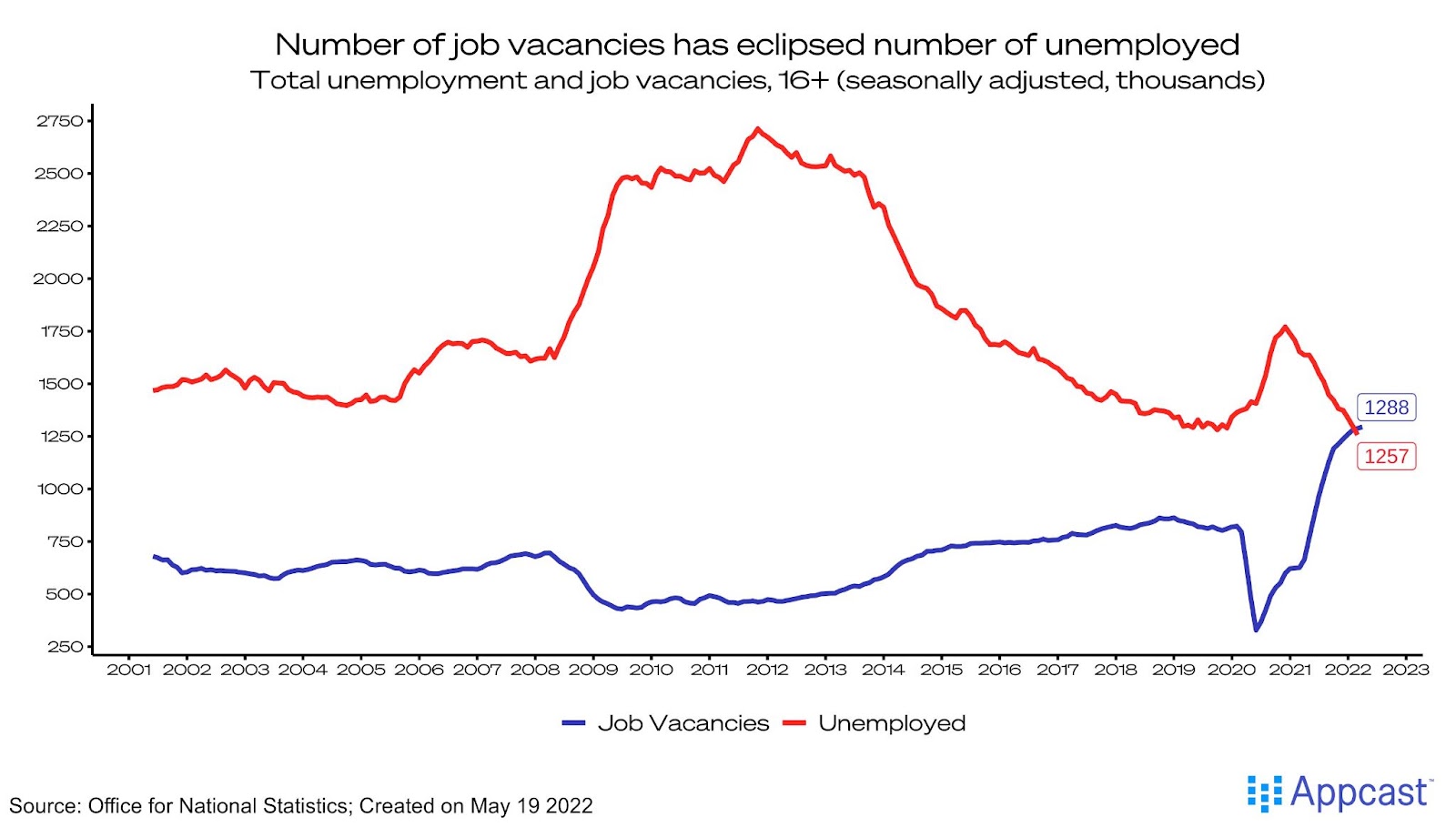

First, start with the paradoxical good news: job vacancies are booming and now exceed unemployed persons for the first time ever. Job vacancies hit a record high of 1.288 million, while the number of unemployed persons dipped down to 1.257 million. Demand for workers is about 60% above its pre-COVID level. The paradox is that while the U.K. labour market is extremely ‘tight’ – a good thing for workers – those same workers are suffering from a cost of living crisis.

