Revisions smack down job growth

The U.S. economy might have created some 800,000 fewer jobs last year than what we initially thought. This is obviously a big deal, even in a labor market that employs more than 155 million people. We will provide some context on this recent data revision and the current trajectory for the U.S. labor market.

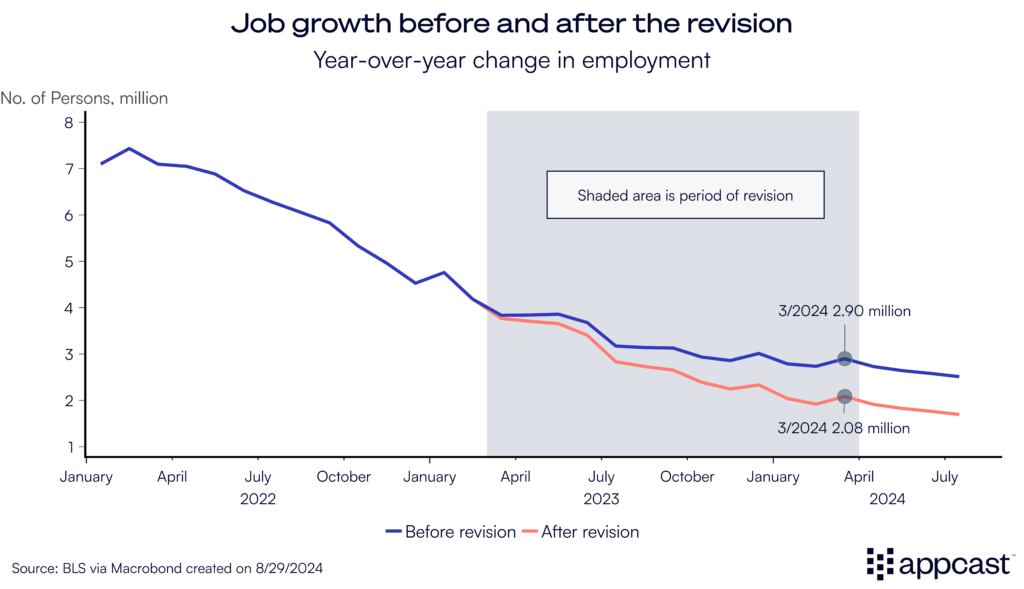

Let’s start with the facts. Before last Wednesday, numbers from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) suggested very strong employment growth of about 2.9 million during the year from April 2023 throughout March 2024. Following the data revision that occurred on August 21, the BLS now thinks that only 2.1 million payroll jobs were created during that year, about 800,000 fewer jobs.

This has brought monthly job growth down from an outstanding 242,000 jobs to a decent 174,000 monthly jobs created during that period.

