The labor market is entering a period of mild “stagflation” — a term popularized in the 1970s that describes an economic phenomenon in which weakening growth (stagnation) combines with elevated prices (inflation). But in this case it’s applied to just the labor market, and it seems to be a mild case looming, with no signs yet of a major labor market recession or wage-price spike. What that means for recruiters and talent acquisition (TA) leaders — the people who power hiring at major employers in the U.S. — is, well, more of the same. A slow-to-hire, slow-to-fire labor market; elevated wage growth; and a bifurcation between “standing up” and “sitting down” jobs. All major recruiting trends of the past three years will continue and perhaps be exacerbated by policy uncertainty — immigration restrictions, tariff volatility, Medicaid cuts, threats to Fed independence, and perhaps a government shutdown.

Labor market weakness is accelerating

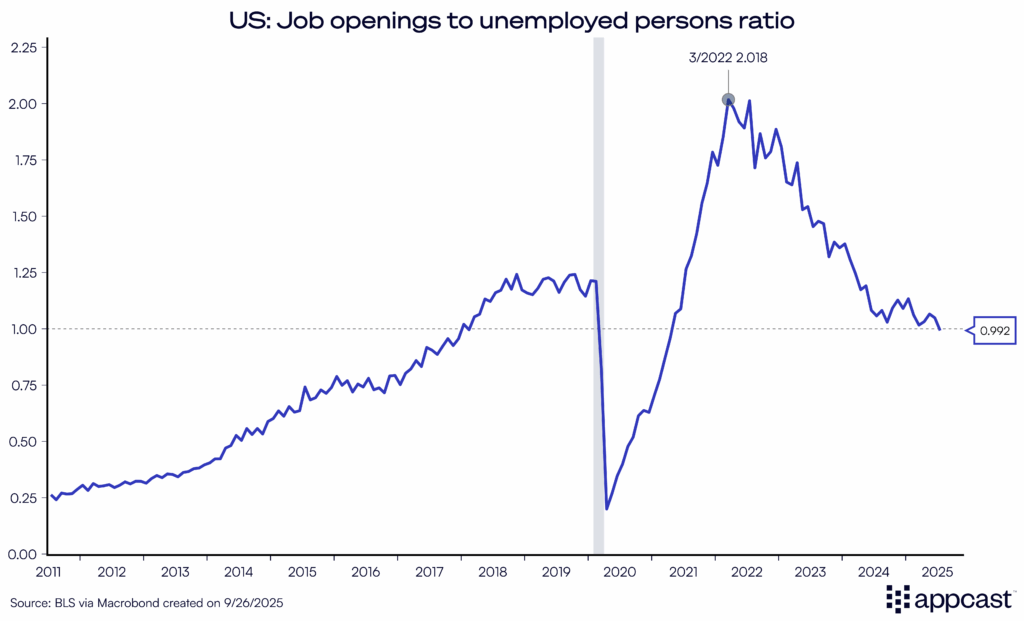

Labor demand has been cooling steadily, but the weakness is accelerating. Job openings hovered around 7.2 million in July and hires near 5.3 million — well below 2022 peaks — while unemployment has drifted up to 4.3%. Payroll employment gains slowed dramatically this summer, with just 29,000 jobs added per month in the three months ending in August. That combination — softer demand without a spike in layoffs — is classic late-cycle deceleration and implies longer times-to-fill easing in some categories but not universally (healthcare being the notable exception).

A symbolic marker was crossed in September: the number of unemployed individuals exceeded job openings for the first time since April 2021; but if you exclude the pandemic-era fluctuations, this goes back to February 2018. The driving factor behind this flip in the ratio is not a sudden surge in unemployment, but a steady decline in job openings — weakening hiring demand — since March 2022, which is coincidentally the month the Federal Reserve began to aggressively hike interest rates from near-zero levels.

