Over 2.7 million people were hired in the first half of 2022 – a shockingly good number. Yet there seems to be a chorus of negative economic news recently. With each new data release, the reaction in response is another r-word:

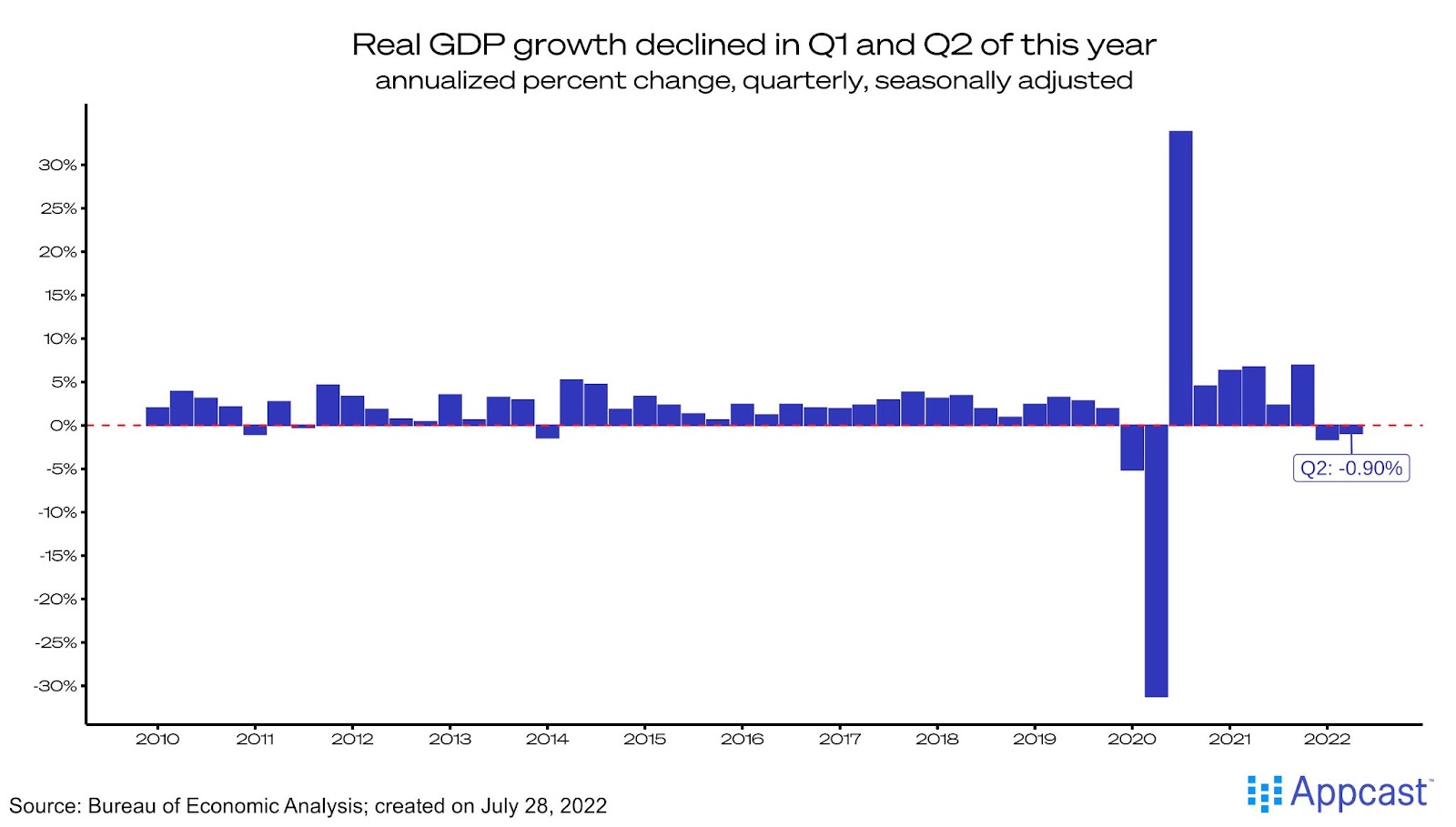

- Two quarters of negative real GDP growth – Recession!

