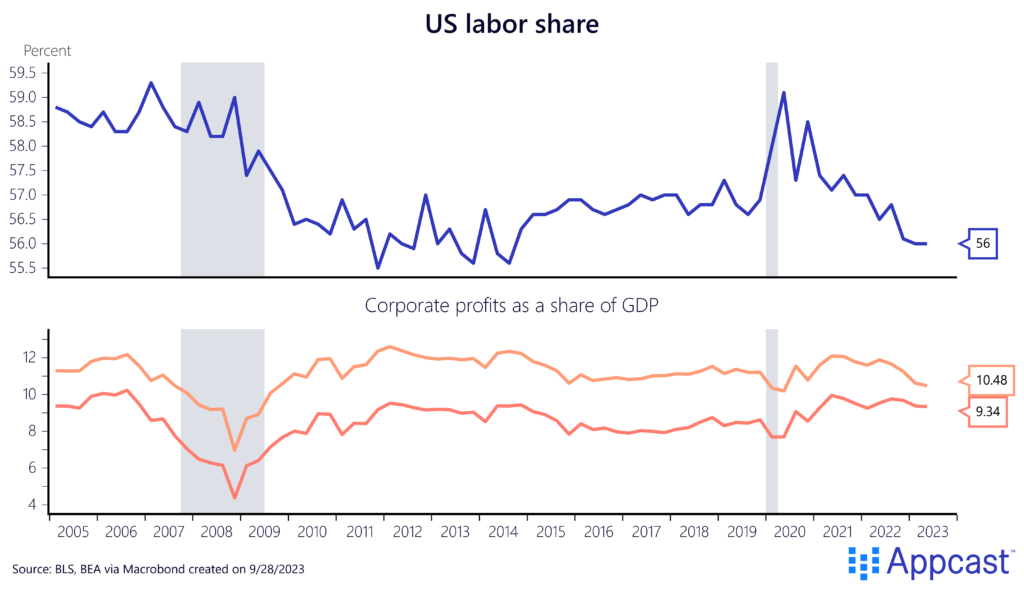

When looking at the U.S. and Eurozone data for labor income and profit shares, a similar pattern emerges. The U.S. labor share surged during the first two years of the pandemic, thanks to very generous income support measures from the government such as stimulus checks.

While corporate profits increased during the first two years of the pandemic, they have recently fallen again. Two factors have an unusually large impact on the U.S. profit share. First, the country receives more profits from abroad than it pays. Two, the Federal Reserve’s unusually large balance sheet is currently distorting profit measures in the national accounts.

Adjusting for those two factors does not fundamentally change the picture though. While rising slightly at the outbreak of the pandemic, profits as a share of GDP are currently not unusually high.

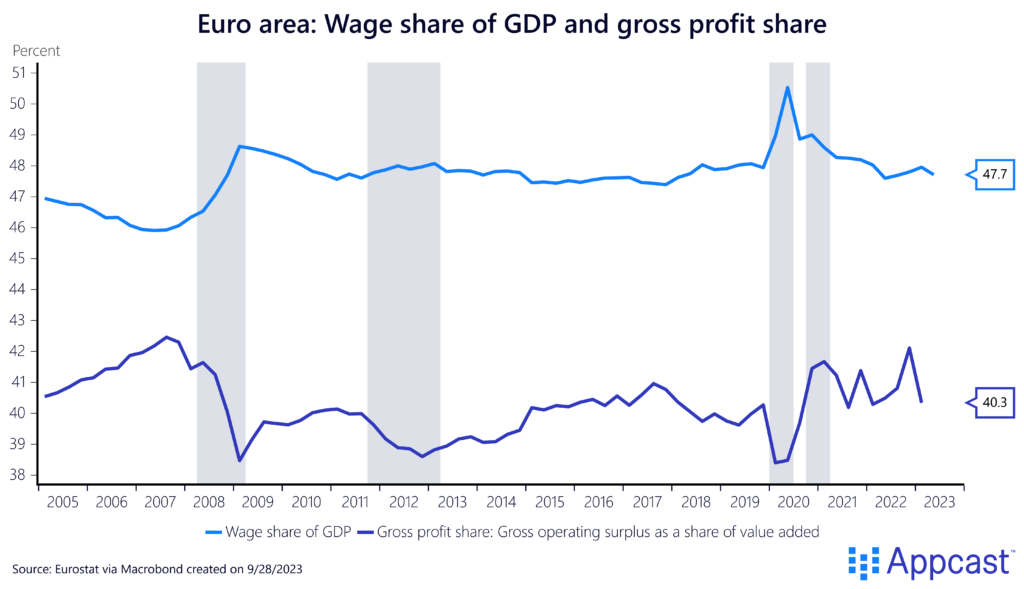

The labor share for the Eurozone surged early on during the pandemic before falling back down. Gross profits – measured as a share of value added – for the Eurozone show the largest temporary increase in 2021 and 2022. The latest data point though shows a decline back to pre-pandemic levels.

