In a previous blog post, we discussed how the U.S. election will affect the German labor market. In this piece, we will discuss the effects of a Trump presidency on the U.K. Ironically, British deindustrialization, once seen as a major weakness that has negatively affected economic development in certain regions, might now be a relative advantage. As the U.K. has become a service-exporting superpower, its economy might be relatively unaffected from Trump’s tariffs.

Stagnant but with upside potential?

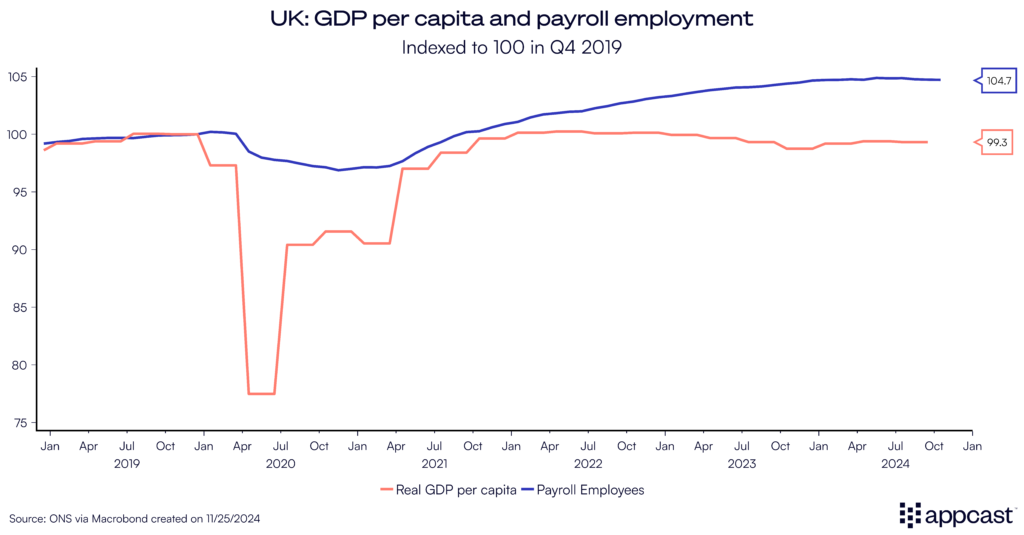

The U.K. economy has faced various headwinds over the last couple of decades. Austerity in the aftermath of the financial crisis was a big mistake, then Brexit probably shaved off about 4% from per capita incomes in the U.K. The recovery from the pandemic has been anemic as high interest rates to contain inflation have been constraining economic growth. Payroll employment growth initially surged throughout 2021 and 2022 but has also been completely stagnant this year. Per capita GDP is no higher than in late 2019.

The Autumn Budget from the Labour government is setting up the economy on a different path. Higher government spending and higher taxation are to be expected. The hiring outlook will remain challenging at first because of the increase in employers’ national insurance contributions and another minimum wage hike.

Nevertheless, economic growth in the U.K. has defied forecasts of a long and scarring recession. Relatively speaking, the U.K. has large upside potential if Labour were to finally fix the country’s most severe bottlenecks (housing and infrastructure).

Unlike continental Europe, the U.K. is uniquely positioned to come out of a potential trade war relatively unscathed. There is even a chance that the U.K. might indirectly benefit from some of Trump’s policies.