- Inflation at a 40-year high while a war rages in Europe – Recession!

- The S&P 500 stock index down over 15% year-to-date – Recession!

Yet the labor market is still incredibly strong – the star pupil in the economic classroom. Can the U.S. be in recession with such strong job growth? No, is the answer Fed Chair Jay Powell gave at his July 27 press conference:

“I do not think the U.S. is currently in a recession. And the reason is there are just too many areas of the economy that are performing too well. And of course, I would point to the labor market, in particular.”

On July 28 we received another chorus of “recession!” reactions, as GDP growth went negative – U.S. economic output shrank in Q2. The most comprehensive measure of the goods and services produced – inflation-adjusted “real” GDP growth – declined at an annual rate of 0.9% in April through June. On the heels of a 1.6% decline in Q1, real GDP growth has now fallen for two consecutive quarters, but that doesn’t automatically mean the U.S. economy is in a recession (for guidance on all the indicators that factor into an “official” recession call, read this).

Growth is slowing in terms of GDP numbers, but inflation isn’t abating. One area of the economy the Fed hopes to cool off is the labor market. Make no mistake: the Fed’s 75 basis point interest rate hike on July 27, part of its sustained tightening cycle so far this year, is going to impact the labor market, eventually. But the labor market remains tight.

At Recruitonomics, we use the analogy of an overly-inflated sports ball as a representation of the US labor market; the Fed’s goal is to let some air out, but not so much as to make it unplayable. So, we say the labor market is depressurizing, not deflating. It’s getting less tight – but, so far, no meaningful slack has been introduced.

