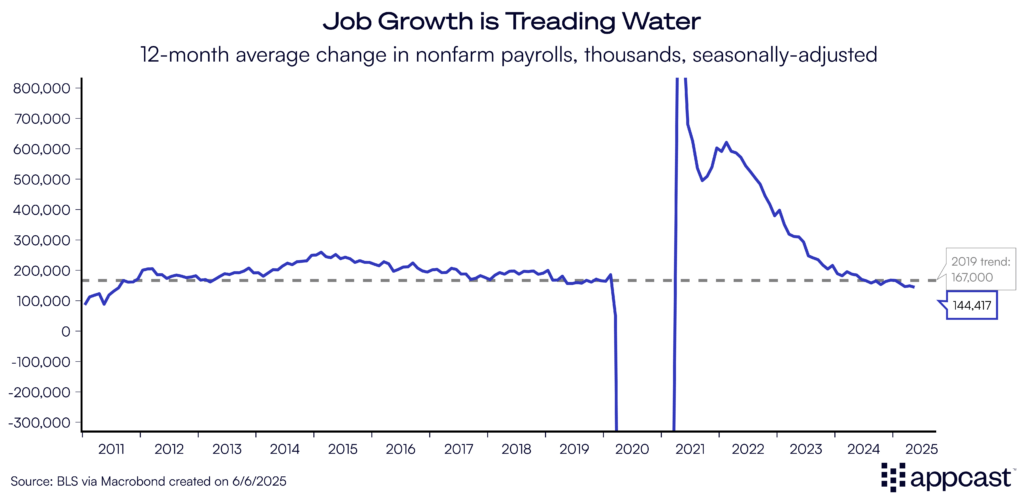

The U.S. labor market added 139,000 jobs in May, which on its face isn’t bad. However, the average monthly job gains over the past year have slowed to about 144,000, which is the lowest level since late 2011 (excluding the sharp pandemic-era drop). So, the labor market is treading water. Unemployment can remain roughly stable, and the current labor market health can be sustained if job growth continues at this current pace, but any further slippage will be a warning sign.

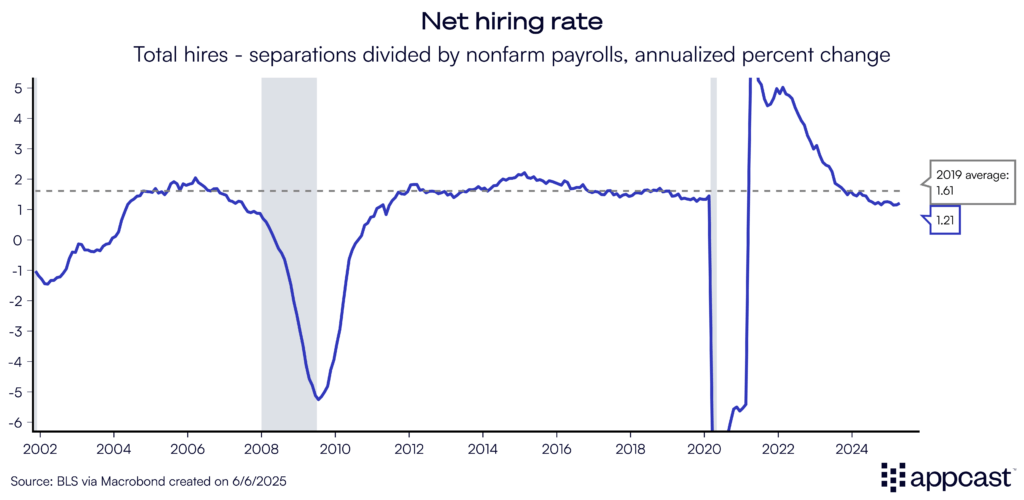

On a nerdier note, the net hiring rate has shifted down to 1.2%, well below pre-pandemic trends. Again, the current levels of job growth and hiring rates are not alarming. It’s that the cooling trend has now hit the point that any further deterioration will push unemployment up further.

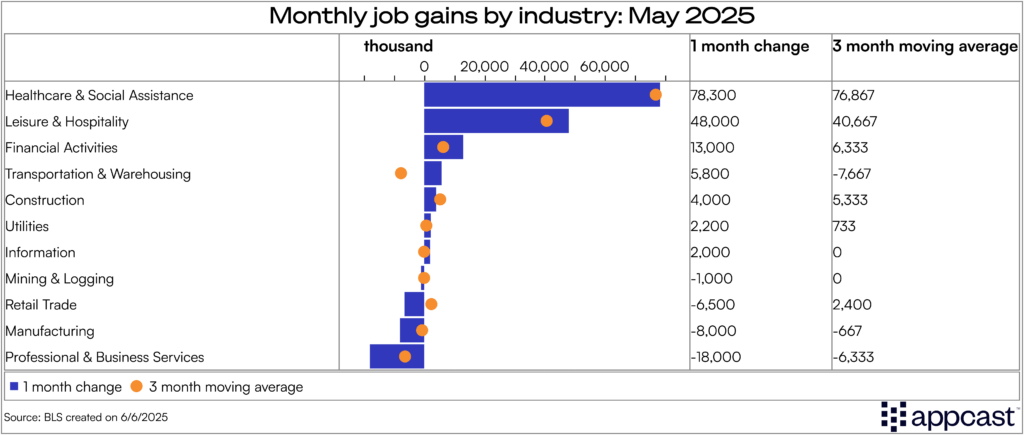

Really only two sectors made up the bulk of all job growth – healthcare and social assistance (+78k) and leisure and hospitality (+48k). Beyond those sectors, there were signs that professional and business services job growth has weakened further, with the three-month moving average now negative.