Not all of Europe will suffer equally

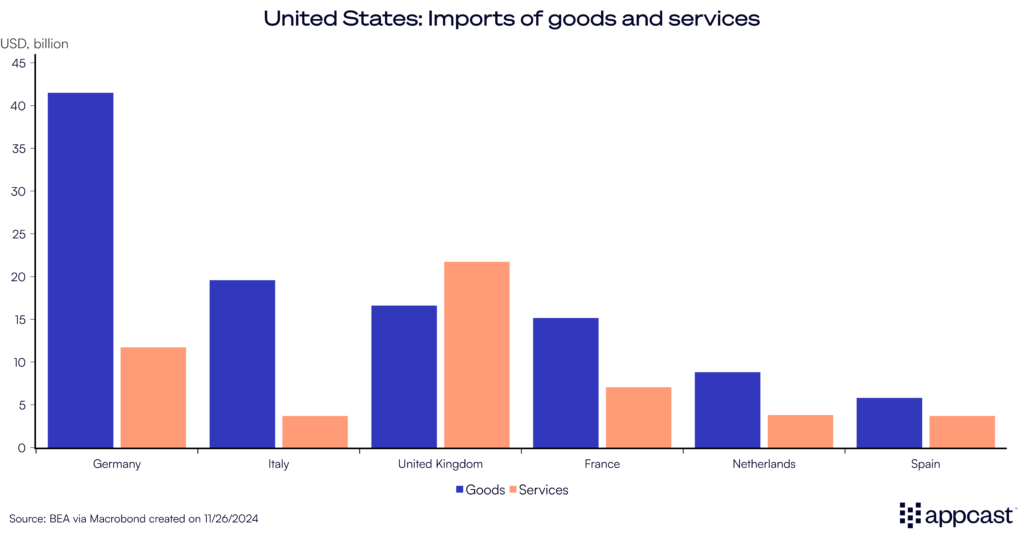

Not all European economies are equally vulnerable to Trump’s policies. Germany’s large export exposure means its economy will suffer the most from a trade war. Other large EU countries like Italy, France, and the Netherlands also export a lot to the U.S. and will be negatively affected by tariffs.

The U.K. economy, on the other hand, is more immune for two reasons. First, Trump has already mentioned that he might give the U.K. a special trade deal. Second, the U.K. has become a service superpower and nowadays exports more services than goods to the U.S. (close to $90 billion compared to about $65 billion).

A big share of British exports is immune from tariffs

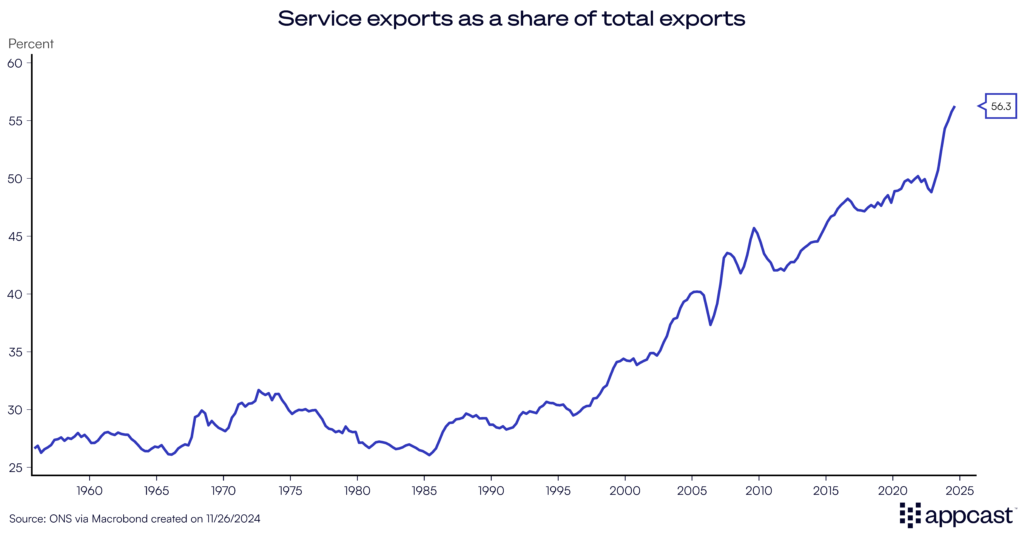

In fact, more than 55% of the U.K.’s exports to the rest of the world are services. As a point of comparison, for most other advanced economies, such as France, that value stands closer to 30% or even lower (about 20% for Germany). And since there are no physical goods crossing borders, service exports are not subject to tariffs.

