The global labor shortage is intensifying

Adverse demographic developments across advanced economies mean that the global labor shortage is going to intensify in the coming years. Some countries, like Germany, are seeing their labor force already shrink right now. While demographics for the U.S. are more favorable, net migration has fallen a lot over the last few years and adding to the problem, even as the numbers are currently recovering.

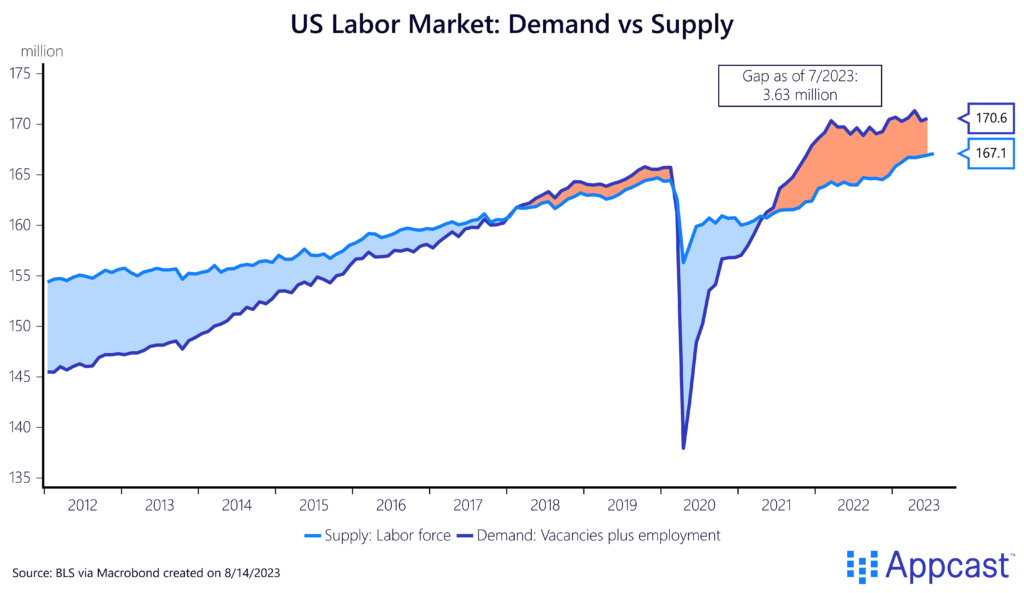

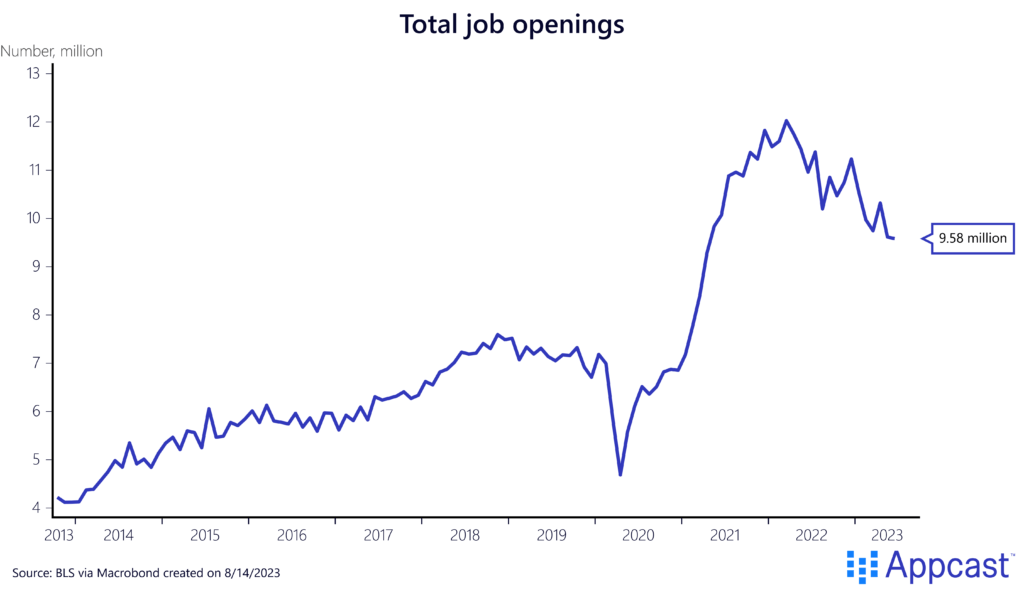

The U.S. labor market is the hottest in decades with unemployment at a record low and prime age labor force participation being at its highest since the early 2000s. According to our estimates, U.S. labor demand – proxied by total employment plus vacancies – is outstripping the labor supply by more than 3 million. And this will continue to put upward pressure on wage growth for the time being.