So, what are the factors that explain inflation?

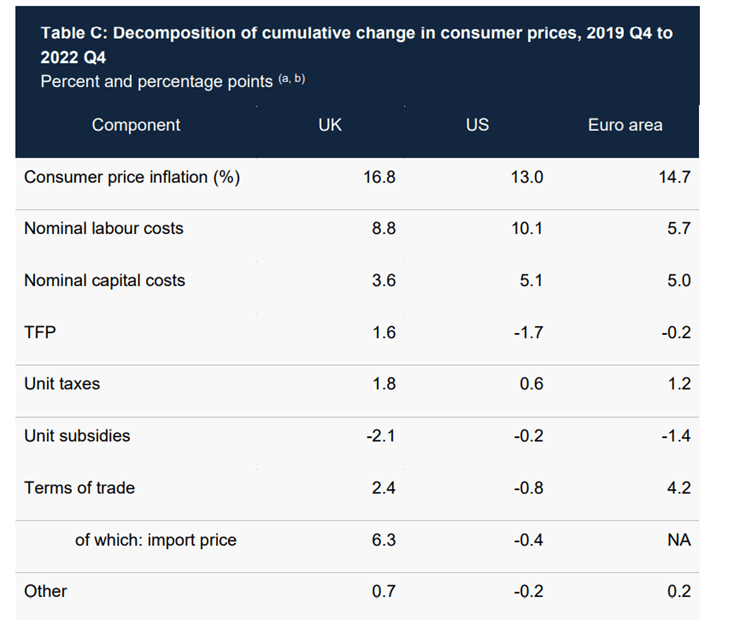

While the charts above do not exactly prove or disprove causality, more rigorous research from the Bank of England (BoE) also disputes the fact that rising profit margins contributed to the inflationary surge.

If corporate greed did not contribute to inflation, then what did? Generally speaking, there are three main factors that have substantially pushed up the inflation rate across advanced economies:

- Large direct fiscal support measures for housholds combined with increases in broader money aggregates, stimulating economy-wide nominal demand

- Extremely tight labor markets that have pushed up wage growth and increased the pass-through from inflation expectations to wages

- Supply side factors like the global supply chain crisis and surging commodity prices