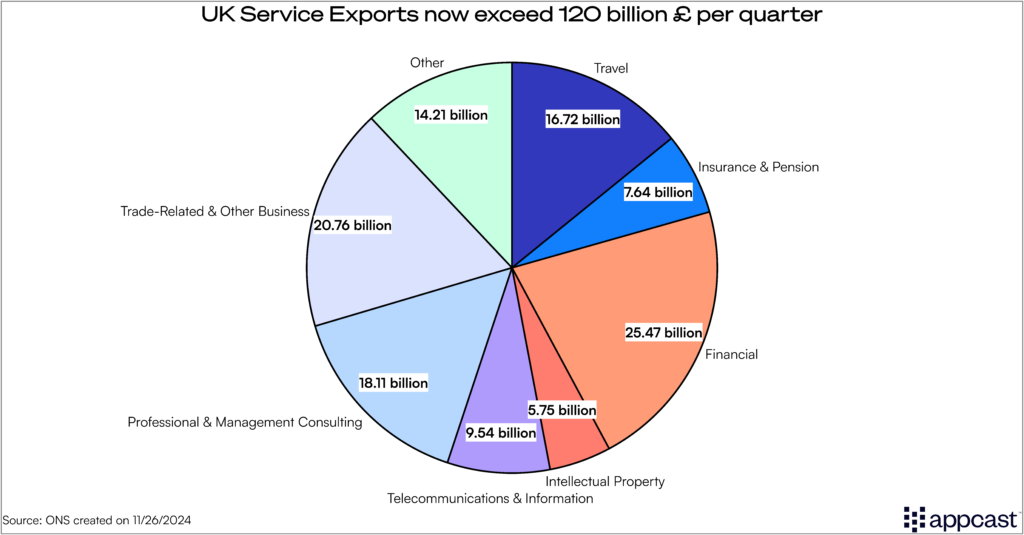

The pie chart below breaks up the U.K.’s service exports into different categories to give you an idea of what we are talking about.

£25 billion in quarterly exports to the rest of the world are coming from the financial sector. This includes Fintech solutions (using Revolut or Wise for cross-border payments), investment banking services, asset management, merger and acquisition advisory services, etc. Some £18 billion are coming from professional and management consulting services. Accounting and auditing services are another big U.K. export. And £17 billion comes from travel (tourism is classified as an export).

A special deal?

The U.K. economy with London at its center is basically an island of lawyers, bankers, and consultants who are offering their services to clients abroad. All these activities have become economically more meaningful than the exports of actual goods, which has completely stagnated in recent years due to Brexit. The fact that the U.K. has become a service-exporting superpower is now playing to its strength since these activities will be exempt from Trump’s tariffs.

A special trade deal between the U.S. and the U.K. also seems to be in the cards, which would provide a boost to the U.K. economy. It would penalize imports from Europe and divert trade via the U.K. Some companies would choose to import goods from the EU to the U.K. and make marginal adjustments there: light assembly, minimal processing (adding final components and superficial manufacturing steps), and repackaging. This would then allow the goods to be re-exported to the U.S. While trade diversion would make the U.S. and Europe poorer, it could provide a boost to the U.K. as some economic activity related to these trade flows would be relocated here.