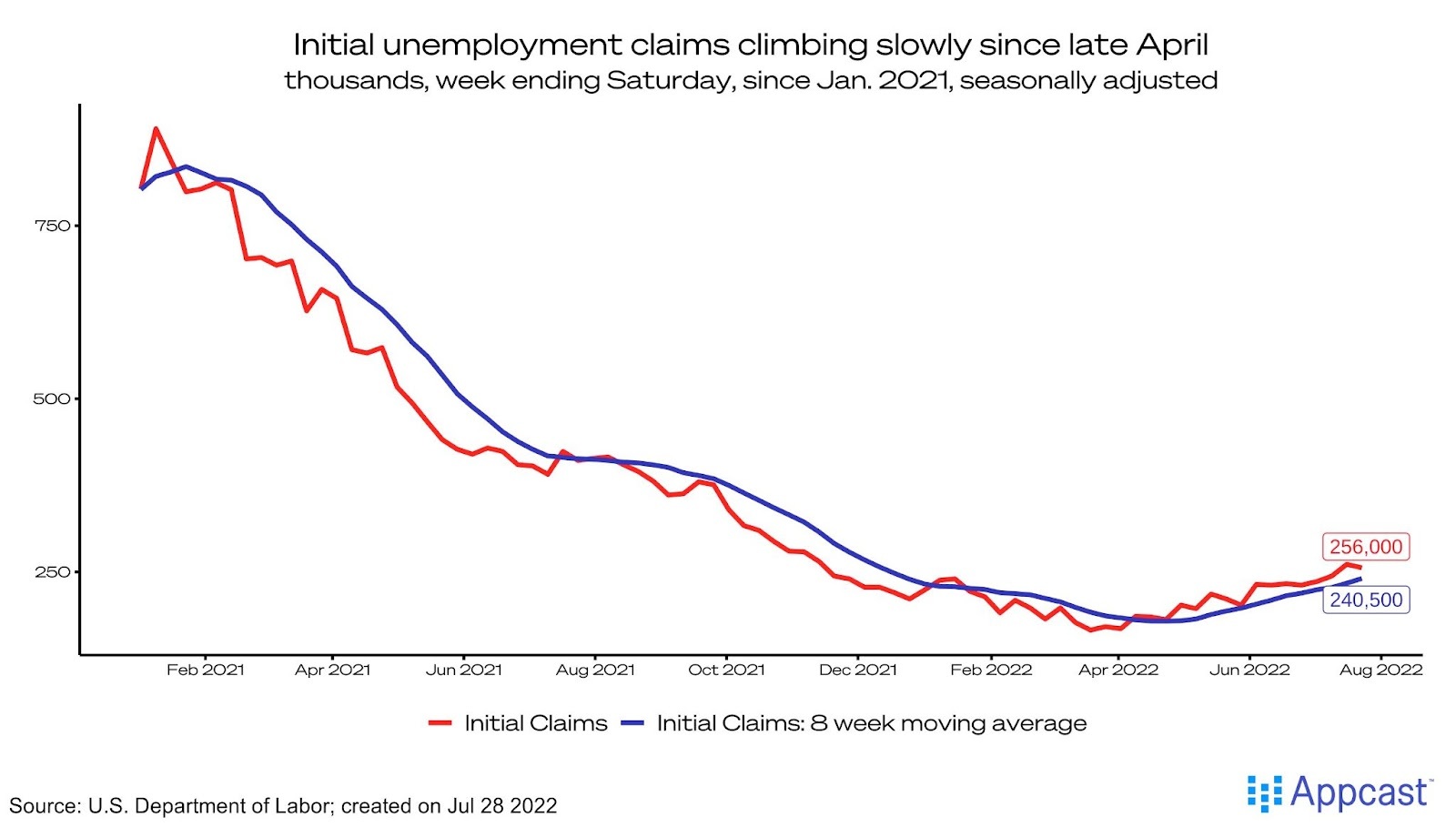

Yet, there are signs of cooling. Layoffs seem to be increasing slightly, as indicated most recently in the uptick in unemployment insurance (UI) claims. The 8-week moving average of initial unemployment claims has been creeping up since late April (see chart). But while these high-frequency measures of layoffs are up, they’re up from recent historical lows; and continuing claims – the total number of job seekers claiming UI benefits – has not risen as much. Keep in mind that the range of initial claims is still well below the 2014 to 2017 period, when the labor market had recouped losses from a recession (as we are now). While layoffs may be above the very tight levels seen before the pandemic (and earlier this year), trends are still below periods that clearly weren’t recessionary. Yes, perhaps the unemployment rate will increase in Q3 and Q4 – from its near 50-year low of 3.6%.

