GDP data showed an improving economy…

Last week it looked like the U.K. economy had shaken off the shallow recession that it experienced last year. The ONS monthly GDP figures showed that the first two months saw the economy return to growth, albeit at a slow pace. These preliminary numbers indicate that the U.K. economy expanded at a rate of 0.3% and 0.1% in January and February, respectively.

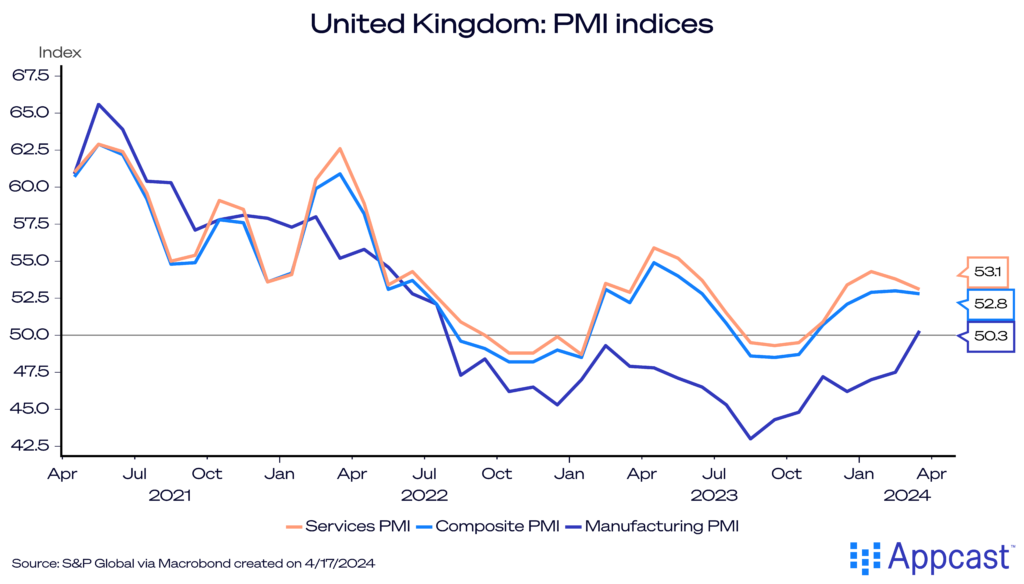

Moreover, for the first time since mid-2022, the manufacturing PMI (Purchasing Managers Index) is slightly exceeding 50 again, the threshold that separates economic contraction and expansion. With the services PMI remaining comfortably above 50, economic activity was supposedly picking up during the beginning of this year.