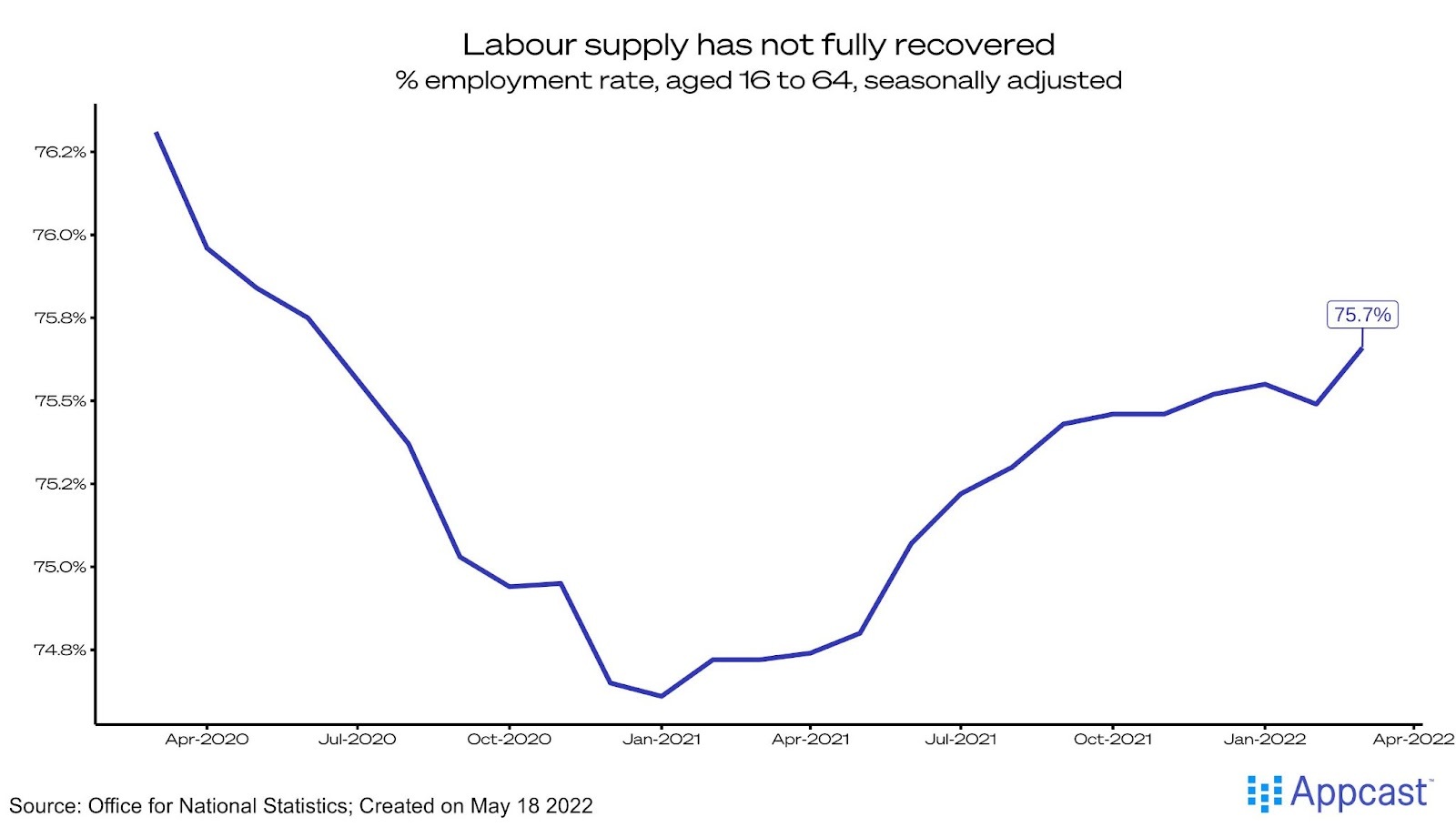

Yet job seekers haven’t returned to the labour force, despite COVID cases receding to a one-year low. A smaller share of workers are employed now than in the pre-COVID era: the employment rate of 16 to 64 year olds is at 75.7%, about a half percentage point below the early 2020 mark. This phenomenon – that anyone who wants a job can get one, but many without a job aren’t searching – has driven the unemployment rate down to 3.7%, the lowest in nearly 50 years.