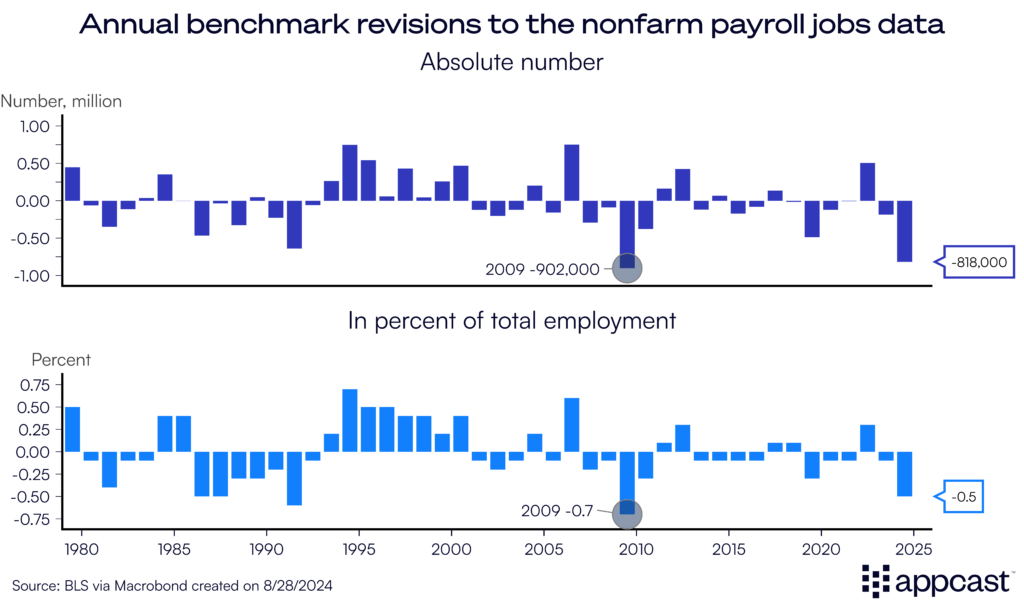

The downward revision has also been one of the largest in recent history, other than the benchmark revision for the recession year of 2009!

This is true both in absolute terms as well as in percentage terms. The 800,000 jobs lost have shaved off some 0.5% of total nonfarm payroll employment.

Why did this revision happen?

Data revisions happen all the time. A lot of economic data, especially labor market data, is measured with some inaccuracy, and later data points often improve the precision of prior readings.

While some people have quickly cried wolf and spread conspiracy theories that the BLS has juiced up job numbers to help the Democrats in an election year, this is obviously nonsense! First of all, this was a scheduled data revision that happens annually. Second, it doesn’t really make much sense that the government would admit some four months prior to the election that job growth is much slower.

Remember that the BLS cannot count every single job in the economy. That would be an impossible task in a labor market of more than 155 million. Instead, it gathers data from surveying approximately 119,000 businesses, covering about 629,000 worksites. The data from this survey, called the Current Employment Statistics (CES) or payroll survey, is used to estimate monthly and yearly payroll job growth.

One important adjustment that the BLS needs to make to calculate employment figures is to account for companies that go out of business, and for companies that are being newly created. But some economists currently think that the method the BLS currently uses to do so, the “birth-death model”, has been out of whack since the pandemic.

The economy has obviously undergone some seismic shifts since COVID-19 first spread around the globe. The pandemic and subsequent macroeconomic shocks have severely distorted economic patterns, including in the labor market, thus creating all sorts of problems for statistical agencies that rely on models using historical data. After all, we have seen some very extreme data points in recent years, starting with record high vacancies, a low unemployment rate combined with record high participation rate, and a record number of new businesses being created.

Some economists have argued that these large macroeconomic shifts have led to an overstatement of job growth throughout 2023 to 2024 because the BLS adjustment for the “birth-death effect” has been off. It remains to be seen whether this problem will persist throughout this year.

Record high migration continues to distort the data

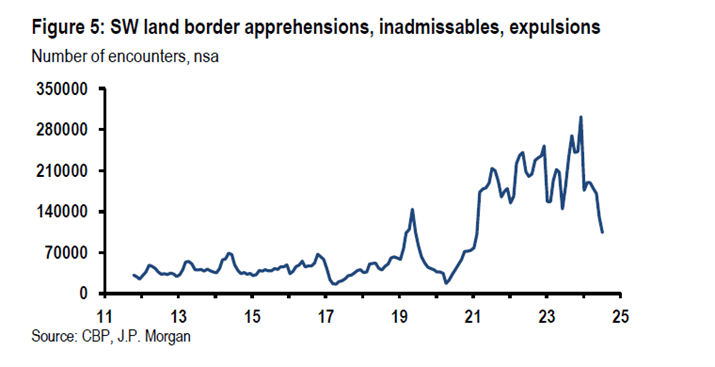

The massive boost in immigration the U.S. has experienced since late 2022 continues to affect the labor market data. The BLS measures employment using two different surveys, the household survey and the payroll survey. While these capture slightly different concepts of employment, they usually move in a similar direction. Since 2022, however, the two employment measures have massively diverged with employment based on the household survey stagnating while payroll employment has continued to do well.

As we previously explained, the most likely explanation is the massive surge in net migration, particularly illegal migrants. Undocumented workers are unlikely to be captured in the household survey due to fear of exposure or deportation

The payroll survey (CES), on the other hand, only asks for the total count of employees and not for employee-level information, which is why even undocumented workers are likely to be captured in the jobs report.

Even the recent benchmark revision released last week could be undercounting some workers. The benchmark data is part of the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW), which relies on data from state unemployment insurance agencies. Employers are responsible for registering their employees, which involves submitting information such as the employee’s name and social security number. The QCEW therefore counts all employees for whom employers are paying unemployment insurance taxes.

