Despite Brexit, the U.K. has recently seen a surge in inward migration with non-EU nationals more than making up for the negative net outflow of EU nationals since 2020. The U.K. will remain a popular immigration destination, but the housing market and public infrastructure remain key constraints.

- Emigration means to leave one’s country to live in another.

- Immigration is to come into another country to live permanently.

- Net migration: Number of immigrants minus the number of emigrants (inflow – outflow).

The UK has been a popular immigration destination for decades now

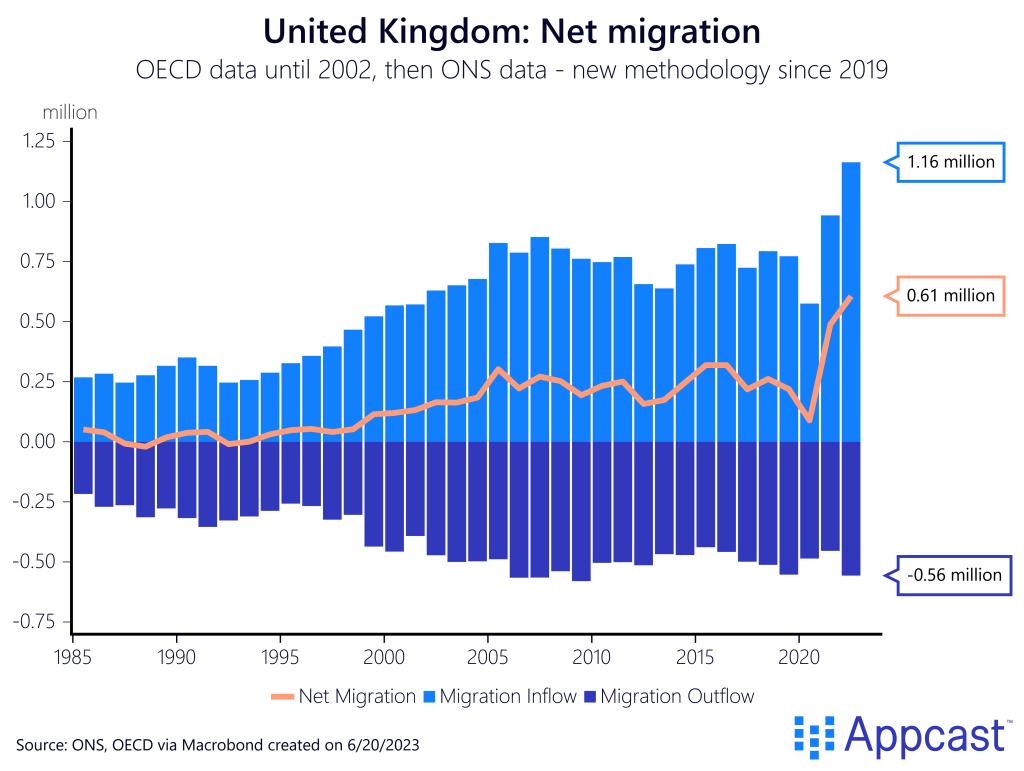

The U.K. was a country of emigrants for a very long time due to its colonial history. British citizens settled in countries like Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and the U.S, among others.

In the first half of the 20th century, net migration was substantially negative with about 80,000 more people leaving the U.K. than arriving on annual basis between 1900 and 1930.

The foreign-born population thus remained at relatively low levels and only started to pick up after World War II when the British Nationality Act allowed all citizens of British colonies to move to the U.K., which led to an inflow of migrants from Jamaica and Africa.

Due to popular opposition to more immigration, the U.K. government gradually tightened control on immigration in the early 1960s, which led to a decline in net migration in the following decades.

While net migration was still relatively low in the 1980s, it picked up markedly in the 1990s and 2000s. The Tony Blair government eased migration restrictions and the U.K. was one of only three countries in the European Union, together with Ireland and Sweden, that didn’t allow transitional controls of migration coming from the ten Eastern European countries that joined the EU in 2004.

This liberal policy played a big role in boosting the number of foreign-born residents in the U.K., which increased from about 8% in the 1990s to more than 14% today. With the Eastward expansion of the EU, a few hundred thousand workers (many of them coming from Poland) arrived in the U.K. in search of better living standards and higher wages.

As such, net migration to the U.K. increased from close to zero in the early 1980s to an annual inflow of more than 200,000 in the 2000s and 2010s. According to some estimates, the number of Poles in the U.K. approached one million in 2017 but has fallen by several hundred thousand over the last couple of years. Obviously, Brexit plays a big role here, but Polish living standards have also improved to such an extent over recent decades that its income level is now exceeding Portugal’s and Greece’s GDP per capita and will continue to converge with Italy and the U.K. in the coming years.