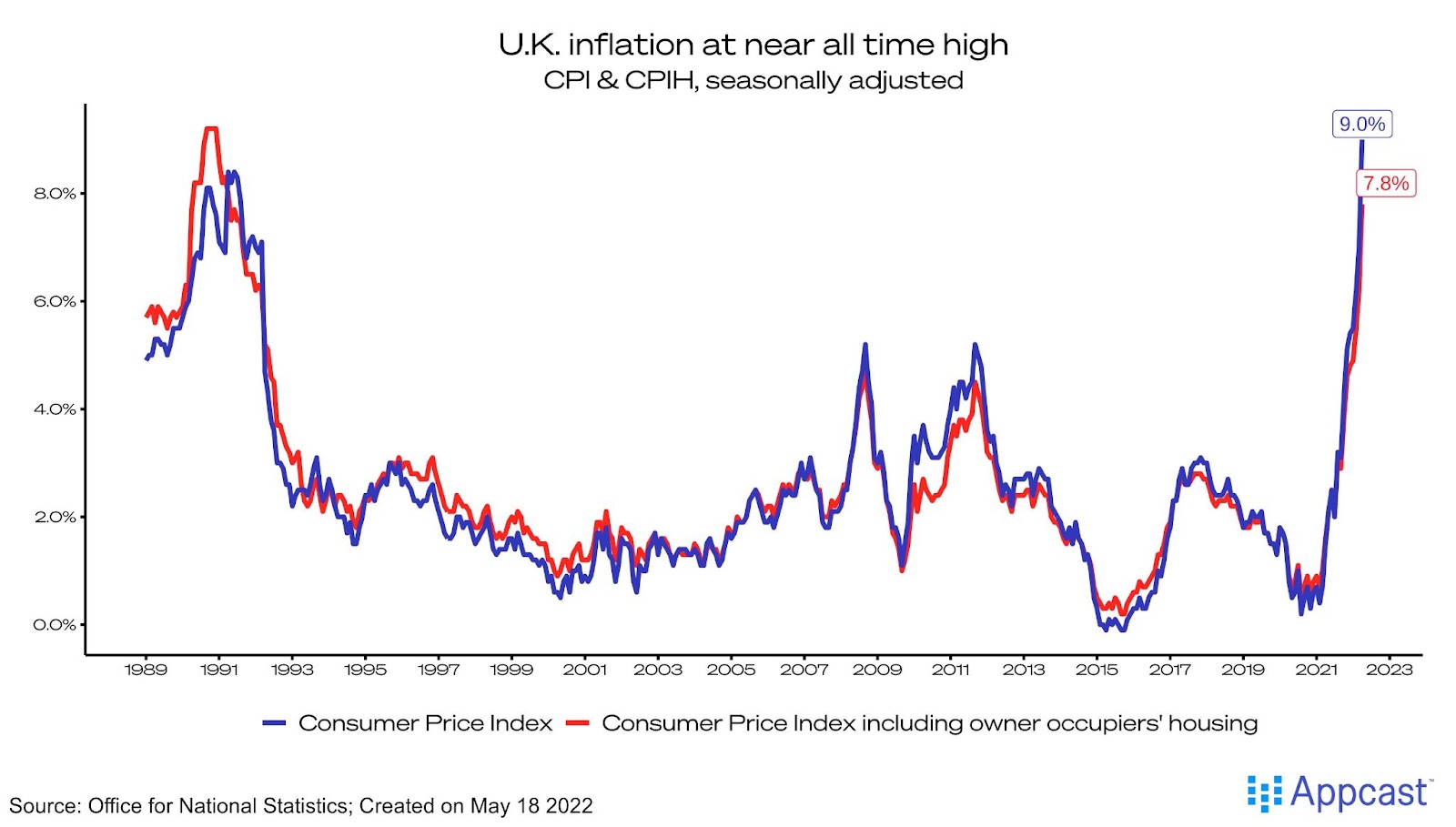

Meanwhile, job gains and GDP growth have been lackluster, and war in Eastern Europe has pushed the headline CPI inflation series to a 40-year high of 9% year-over-year. The more-reliable measure of inflation, CPIH (which includes owner occupied housing costs), is still very elevated, up 7.8% from a year prior.