But because undocumented migration has been unusually high in recent years, the QCEW is most likely undercounting employment growth, too. That is because some employers may simply pay undocumented migrants “off the books.”

That means that the benchmark revision of minus 800,000 jobs throughout the year to March 2024 was probably too large since it is undercounting the true number of payroll jobs. Goldman Sachs, for example, believes the true size of the downward revision should only have been 300,000, a monthly loss of 25,000 jobs throughout that period, instead of 70,000!

Even so, there is absolutely no doubt that the U.S. labor market has been cooling over the last year. The Federal Reserve now believes that the labor market is much closer to being balanced and that a first rate cut in September is required since monetary policy is now slowing down economic activity.

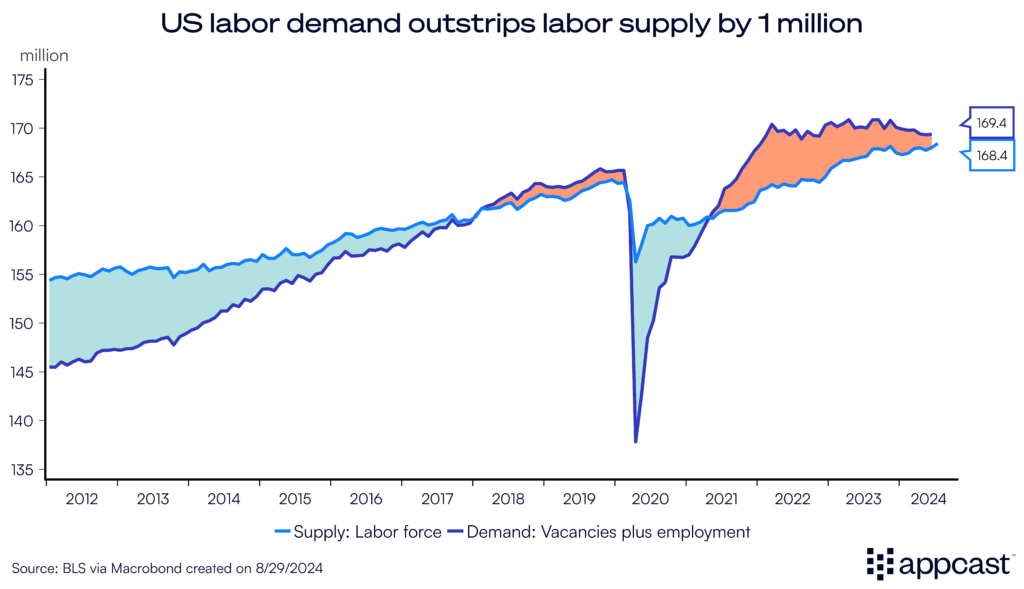

Our measure of tightness shows that the gap between labor demand and labor supply has been shrinking for about two years. Labor demand now exceeds supply by a little over a million, compared to about five million in 2022.

What does that mean for recruiters?

The big downward revision of 800,000 jobs to U.S. employment made a lot of headlines. While the number sounds terrifyingly large, it represents “only” about 0.5% of all jobs in the United States. It brought down monthly job growth from April 2023 to March 2024 from a strong pace of 240,000 jobs to a mere decent 170,000 jobs. And a lot of economists believe that the size of the revision was exaggerated because of jobs being done by undocumented workers. Recruiters therefore do not need to worry that the U.S. labor market is not growing anymore. The economy is still adding jobs, just at a slightly slower pace!

However, there are clear signs now that the U.S. labor market is cooling down. We might not know for sure the true pace of job creation until February of next year when the BLS will release its final benchmark revision for that period.

Meanwhile, the massive gap between labor demand and supply has shrunk substantially since 2022. Recruitment has gotten easier and CPAs (cost-per-application) are down because there are more available candidates for each open position as hiring is slowing down across sectors.

Consequently, Fed chair Powell remarked last week that the U.S. labor market is not overheated anymore and that rate cuts in September are justified. After bringing inflation almost back to target, the Fed has no intention to cool down the labor market further, nor should it, as it raises the risks of a self-inflicted economic downturn created by tight monetary policy.