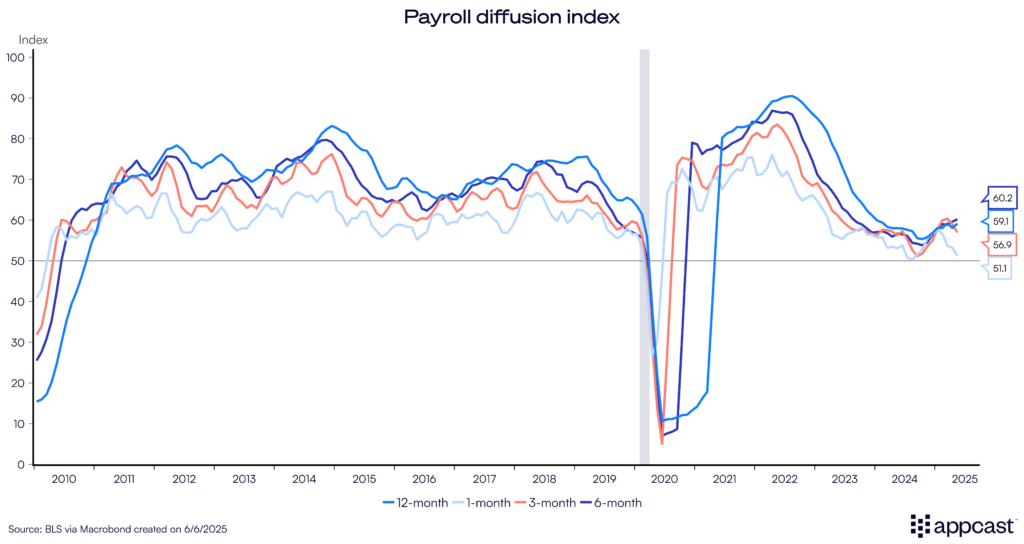

The “diffusion index” (which measures the breadth of job growth) fell near the lowest point of this cycle. This concentration of job growth in a few sectors is a warning sign going forward. A concentrated labor market is more vulnerable to sharp declines and does not allow for widespread job growth.

It’s all about policy

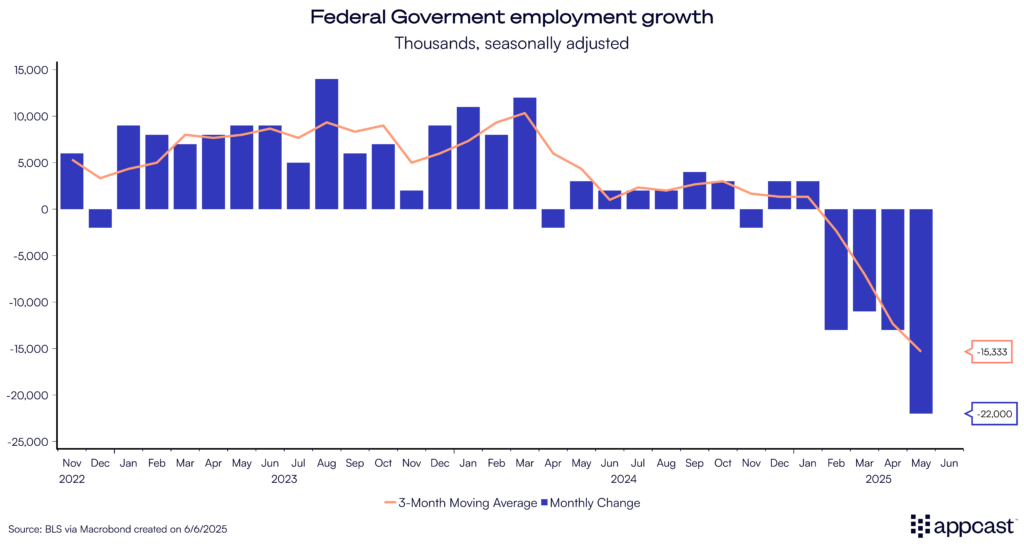

The biggest threat to the labor market is public policy coming out of Washington D.C. Tariffs have been the economic story since the April 2nd “Liberation Day” announcement, and 60 days later it’s materialized in contracting retail and warehousing employment. Moreover, the DOGE-led effort to trim government bureaucrats is having real effects, with a -22k job contraction in the federal workforce.

A longer-term risk factor for the labor market is the proposed Medicaid cuts in the “One Big, Beautiful Bill” that passed the House and now sits with the Senate. If the cuts in the House bill become law, hiring demand in healthcare could cool significantly. That is bad news for labor market because healthcare has been the number one contributor to job growth in 2024 continuing into 2025. Softening that tailwind would be detrimental for the labor market.