A stronger dollar is perilous for global growth

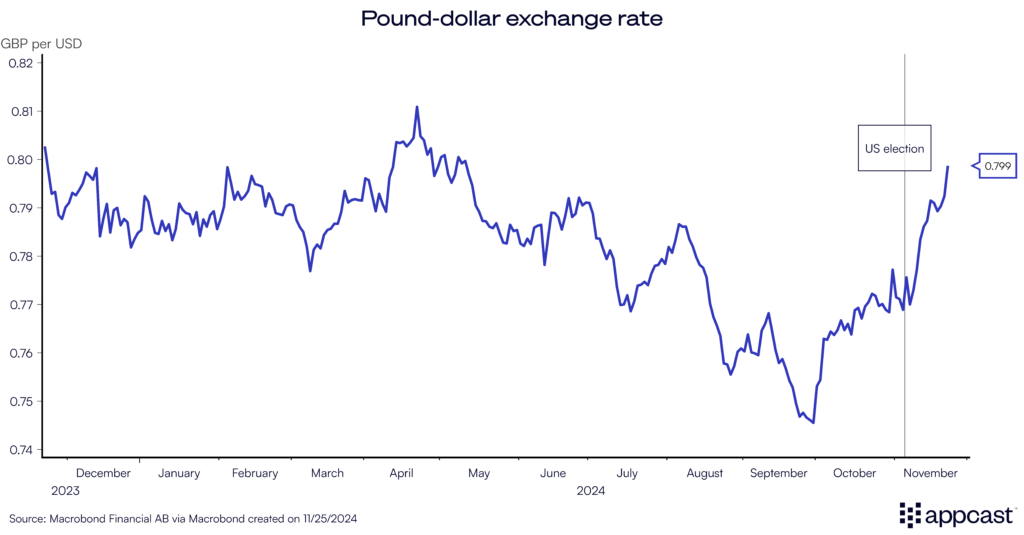

But even as the U.K. service exports are sheltered from tariffs, the economy may still suffer due to the international role of the dollar. Many of Trump’s economic policies are inflationary in nature, meaning higher U.S. interest rates.

The dollar has already appreciated against all currencies following the election and is expected to see further gains. A lot of international trade is invoiced in dollars. Furthermore, many countries, global corporations, and even households use the dollar as a funding currency and store of wealth.

Economic research suggests that a rising U.S. dollar is contractionary for the global economy because goods invoiced in dollars become more expensive and because borrowing costs of households and corporations with dollar debts increase. Estimates show that a 10%-dollar appreciation can shave off 1.5% real GDP growth in emerging markets and 0.5% growth in advanced economies in the first year, with some further smaller economic losses spread out across the two subsequent years.

A stronger dollar could force the Bank of England into keeping interest rates higher for longer because of inflationary pressures coming from commodity prices (usually invoiced in dollars). This, in turn, would lead to more sluggish growth and inhibit job creation.

Geopolitical shocks

Another big concern for the U.K. and Europe in general under a Trump presidency is the de-escalation of geopolitical shocks. It is unclear to what extent the new U.S. administration will continue to support Ukraine. A Russian win would be terrible news for Europe’s economy. Military spending could rise, with the aim to deter further Russian aggression; that spending would come at the expense of necessary funding elsewhere. This will be particularly true for the U.K., which already has very little fiscal space to begin with and pays relatively high interest rates on its debt.

Geopolitical shocks are inflationary in nature and therefore bad for economic growth. Higher commodity prices or supply chain disruptions drive up prices, leaving the BoE with no choice other than to leave interest rates higher for longer. Tight money is felt across all sectors, depressing business investment and household spending, which would have detrimental effects on the labor market and hiring outlook.

What does that mean for recruiters?

The effects of Trump’s presidency will be felt unevenly across Europe’s economies and labor markets. Germany’s economy is the most vulnerable to tariffs due to its high reliance on manufacturing and the export sector. Other large exporting nations like the Netherlands will also feel the pinch.

While the U.K. will also be affected by geopolitical shocks and the appreciation of the dollar, its economy will likely turn out to be more resilient to Trump’s trade policies. First, Trump seems to be willing to renew the relationship between the two countries and might give the U.K. a deal. Second, the U.K. and the city of London have become a global service hub. More than half of the country’s exports are now services which will not be subject to tariffs. The U.K. will therefore be more immune from tariffs as the export of actual goods has become secondary. Policy makers in the U.K. should therefore focus on the country’s competitive advantage in service exports.

In terms of the hiring outlook, it is too early to tell how the different U.S. policies will play out. The stronger dollar is a negative for the U.K. economy, as are tariffs applied to the exports of goods. A special trade deal between the two countries, on the other hand, would come at the EU’s expense and might provide the U.K. economy and labor market a well-needed boost.