Workers with disabilities have suffered from the inaccessibility of the American world of work for decades but not for lack of trying. Ferocious, grassroots organization by the disability rights movement throughout the 1970s and 1980s led to the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act in 1990. This historic act codified the inclusion of Americans with disabilities, but accommodating the basic needs of workers with disabilities has proven difficult in the over thirty years since. For instance, the Bureau of Labor Statistics didn’t even start tracking labor force data for workers with disabilities until 2008! Without consistent, visible data, tangible change is hard to achieve.

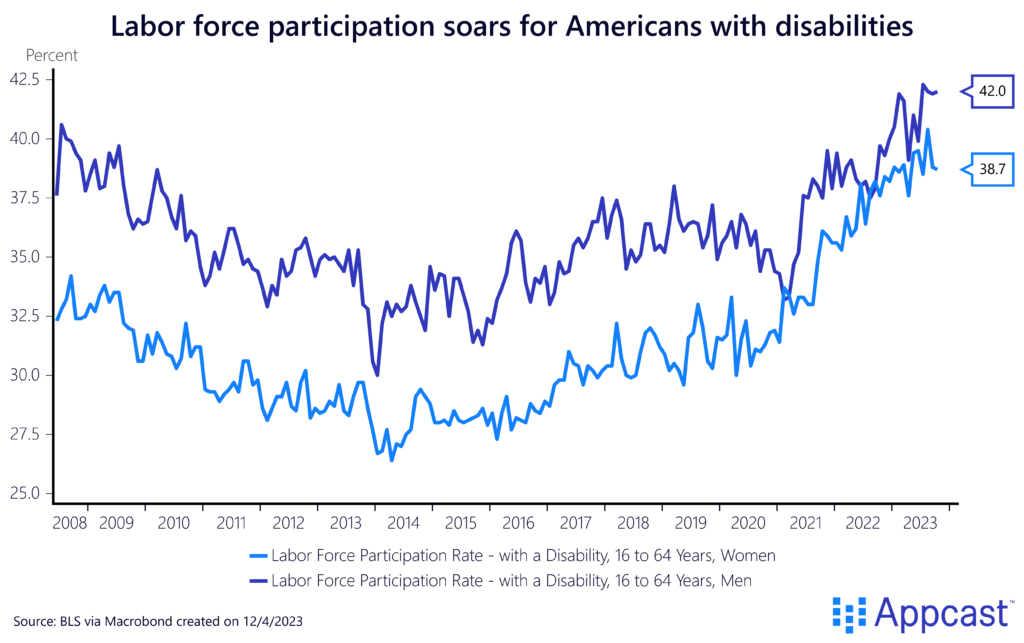

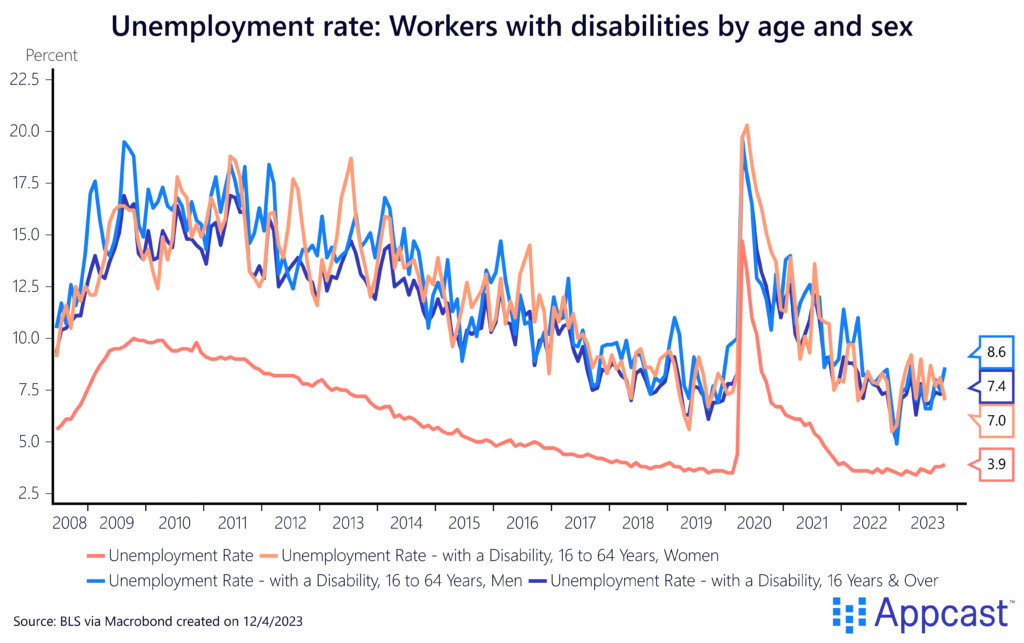

However, certain trends in recent years have positively impacted the labor force outcomes of workers with disabilities. Labor force participation among the population has skyrocketed for both men and women, with unemployment falling to record lows.