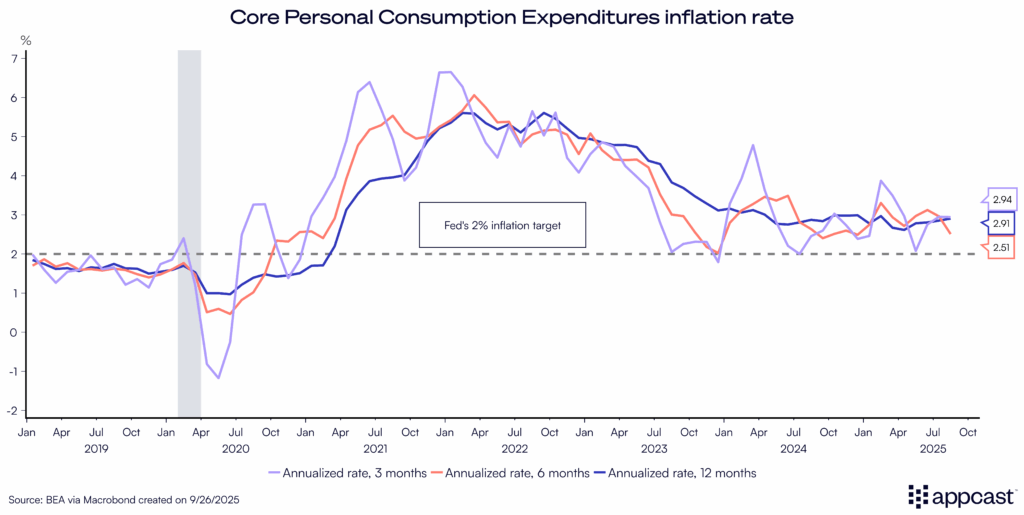

Inflation remains stubbornly above target

So, if that’s stagnation, what about inflation? The latest August inflation figures ticked up, stubbornly above the Fed’s 2% target. Earlier this week, Fed Chair Jay Powell noted that inflation progress has been uneven, while risks of “higher and more persistent inflation” remain, and interest rate cuts will respond to a “one-time increase in prices” from tariffs in a different way than if inflation remains an ongoing problem.

But inflation as it pertains to labor market dynamics means wage growth. Wage growth has been normalizing for three years. But the tariff-induced firming of overall inflation, plus the immigration restrictions that have not been fully enacted, mean upward pressure on wages looms for specific sectors. Which sectors — those which have thrived the most in recent years: healthcare and “standing up” jobs.

Sectoral bifurcation will persist

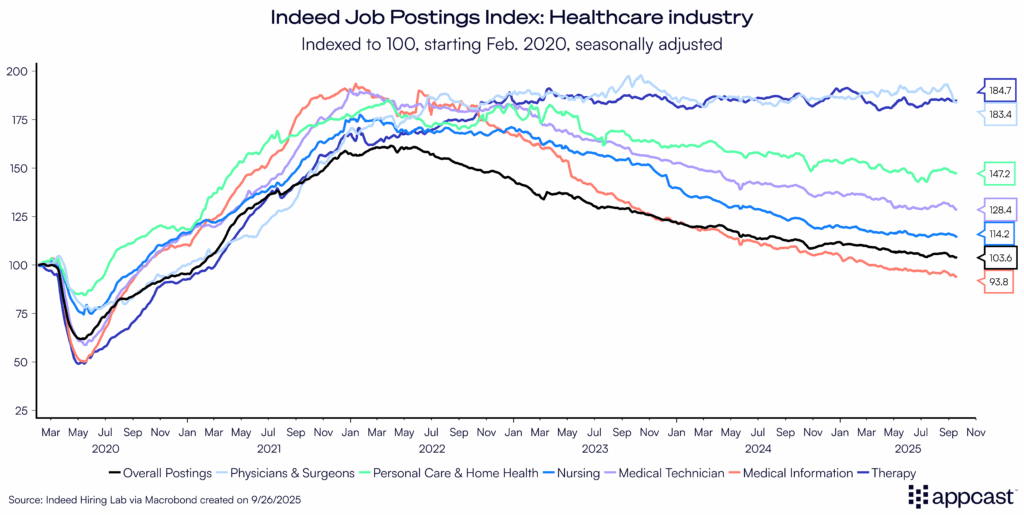

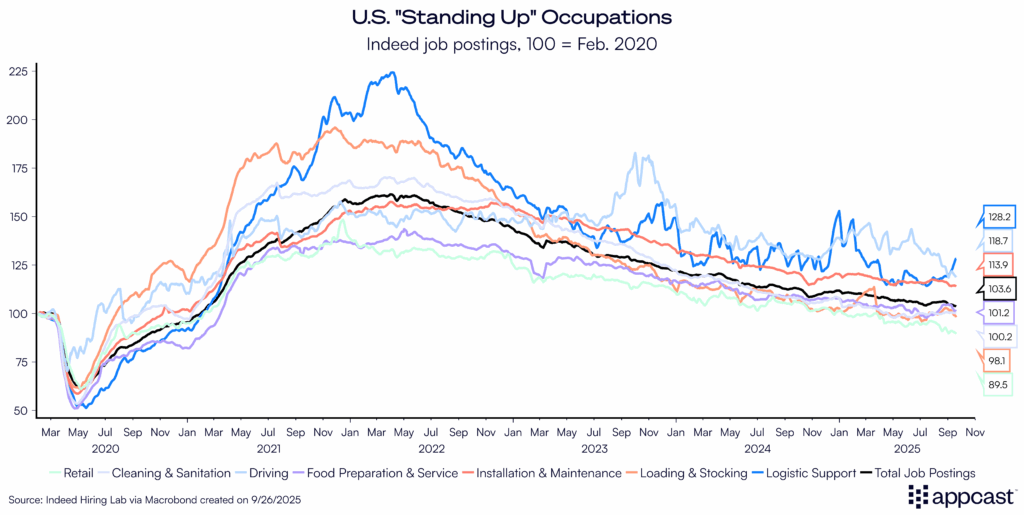

“Standing-up” work should remain comparatively resilient. Healthcare is still adding jobs (+47,000 in August) and is the central driver in the future hiring projections, reflecting aging demographics. Nearly all healthcare occupations have more job postings on Indeed today than the overall trend would project. With total job postings just 3.6% above Feb. 2020 levels, all but “Medical Information” have exceeded that.