During the height of the pandemic, net migration went down significantly but has now increased to new record highs in 2021 and 2022 with more than 610,000 people settling in the U.K. last year alone, significantly more than was estimated by the Bank of England.

It should be noted though that in 2019, the ONS changed the methodology of how it counts net migration. The data points collected since then are preliminary. While they also have been subject to revisions, they are the most accurate estimates currently available.

Brexit didn’t reduce but significantly changed the composition of migrants

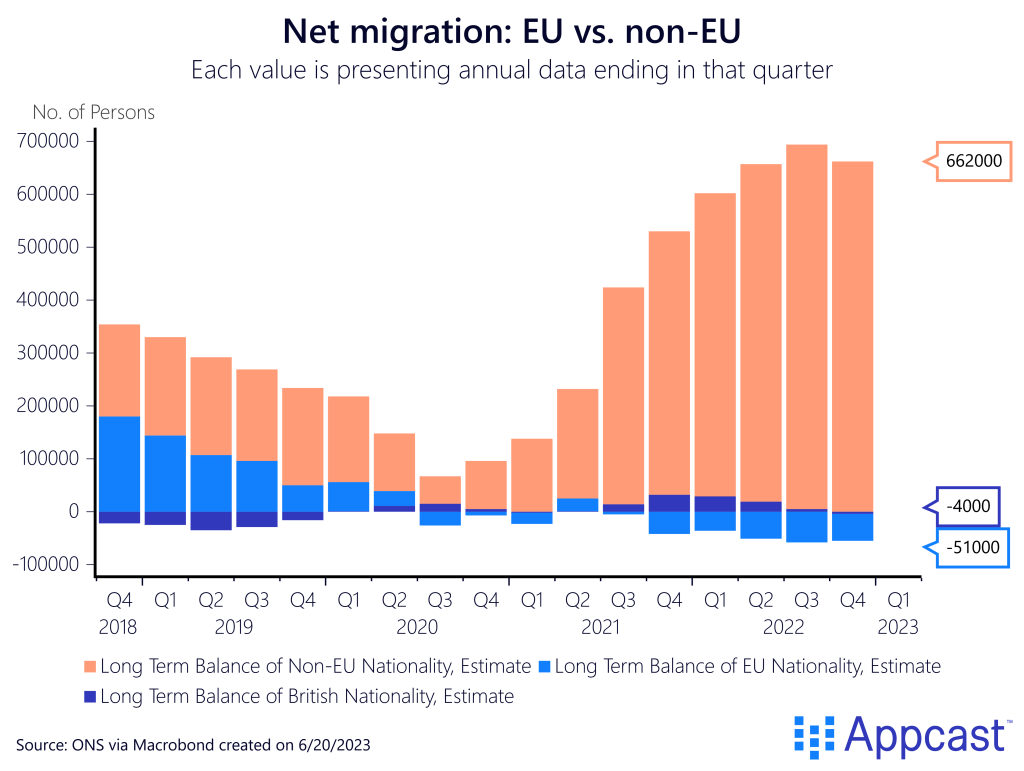

While it is fair to say that Brexit was, to some extent, a vote against migration, the outcome has been different than what most people probably expected, given the record inflow of immigrants over the last two years.

As the following chart shows, the composition of immigrants has shifted significantly because of Brexit. The entire addition to the current immigrant population in the U.K. is coming from outside of the EU. In fact, net migration from EU countries has been negative since 2020. Last year alone, some 50,000 EU citizens left the U.K. while a record of 660,000 non-EU citizens arrived.