The benefits of a tight labor market

The post-pandemic labor market has been the tightest seen in decades: Job openings have soared to unprecedented levels, unemployment rates for nearly all groups have sunk to historical lows, and wages have risen fast – uncomfortably so, given the rate of inflation – indicating elevated worker power.

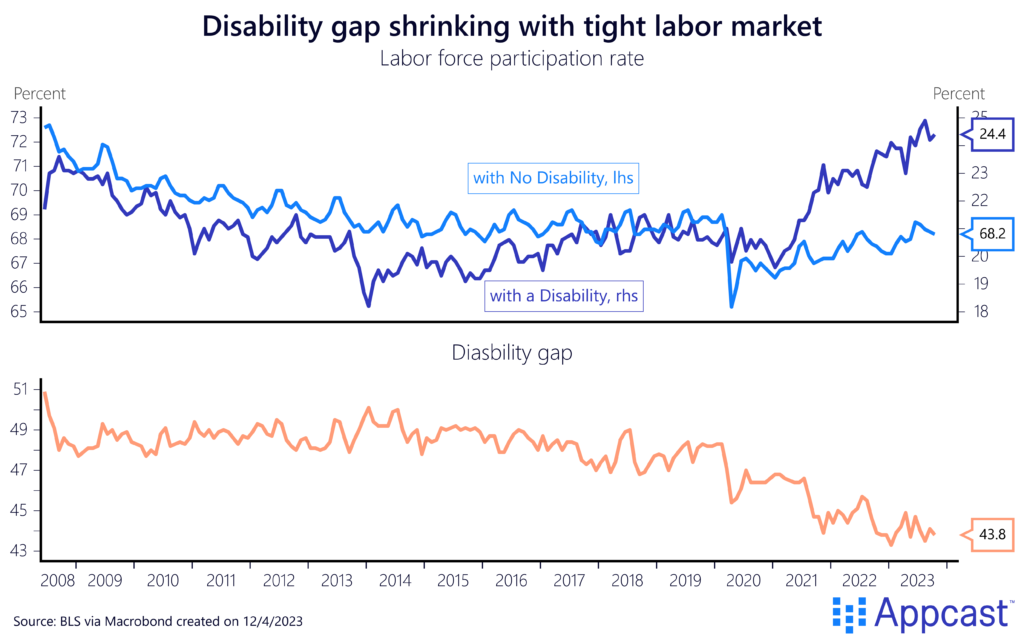

Tight labor markets boost job opportunities for all disadvantaged job seekers: Unemployment rates have fallen to historic lows for workers in minority groups, and disabled workers are no exception. In December of 2022, the unemployment rate for those with a disability fell to a historic low of 5.0%. This rate has climbed a bit since but has remained low compared to norms in the 2000s and 2010s.

