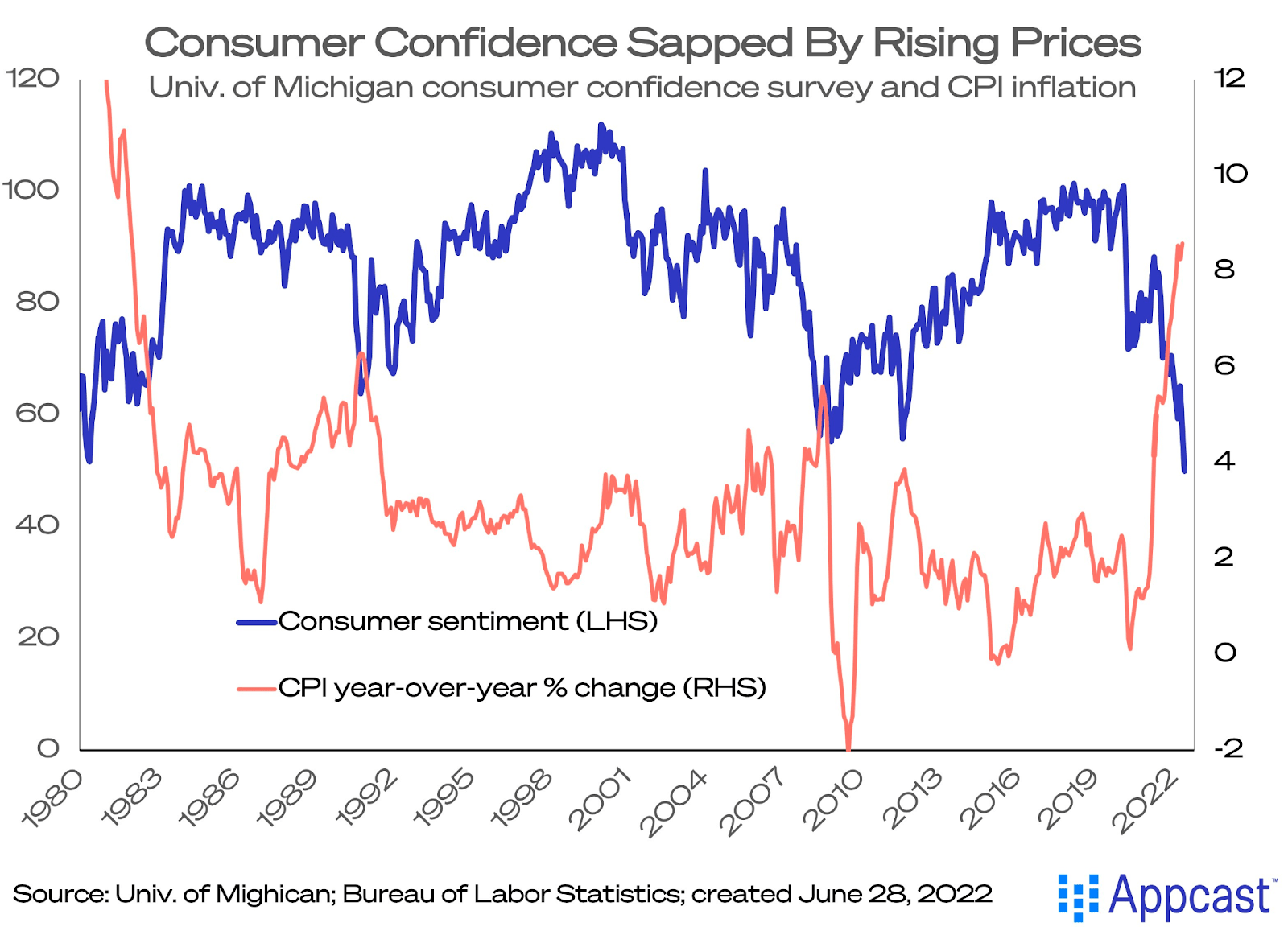

Inflation is on everyone’s mind, and the mood is souring. The University of Michigan’s Survey of Consumers for June was released last week and the numbers were dismal; consumers are not betting that inflation will turn the corner. Consumer confidence hit a record low in June, with consumers reporting high levels of uncertainty and blaming inflation for eroding their standards of living. Just yesterday, the Conference Board released their Consumer Confidence Index for June. They also reported declining consumer confidence, including the lowest measure of short-term economic expectations since March 2013.

These surveys, especially the University of Michigan’s, are oft-cited in reports and decisions about inflation, recessions, and general economic woes. Recently, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell confirmed that declining consumer sentiment weighed into the decision to raise the interest rate by 75 basis points. These lowest and latest numbers will no doubt factor into future decisions on interest rate movements.

The US has not experienced a destructive bout of inflation in nearly 40 years, and many consumers feel unsure of how to navigate rapidly rising prices. Similarly to the last instance of sustained inflation above 5-percent, in the 1980s, Americans are facing crippling energy prices that have seeped into the rest of the economy. In May of 1980, the previous record-low was reported by the University of Michigan’s index. Inflation was soaring; in that month, it came in at 14.4%. There is a marked disconnect between the levels of inflation consumers are experiencing today and the level of consumer confidence compared to the 1980s. This could be due to increased uncertainty following the COVID-19 pandemic, increased levels of political polarization, more consistent messaging from news outlets and social media, or a combination of these inputs and more.

Inflation is, by nature, impossible to avoid, but making consumers hyper-aware of it can create a worrisome paradox. An inflationary environment is a dangerous one to navigate. Its true causes are hard to pinpoint, even for the most knowledgeable economists, and trying to diffuse it can often cause harmful side effects, like increased unemployment. What is known is that inflation has the power to be a self-fulfilling prophecy, often adhering to consumers and businesses’ expectations.

The University of Michigan’s and the Conference Board’s consumer confidence indexes will factor into the Fed’s future decisions about inflation, whether these reports are a true reflection of economic conditions, or a response to an uptick in economic reporting and a fraught political situation. If it is the latter, the Fed would be wise to focus on curing economic conditions, rather than catering to consumer sentiment.