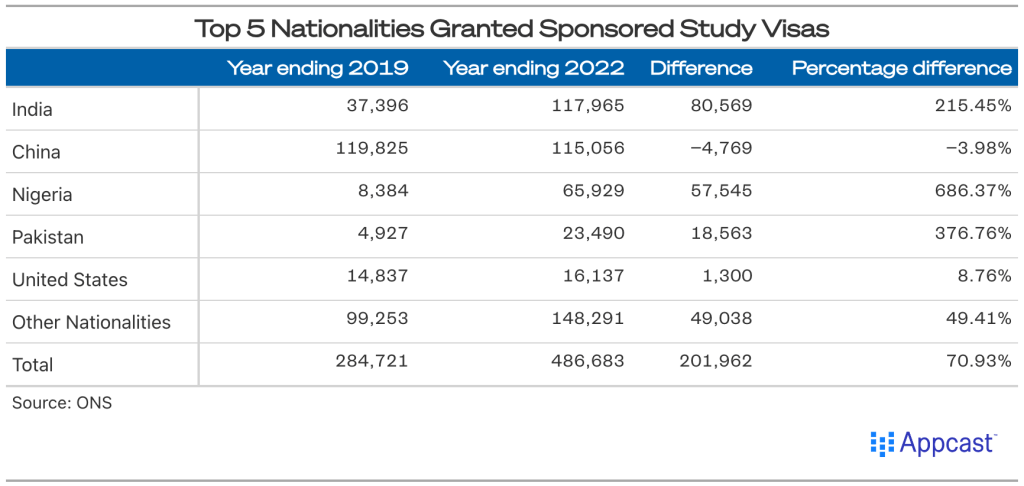

Looking at immigration by type, the most significant increase has been the increase in the number of students, which almost doubled in 2022 compared to pre-pandemic levels. The number of foreign students has never been as high in the U.K. as it is right now – some 680,000 in the academic year 2021/2022.

The number of granted student visas for Indians has increased by an impressive 215% compared to 2019 and now stands at close to 120,000. There are also more than 115,000 and 60,000 visas granted to Chinese and Nigerian students, respectively.

The number of persons coming for humanitarian reasons has also seen a recent vast increase – shown as “Other Nationalities” in the chart above – from about 50,000 pre-pandemic to five times as much last year. A lot of the inflow is related to the political turmoil in Hong Kong and the war in Ukraine, which has displaced millions of people.

The number of work visas has increased from about 150,000 pre-pandemic to almost 300,000 at the end of last year. Both student visas and work visas included dependents. For study visas, the number of dependents last year was less than 20%, whereas for work visas the number of dependents was about one third.