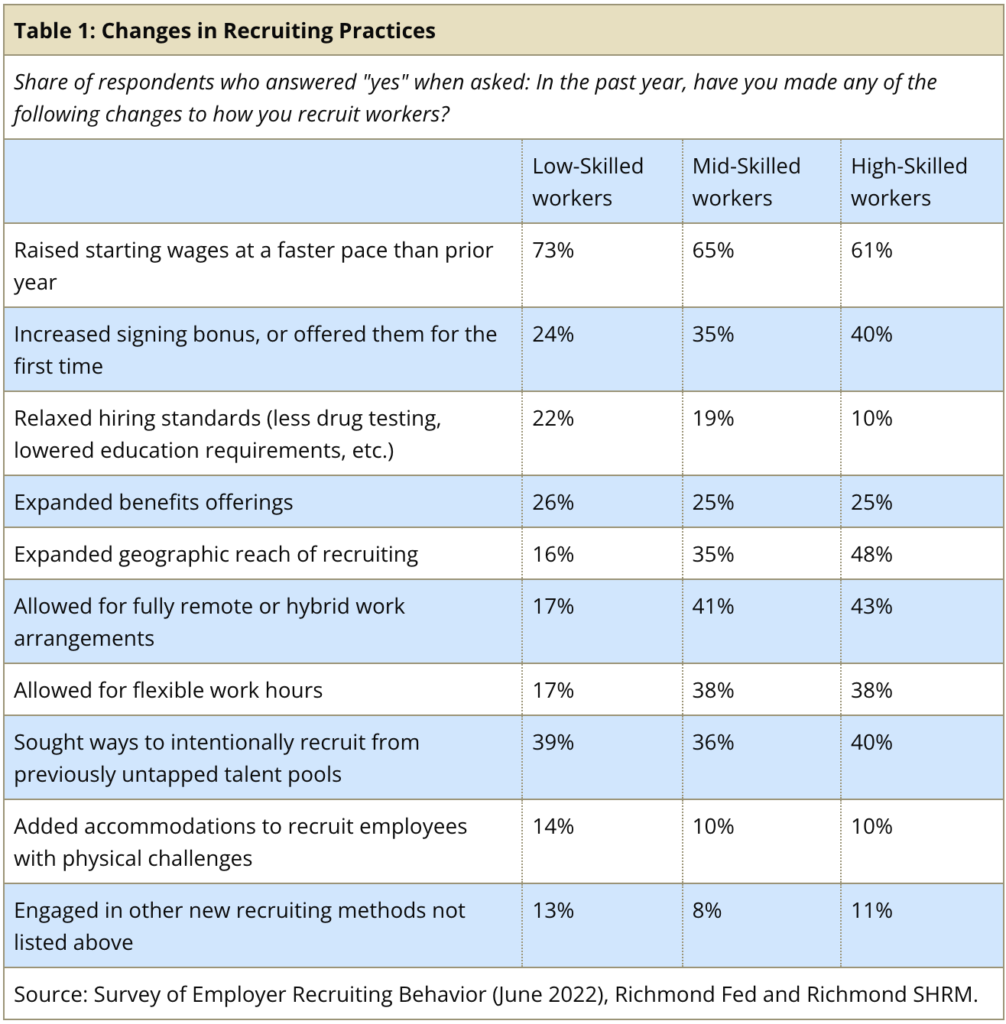

When demand for workers is hot, employers expand their hiring pools. For instance, during the tightest points of the labor market, employers stripped down requirements like advanced degrees, certifications, and more. They also pulled out all the stops in offerings. Yes, wages and benefits increased, but so did accommodations for workers with physical challenges — and, of course, the expansion of the geographic reach with work-from-home offerings. A survey from the Richmond Federal Reserve shows that 14% of recruiters searching for low-skilled working added accommodations to recruit employees with physical challenges.

With the influence of a tight labor market, the “disability gap” – or the historically large employment gap between workers with a disability and without – has fallen to a historic low in recent years, now at 43.8%. Workers with disabilities are truly enjoying more employment opportunities compared to before the pandemic, in part because of an exciting innovation in the way we work.

Though the labor market is cooling, it remains historically tight. Demand will continue to soften into 2024 but not completely fold (barring a devastating recession). However, the population of the United States is quickly aging, which will naturally lead to an increase in the number of Americans with disabilities.

WFH has had a profound impact on workers with disabilities, but it is not one-size-fits-all

Along with a tight labor market, the pandemic also ushered in a new way of working: The ability to work from home has allowed more workers with disabilities to join the labor force. Americans with disabilities could finally work from spaces already suitably accessible to them, as they had been asking for since before the passage of the ADA.

Though working from home (WFH) is not as widespread as it was during the pandemic, 28% of working days were worked from home in the U.S. by all workers in October 2023, with even more (40%) by those who can work from home. Despite employers’ misgivings, WFH has been nearly impossible to roll back completely.

However, remote work is not the one-size-fits-all solution to assisting workers with disabilities. In fact, the retail industry, famously not remote-friendly, was the second largest employer of disabled workers in 2022 after education and health services, with the leisure and hospitality sector not far behind (13.4%, 20.7%, and 9.9%, respectively). All three industries are decidedly in-person.

Bringing disabled workers permanently into the labor force will require creative, individualistic responses that businesses have been historically wary to implement.