Other standing up jobs are either thriving or down just modestly, according to Indeed data. Retail is perhaps the one big exception, with tariff effects clouding its outlook. Recruiting and TA leaders should expect continued scarcity in direct care, skilled trades, and site-based operations roles.

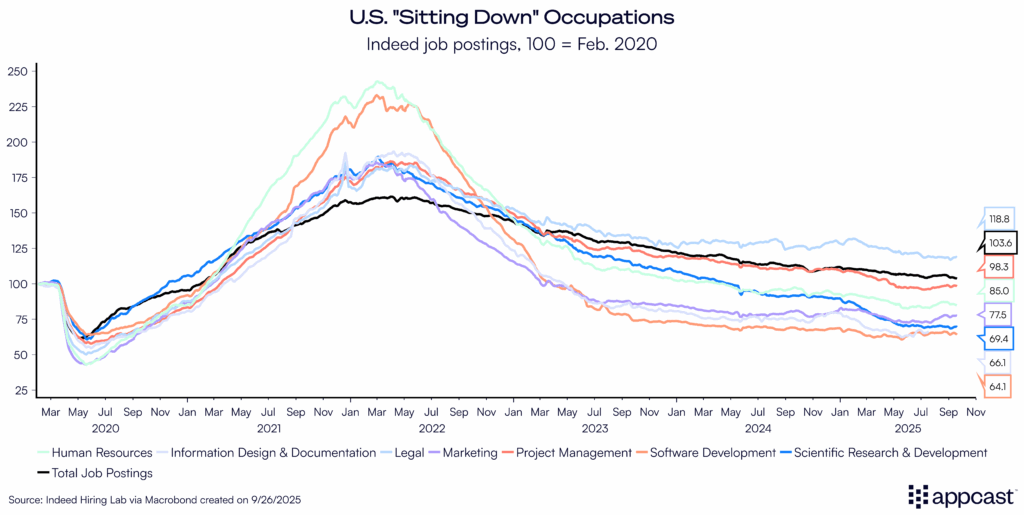

By contrast, many “sitting-down” categories (tech; professional & business services) face a slower hiring cadence as employers protect “unit economics” (aka profit protection), while AI-enabled productivity gains and higher capital costs curb incremental requisitions. Don’t bank on a rapid rebound here unless rates fall faster than the Fed currently signals.

Policy uncertainty points to stagflation

Economic policy uncertainties complicate hiring planning. First, there are tariffs. Tariff-related input costs — from steel and aluminum to automobiles and furniture — raise the odds that goods disinflation stalls or reverses into 2025–26, keeping overall inflation sticky even as growth cools. That dynamic can keep wage expectations firm, which presses CFOs to push for slower headcount growth. Recruiting and TA leaders should prepare for renewed compensation budget friction and find solutions for better hiring efficiency.

Then, immigration adds uncertainty. If policy or enforcement actions slow labor-force growth, tightness could persist in care, agriculture, construction, food processing, and logistics — sectors already reliant on new entrants — while macro demand remains soft. Treat supply risk as a possibility in workforce plans (pipeline building, cross-training, and internal mobility), even if the timing and magnitude are uncertain. We’ve covered the detailed repercussions of restricting immigration before. Ditto for looming Medicaid cuts from the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act.”

And then there’s threats to Fed independence and a potential government shutdown. The Supreme Court is taking up the case of whether Fed Governor Lisa Cook can be removed from her position by President Trump for “cause,” and what exactly counts as cause is disputed. Both potential sources of instability suggest political instability and polarization means U.S. government debt — long the bedrock of the global economy — is increasingly becoming suspect. Combined with the dire fiscal outlook, as Moody’s chief economist Mark Zandi has stated, it means they should plan for higher interest rates.

What does this mean for recruiters?

Mild stagflation does not mean a dire recession. Policy uncertainty alone — even a government shutdown, or further tariff surprises — may not push U.S. economic momentum into the red. After all, Q2 GDP rebounded to a robust 3.8% growth rate, and consumer spending through August has remained resilient. Job growth slowing indicates softening demand, but it just as well means the labor force is shrinking from immigration restrictions. In other words, what counts as a “good” jobs report is an increasingly smaller number.

But mild stagflation does mean weak hiring demand in “sitting down” occupations, combined with specific talent shortages in “standing up” jobs. Wage bargaining will be complicated, as well, as inflation remains above the pre-COVID baseline.

Translation for recruiting and TA leaders: significant Fed rate cuts aren’t baked into the forecast, barring an ugly turn toward recession. As financing conditions may stay tighter than hoped, hiring plans should assume a slower, bumpier environment. Mild stagflation and uncertainty are likely to mean lackluster hiring in 2026.