…but unfortunately, the labor market is telling a different story

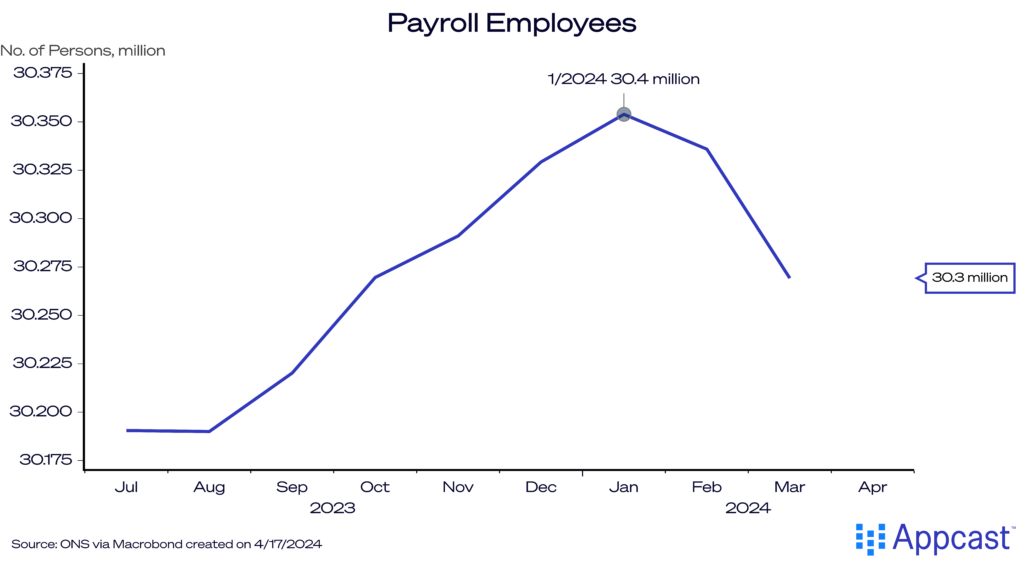

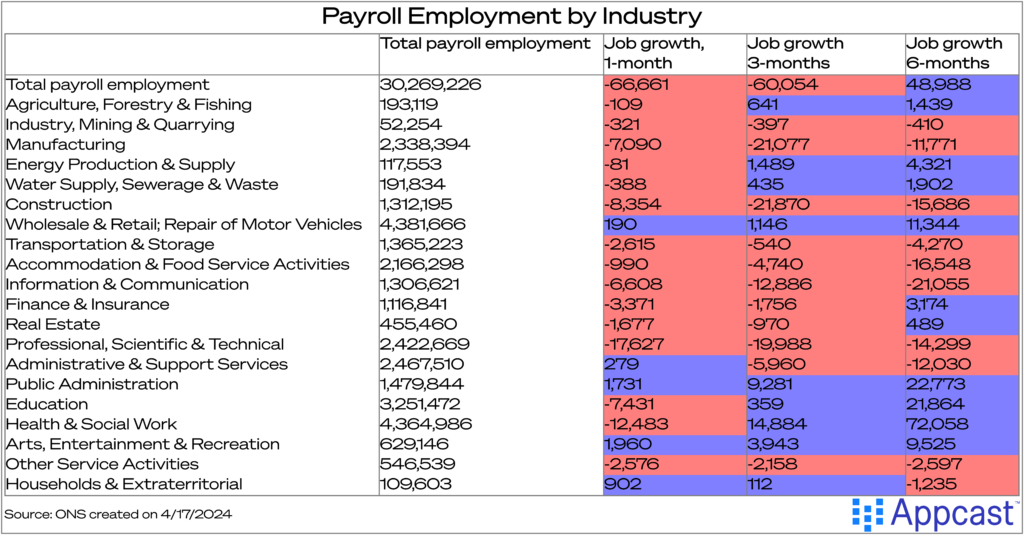

However, the most recent labor market data does not seem to confirm that the U.K. economy is out of the woods yet. On the contrary, the number of payroll jobs has actually fallen for two consecutive months and is down by almost one-hundred thousand since January. This is concerning because it is also a different dynamic from the end of last year when GDP was slightly contracting but employers were still creating jobs.

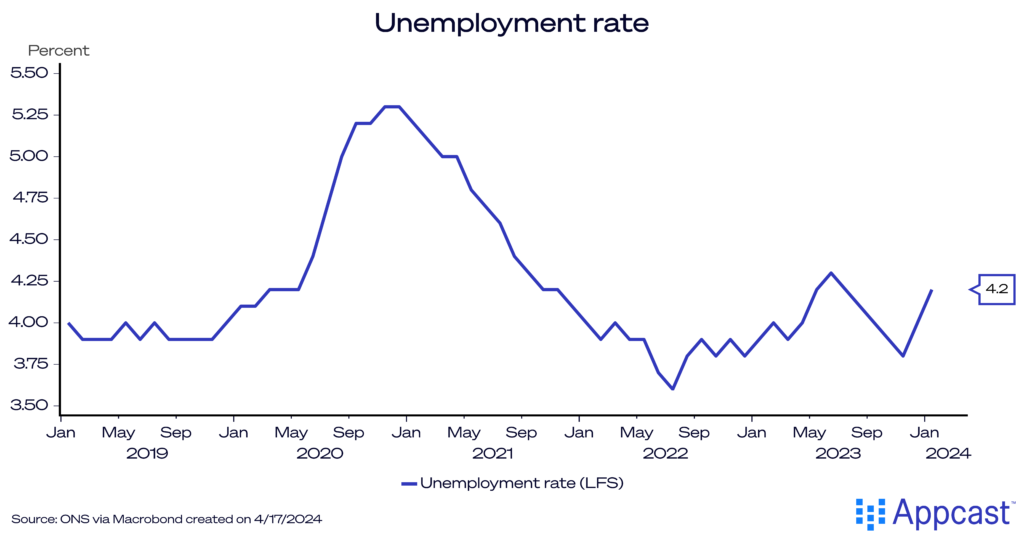

We have previously noted the problems the ONS has faced over the last year to correctly measure the unemployment rate and other related labor market data in the U.K. Due to extremely low response rates, estimates based on the Labour Force Survey should be treated with some caution. But since the ONS data is the only game in town, we do not have any other choice but to look at what the data is telling us.