The long shadow of COVID-19

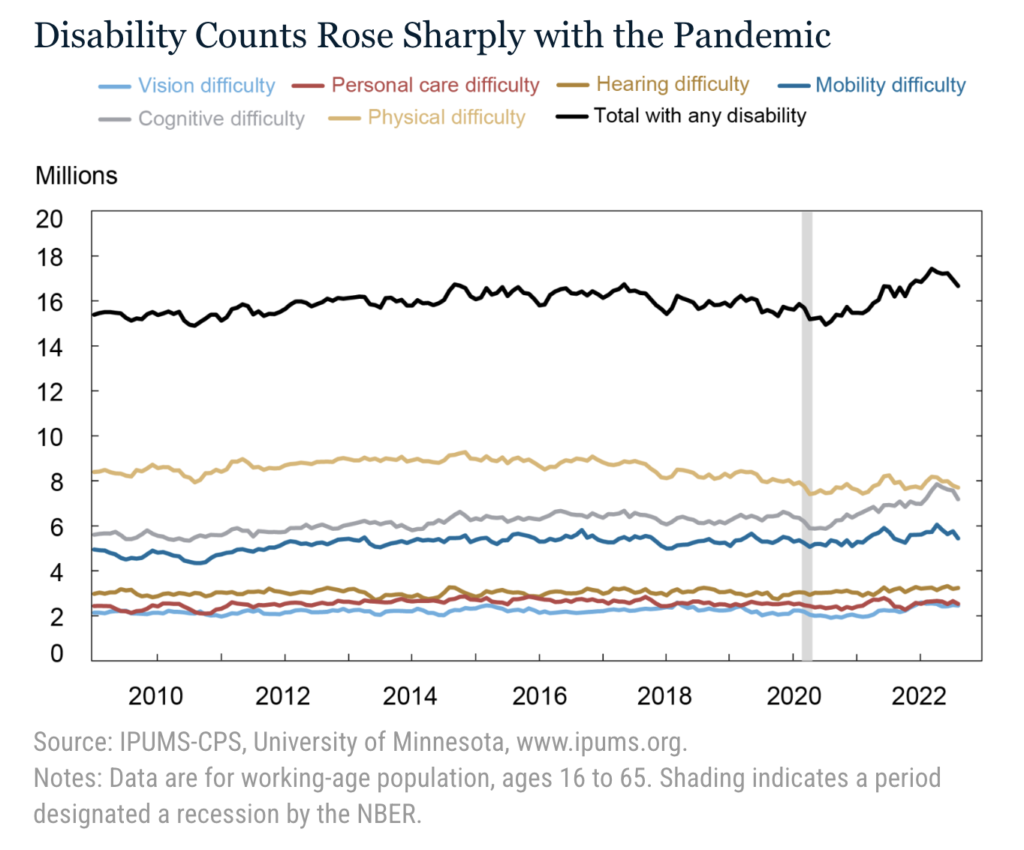

From 2021 to 2022, the number of workers employed with a cognitive disability increased by 23.1%, according to the 1-year ACS, while the total number of workers with a disability increased by just 13.0%, according to the same survey.

It could be that cognitive disabilities are becoming more common. In part, this could be an impact of long COVID — as it neatly followed the pandemic — or a broader impact of a shift in the composition of reported disabilities as the stigma around mental health issues fades to the wayside — which also neatly coincides with pandemic-era discussions around mental health.

Continued challenges for disabled workers

The tight labor market, access to remote work, and greater visibility during the pandemic may have helped labor force outcomes for disabled workers. But there still exist dramatic barriers to entry that the government needs to break down before disabled Americans have the same labor force opportunities as nondisabled Americans.

Whether implicitly or consciously, ableism often factors into nondisabled people’s views, meaning workers with disabilities have to work that much harder to disprove those preconceptions. During the hiring process, recruiters should be sure to check their implicit biases, as it could be unwittingly impacting the hiring decision.

Despite the ADA being three decades old, workplaces across the United States lack accessibility. Part of the reason advocates for disability rights pushed for remote work is that a lack of access can prevent a disabled individual from working at a company.

Government income can also be a barrier to entry. It often takes quite a bureaucratic lift for a disabled person to get Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI). As of August 2022, the average monthly benefit was $1,362 for disabled former workers. This meager benefit can be supplemented by earnings, but those earnings must not exceed $1,350 per month, or they will lose SSDI benefits. This cap, known as the substantial gainful activity (SGA) threshold, often traps disabled Americans into poverty. Losing benefits would be devastating, so disabled workers accept lower wages than they likely could receive.

These are just some of the many reasons Americans with disabilities may have difficulty finding work. Once they join the workforce, different barriers persist. On average, employed disabled workers earned just $0.74 on the dollar compared to nondisabled Americans in 2020.

Conclusion

Workers with disabilities have seen fairer labor market outcomes in recent years. The tight labor market opened employers’ minds and broadened recruiters’ techniques. The advent of remote work culture created new opportunities for historically sidelined workers with certain disabilities.

However, as labor market tides fall, disadvantaged workers are often the first to suffer. The gains made in recent years are fragile; disabled workers still face vast barriers to entry and obstacles of inaccessibility deeply ingrained into society. As the population of disabled Americans increases, and more than 30 years after the Americans with Disabilities Act, it may finally be time to consider how to properly bring this population into the labor force permanently, rather than as a benefit of a tighter labor market.

Maria Flores contributed to this article.