The UK’s long-run demographic outlook

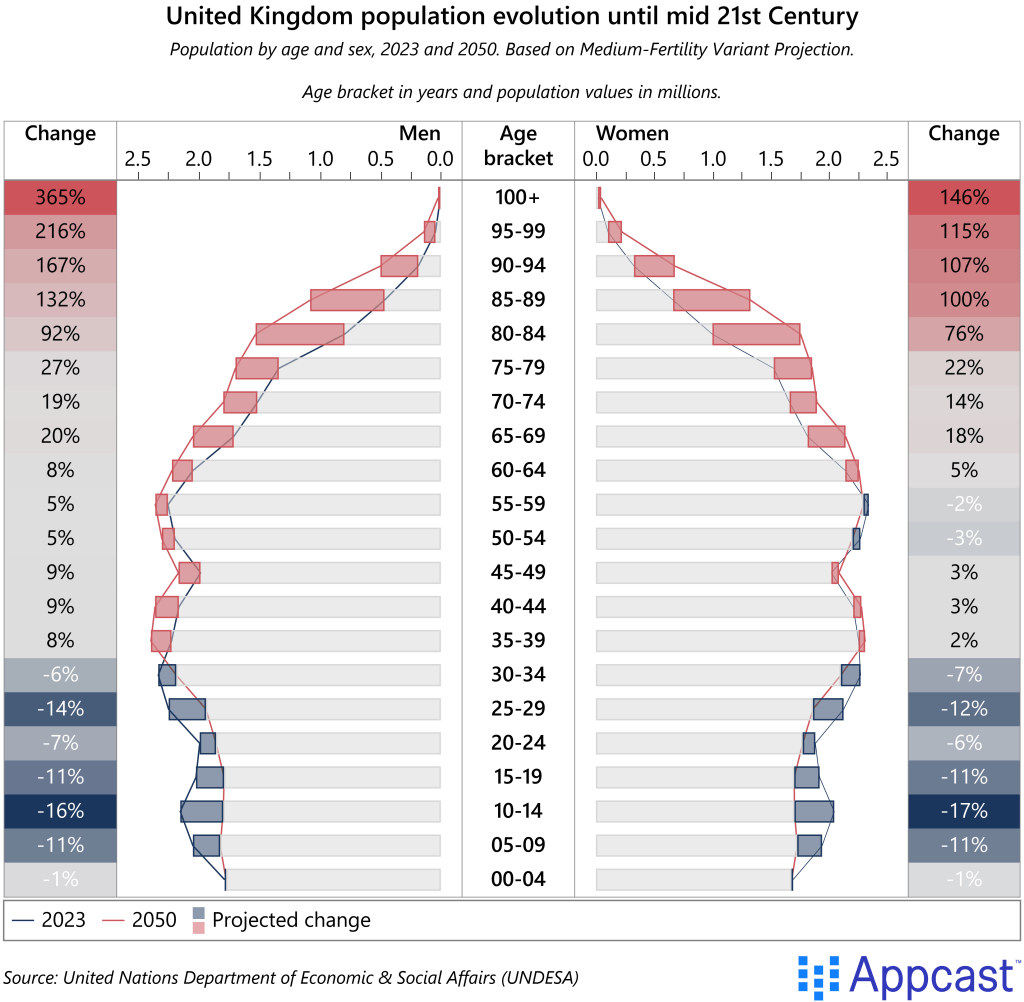

Similar to other advanced economies, the U.K.’s long-run demographic outlook is challenging. Current population projections foresee a massive demographic shift with the number of old-aged persons increasing a lot in the coming decades while the younger generation will see a decline in numbers due to low fertility rates. The number of people approaching retirement age might increase by as much as 20% between now and 2050, while the working-age population will stagnate or even shrink.

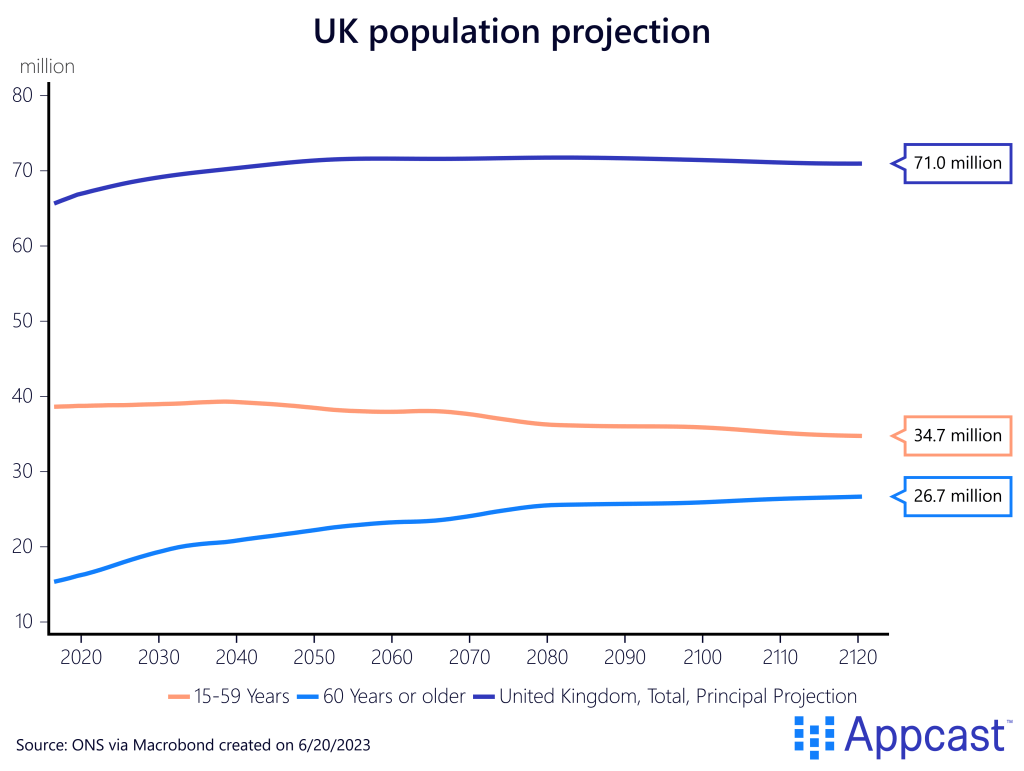

ONS long-run projections suggest that the U.K. population will peter out at a little over 70 million a decade from now and then stagnate. The working age population will reach 40 million in the next few years and shrink from about 2035 onwards.

These long-run demographic projections are, of course, highly uncertain. While birth rates are a slow-moving variable that changes slowly, economic events like the Global Financial Crisis and COVID have pushed down fertility rates in advanced economies even further.

The biggest unknown to the long-run demographic outlook is migration. More liberal migration policies in advanced economies could undo the population decline that seems to be baked in right now. This would, to some extent, come at the expense of developing economies, many of which will face a stagnating or declining population soon enough themselves.