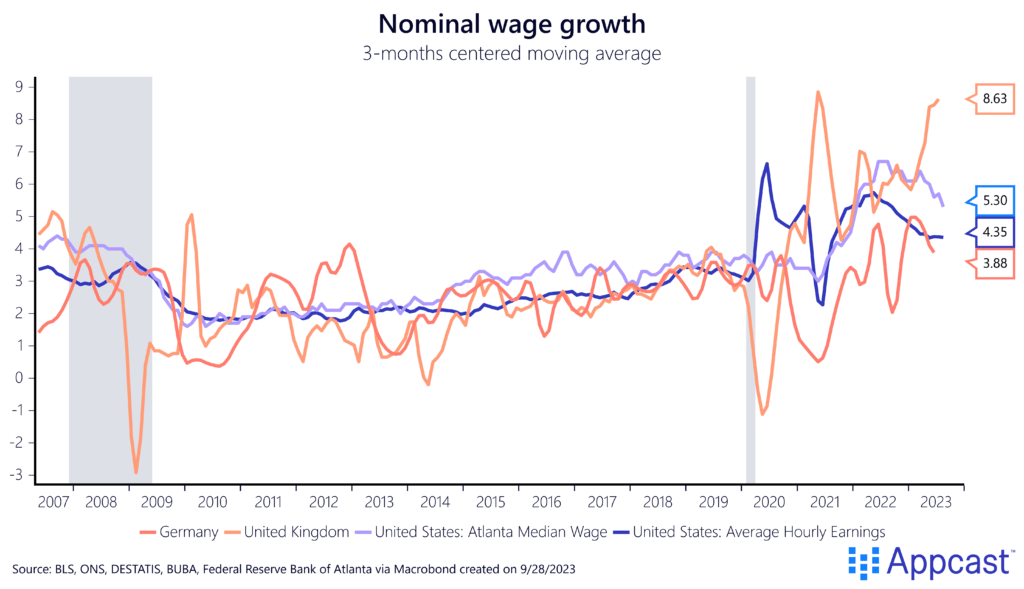

The BoE conducted an extremely insightful composition exercise that broke down the increase in inflation into several subcomponents. Their study shows that wage gains are a big part of the inflation story, especially in the U.S. and U.K. Again, this does not mean that they were the ultimate cause of the inflation shock but that their contribution was quite significant.

For the U.K. and Eurozone, the terms of trade shock – higher import prices – were also a big factor. This was mostly the result of the surge in energy prices. The U.S., being a big energy producer, was less affected.

Thirdly, nominal capital costs have played a relatively large part for the Eurozone and the U.S. This does not necessarily mean that the profit share went up. That measure also includes income of the self-employed, rental income from housing, depreciation of assets, and so on.

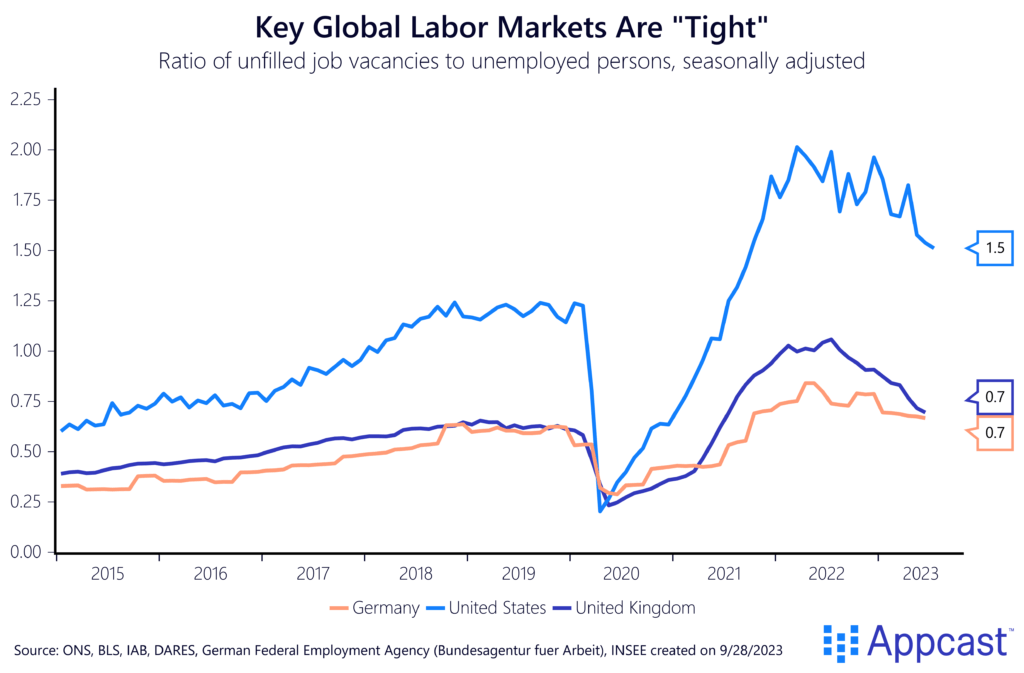

There is no doubt that the labor market tightness that advanced economies have seen since the pandemic has been one big factor pushing up inflation. The number of unfilled vacancies to unemployed workers surged to record highs. Poaching became more common as the pool of idle workers on the sideline shrank and job switchers also larger wage gains.

The increase in the bargaining power of workers also pushed up aggregate wage growth to levels not seen in decades, which contributed to the general rise in prices.

Conclusion

Just as we shouldn’t blame corporations for hiking prices, workers also should not be blamed for demanding higher salaries when labor market conditions turn in their favor.

Some of the labor market tightness can ultimately be explained by policy makers’ actions, stimulating the economy above “potential output.” Excessive labor market tightness is a side effect of too high aggregate demand relative to the economy’s capacity to produce real goods and services. And that was the ultimate cause of the inflationary surge.