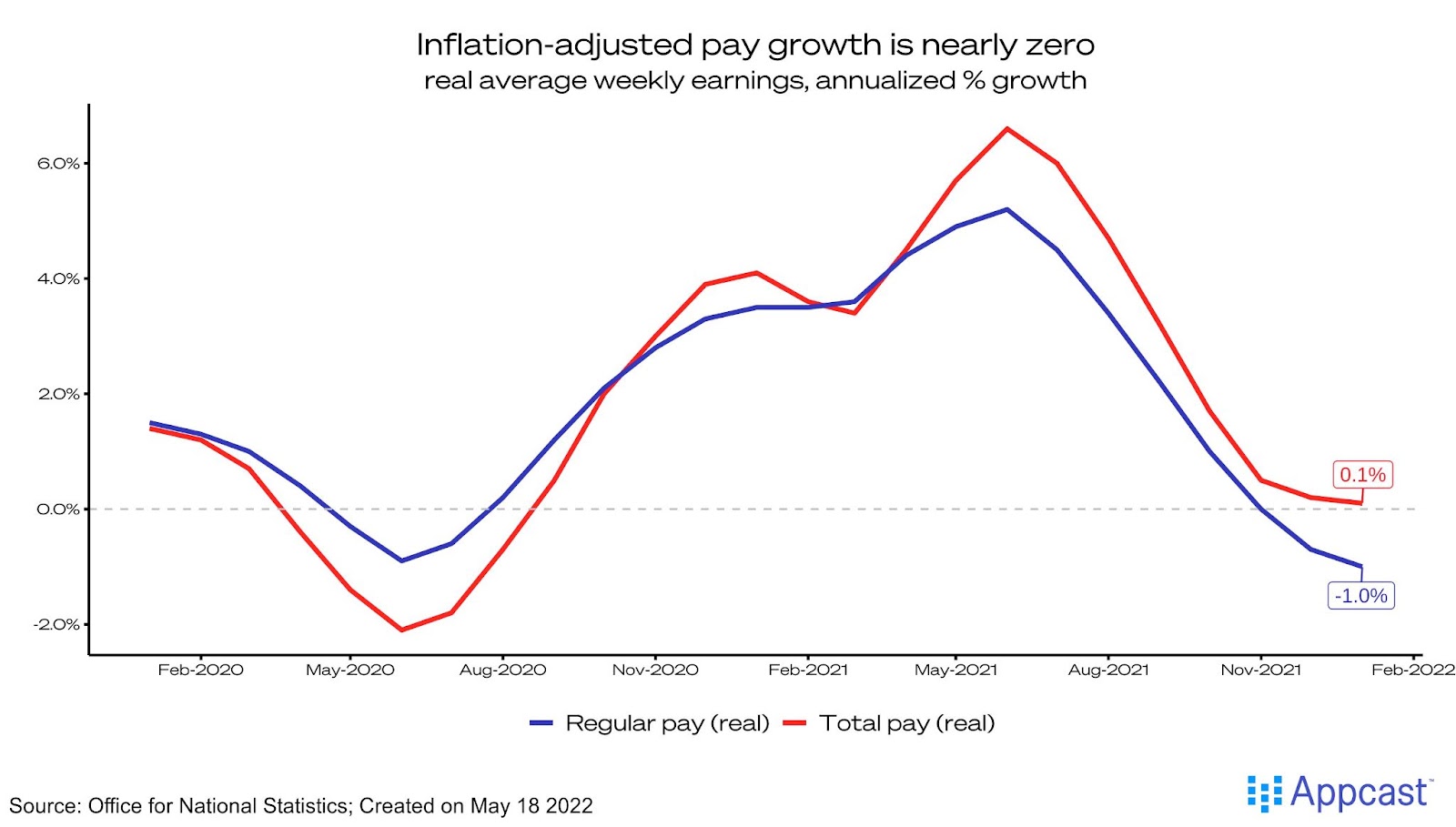

The cost of living crisis is real, as earnings adjusted for inflation have turned negative for most workers. And it’s not projected to get better anytime soon: The Bank of England warns inflation could top 10% later this year. High inflation is behind the BoE hikes in its main interest rate to 1%, but lackluster growth signals rising recession risks.

This combination of labour shortages and crushing inflation means U.K. employers, now more than ever, need to get creative to attract top talent. And U.K. policy makers must act to increase labour supply in a post-Brexit environment.