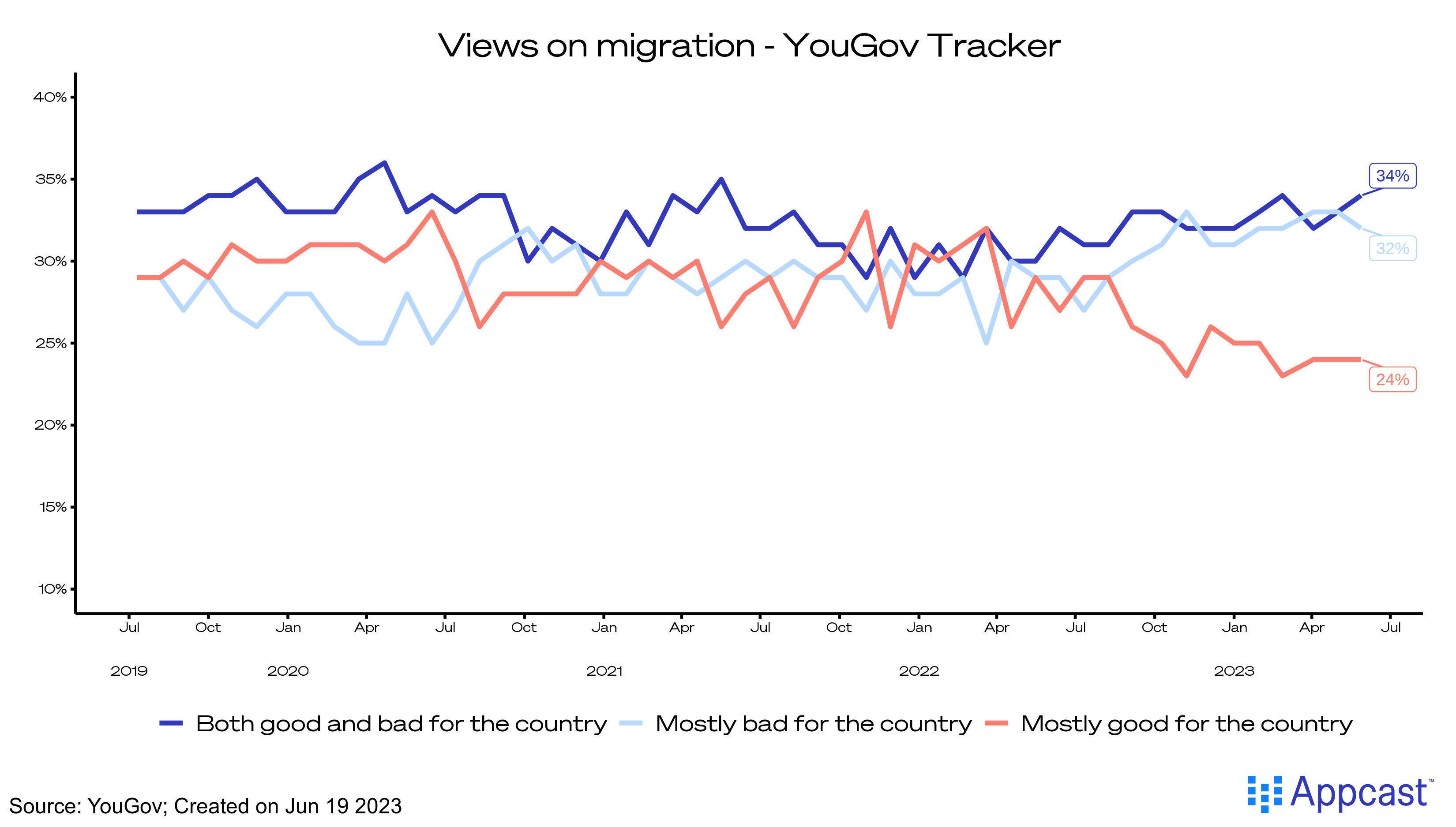

Given how the U.K. economy has been struggling over the last few years, it is maybe not that surprising that negative views on migration are holding steady. A monthly YouGov tracker shows that the percentage of people who think migration is mostly good for the country has declined from about 30% to about 25% over the last year. At the same time, a slightly increasing share view migration as mostly bad or have mixed feelings about it.

These negative sentiments towards immigrants will only change if policy makers address all the issues the U.K. is currently facing in terms of housing, health services, and public infrastructure in general.

Conclusion

The U.K. is one of the advanced economies that is the most affected by the cost-of-living crisis, and this is particularly true when it comes to housing. It is thus no surprise that sentiment towards immigration is not exactly positive. U.K. residents understand that letting more people in will put additional pressure on the housing market and public infrastructure.

At the same time, more immigration is desperately needed to increase economic growth and address debt and pension-sustainability issues. Moreover, skilled workers are needed to solve the current labor shortages that many U.K. employers are facing.