And unfortunately, the story is not very pretty. The U.K. unemployment rate increased from 3.8% last November to 4.2% In January.

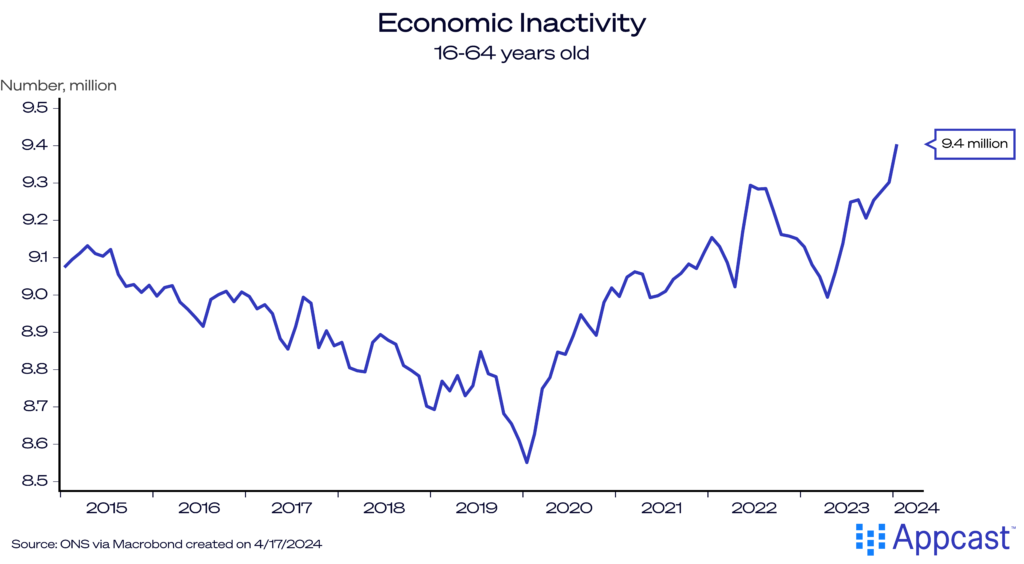

At the same time, economic inactivity – the number of people out of the labor force – has also increased by more than half a million people since 2018. As we noted previously, an increasing number of people in the U.K. are not working and not looking for work because of long-term sickness.

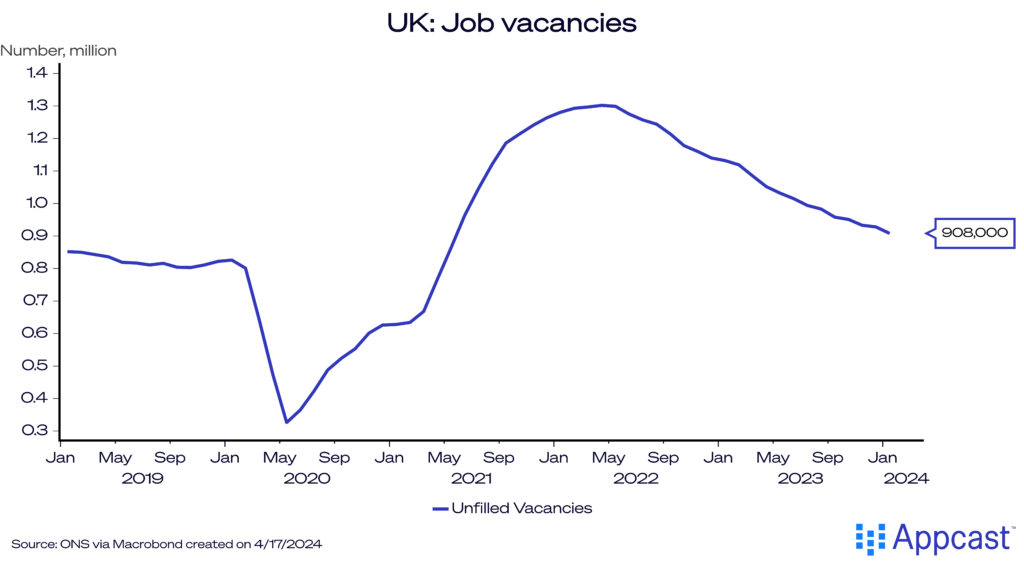

Finally, unfilled vacancies have now fallen for about 24 consecutive months and are now down to about 900,000. While this is still slightly above pre-pandemic levels, the trend is clearly not our friend here. All indicators are pointing towards a rapidly easing labor market.