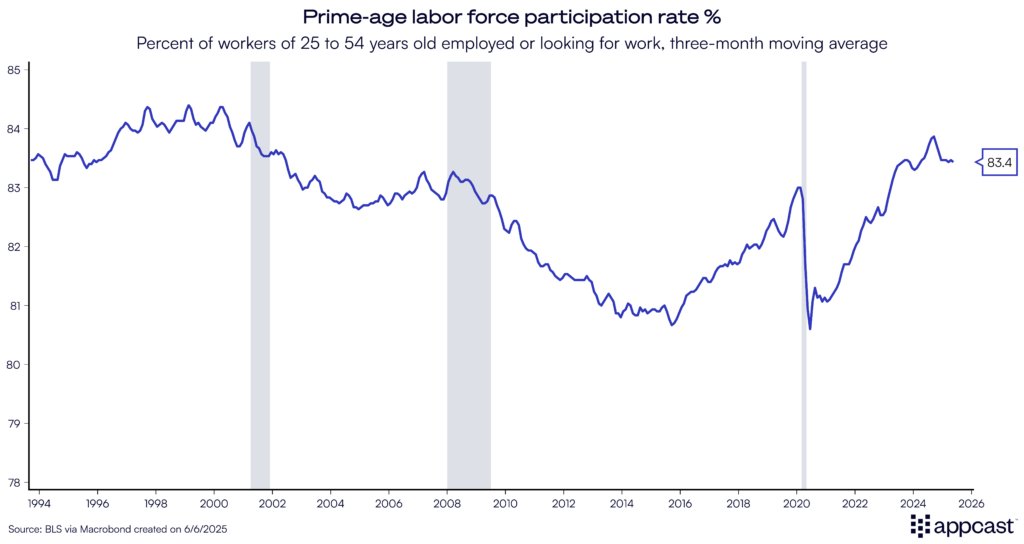

At the moment, the unemployment rate is holding steady at 4.2%. Though layoffs haven’t risen, the real reason for the unemployment rate’s steadiness is not good: The labor force has shrunk considerably. Focusing on prime-age workers, labor force participation slipped to 83.4%—still relatively high compared to the decade prior to the pandemic, but now a confirmed trend in the wrong direction.

Another worrisome sign has been the steady rise in the unemployment rate for workers 20-24 years old, typically graduating from college and entering the workforce full-time. Steadily rising to 8.2%, fresh grads are facing a labor market with fewer job opportunities which is putting upward pressure on the overall unemployment rate.

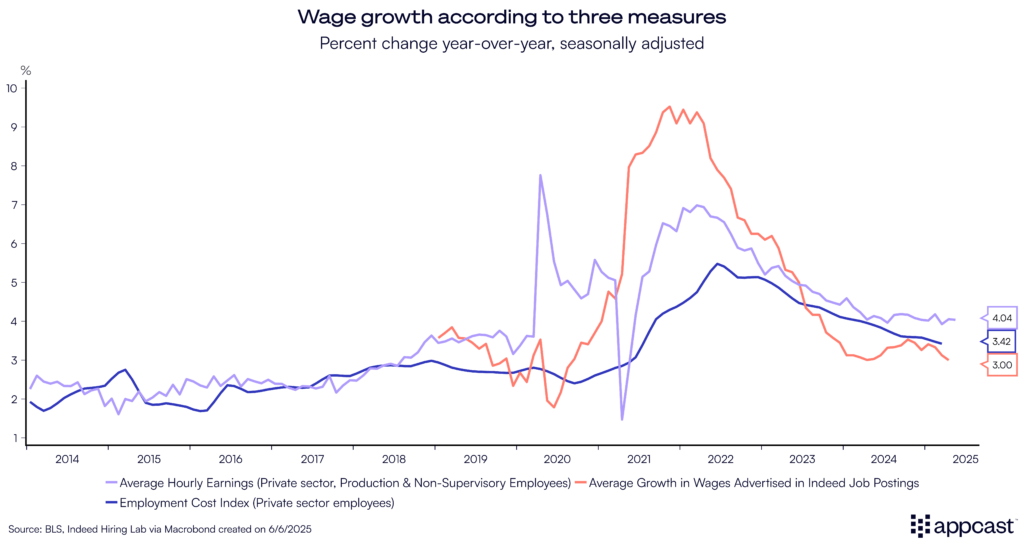

Wage growth has begun to show worrying signs of stubbornness. Average hourly earnings have held steady at 4% annualized growth, perhaps catching the Fed’s attention, and not in a good way. The outlook is trending towards stagflation: slowing job growth with public policy creating upward pressures on prices and wages. This puts the Fed in a bind.

What does this mean for recruitment?

The outlook for jobs and inflation hinges on government policy. Congress may very well enact Medicaid cuts that could kill the golden goose (healthcare hiring). The president may very well continue an on-again/off-again tariff policy, from which the associated uncertainty could chill business expansion. Restrictive immigration policy might sustain hot wage growth. And all these policies together give the Fed a mighty challenge to enact its plan for further rate cuts.