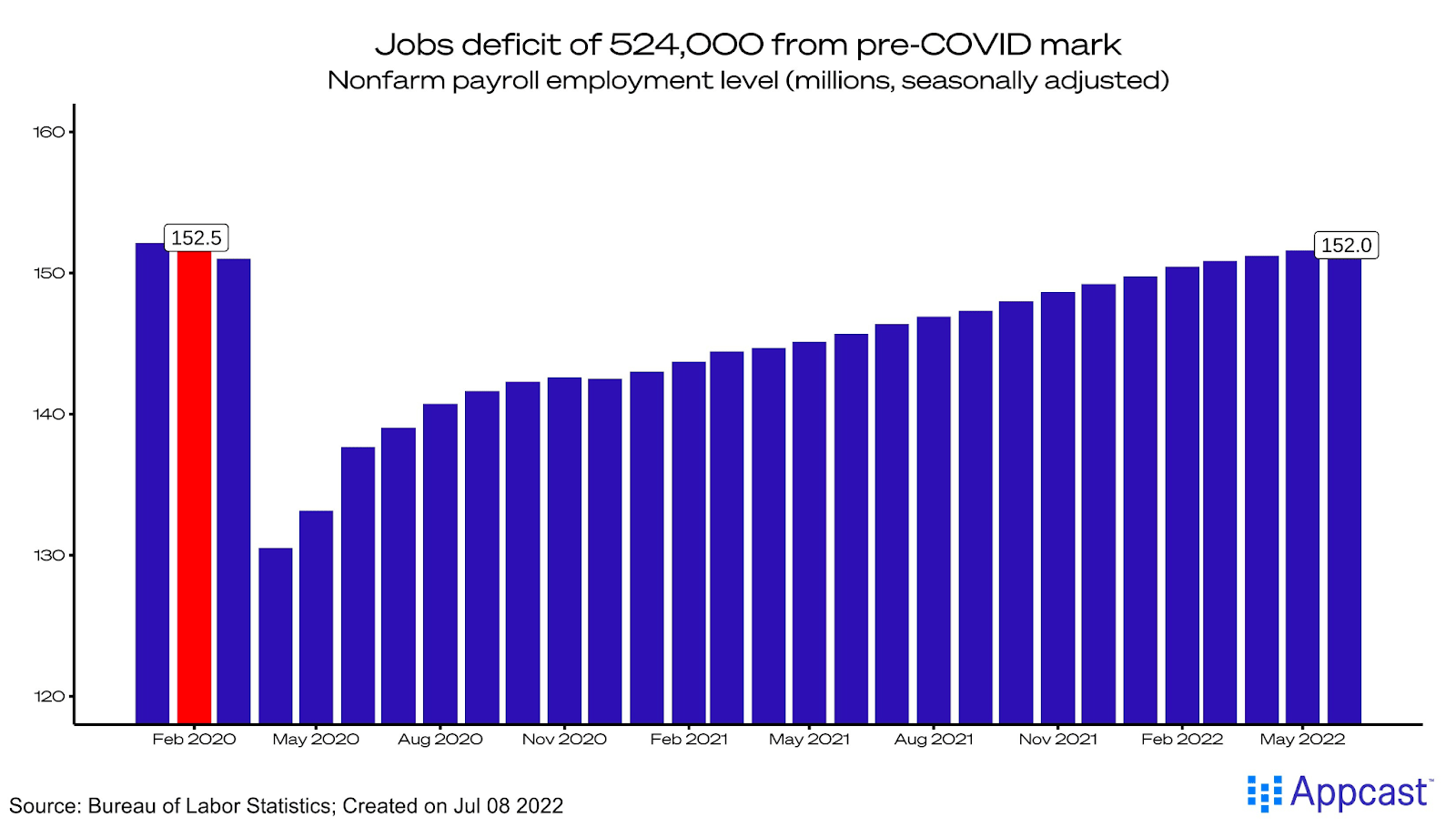

So even if other recession indicators are flashing “yellow” – such as weak GDP growth, a stock market correction, cooling housing market – there is no sign of a recession in the labor market at the moment. Not yet. You could even still call it a “worker’s market.” Look no further than the 11.3 million job openings in May paired with fewer than 6 million unemployed persons – a nearly 2-to-1 ratio. Or the stunning run of job gains that may surpass 3 million through July (we’ll see if that happens in next week’s jobs report).

You can expect a pivotal series of data over the next eight days: on July 29, consumer spending and the best overall measure of wage inflation (the Employment Cost Index); on August 2, the latest job openings and layoff figures; and on August 5, the July employment report. Pay close attention to the next two CPI reports (on August 10 and September 13). The Fed has made clear that interest rate hikes will not cease until the inflation curve begins to bend. Price stability will be achieved, the Fed says, no matter if the labor market begins to soften.

I’ll conclude by quoting Jay Powell again:

“We actually think we need a period of growth below potential, in order to create some slack so that the supply side can catch up. We also think that there will be, in all likelihood, some softening in labor market conditions.”

The Fed’s ultimate goal is price stability (long-term inflation around 2%), and interest rates are its blunt but powerful tool for slowing demand in the economy. If it intends to take a bite out of the labor market, the rising UI claims are evidence of that.

The opportunity to reduce inflation in coming months while sustaining a tight labor market is diminishing.