If one is concerned about the accuracy of the data based on the Labour Force Survey, data based on payroll employment clearly show a deteriorating job market since the beginning of the year. While payroll employment is still up compared to six months ago, both the three-month and the one-month figure are now negative. Moreover, recent job losses are not just concentrated within one sector but rather widespread across many sectors.

Even as payroll numbers can be subject to large revisions, it is quite unlikely that the entirety of this broad-based decline will be revised away.

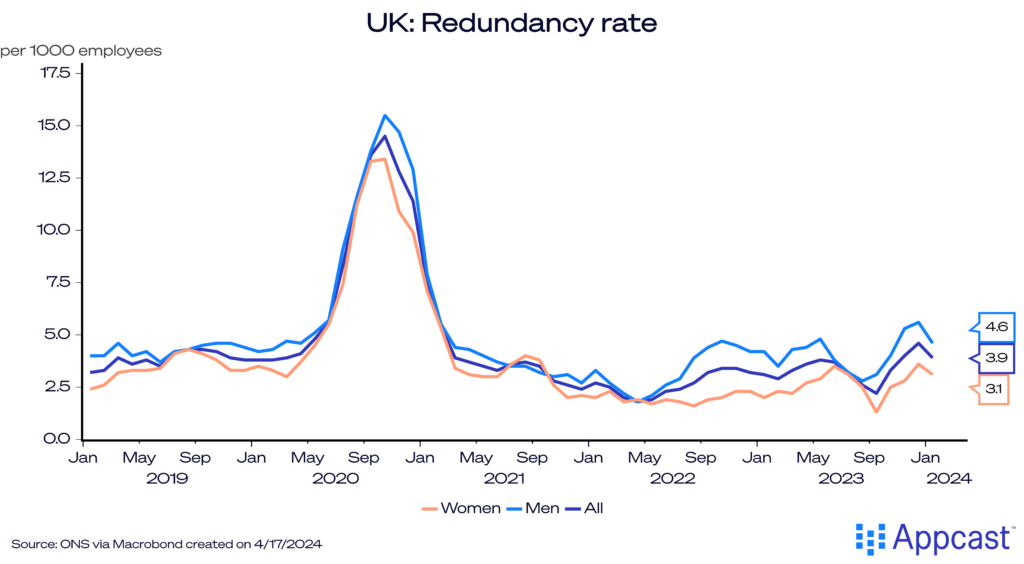

While redundancy rates are still relatively low, there has clearly been an upward trend over the last year with layoffs becoming more widespread. The redundancy rate has risen from below three per 1,000 employees in 2022 to about 4 per 1,000 employees at the beginning of this year.

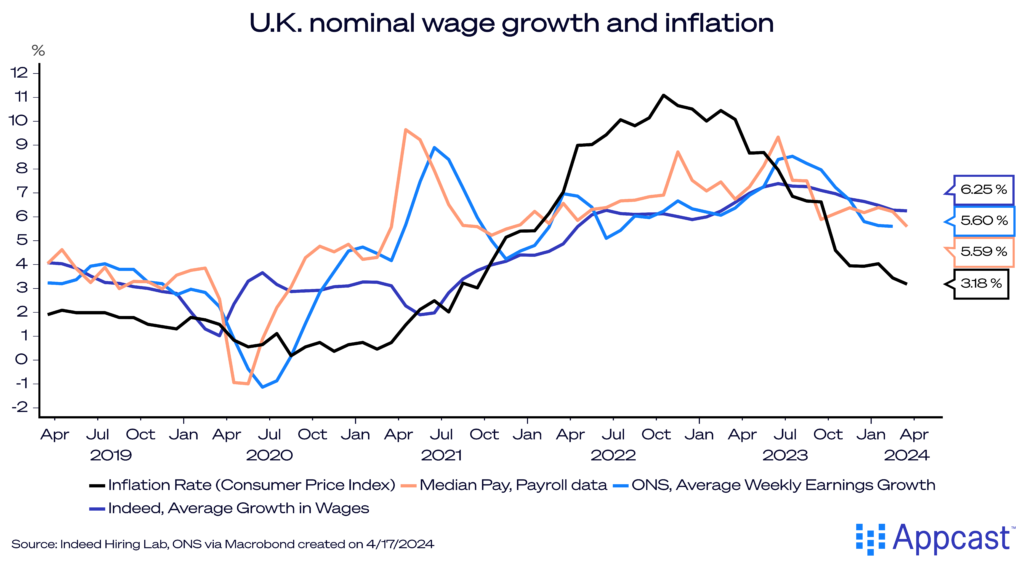

Inflation and wage growth exceed expectations

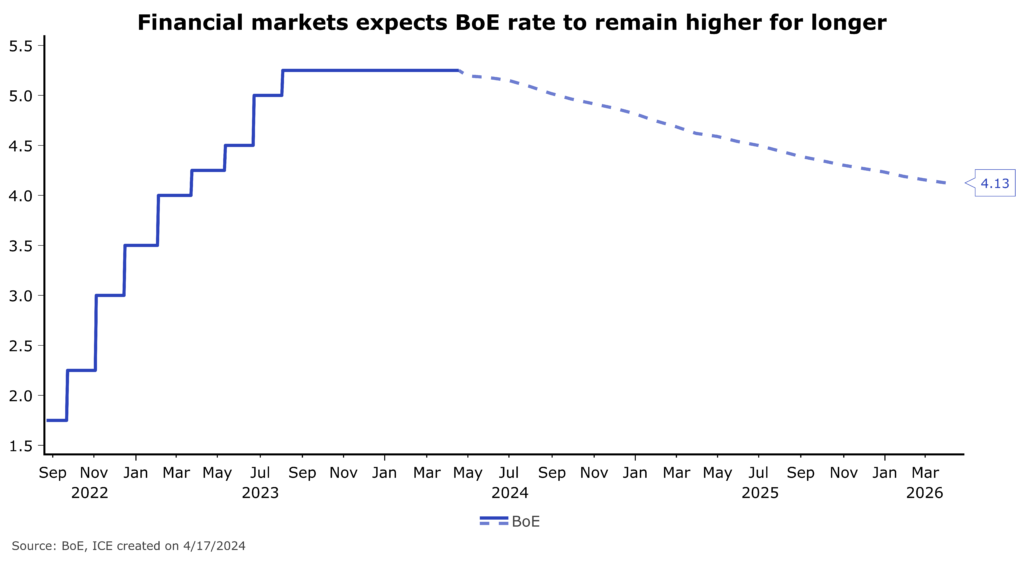

Equally concerning is the fact that both wage growth and inflation numbers came in hotter than expected this week despite a seemingly weakening labor market. This is troubling because it puts the Bank of England (BoE) in a very awkward position. The employment losses clearly indicate that the economy is suffering from tight monetary policy and that the BoE should cut rates. However, after two years of overshooting its inflation target, monetary policy makers are unlikely to move preemptively. The high wage growth and inflation numbers will push rate cuts further into the future.

Bond traders are now anticipating that the BoE will only cut rates once in 2024. This is pretty bad news since monetary policy is now clearly a headwind for the economy.

High interest rates are stifling the housing market and are depressing domestic consumption and investment. But as long as inflation remains stickier than expected, the BoE will not be able to cut rates any time soon.

Conclusion

Various labor market indicators are showing signs that the U.K. economy is not out of the woods yet. While GDP and PMI data indicate a timid recovery in the beginning of this year, labor market data has actually deteriorated. This is creating a severe headache for the BoE, which needs to see declining inflation and lower wage growth in order to be able to cut interest rates. But with both measures coming in higher than expected, interest rates will remain higher for longer even as labor market conditions are deteriorating.

Monetary policy is now a significant headwind for the economy and will depress economic activity throughout the year. With only one single rate cut priced in for 2024, do not expect a buzzing U.K. economy this year!