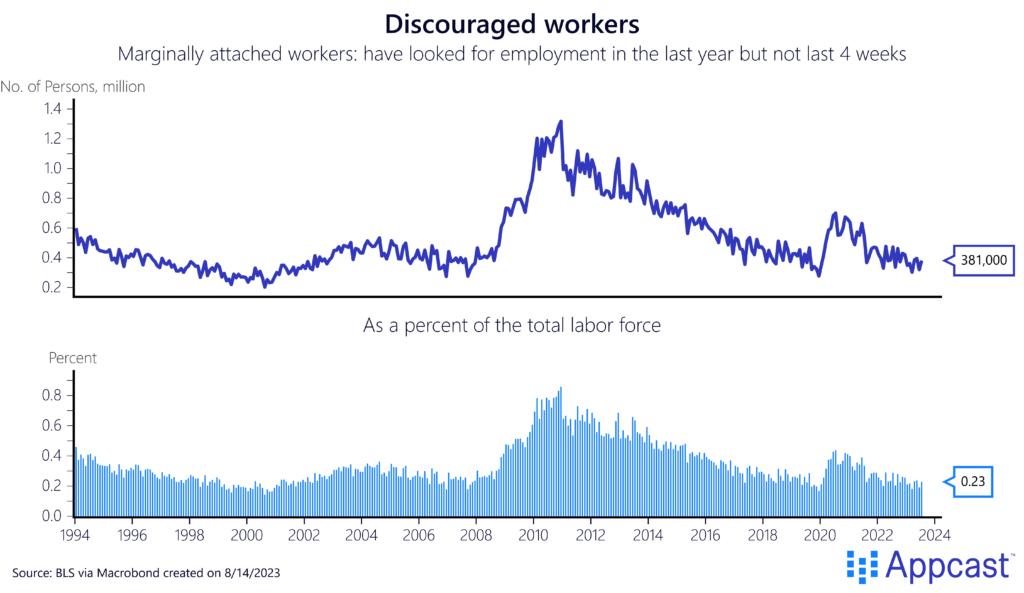

Thanks to the very tight labor market, the total pool of available workers on the sidelines has decreased quite significantly. The unemployment rate has been below 4% for almost two years now. The total number of marginally-attached workers – persons who had been looking for a job over the last year but not over the last four weeks – is also extremely low, especially when being measured as percentage of the total labor force.

This means that companies are struggling to tap into a pool of workers who are currently idle. Instead, recruiters are increasingly hiring from the employed rather than from the shrinking cohort of unemployed and marginally-attached workers.

More poaching is happening

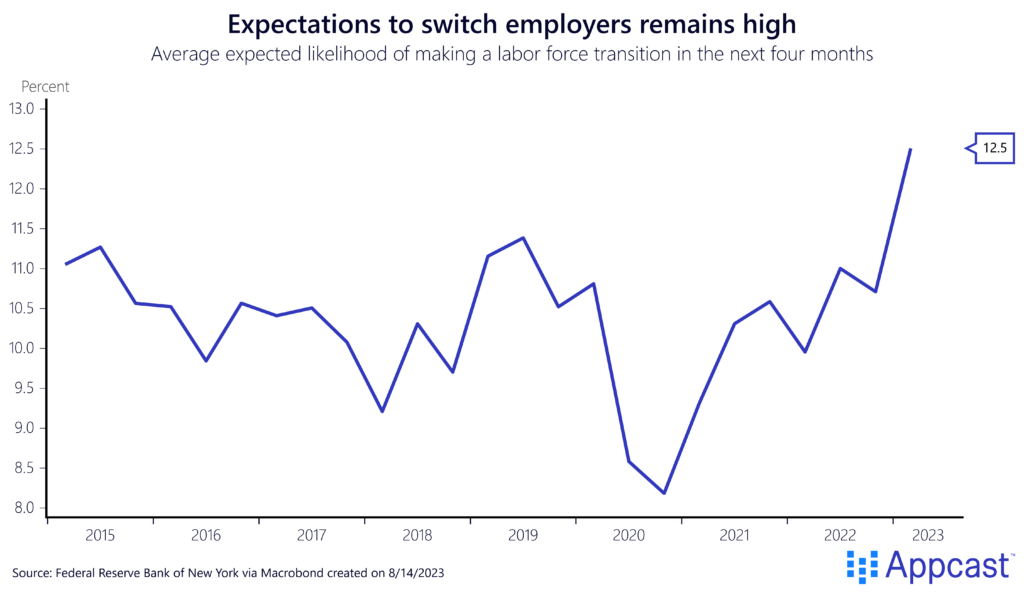

Surveys confirm that this poaching is now happening more frequently than in the past. A consumer survey from the New York Fed shows that expectations of job transitions to a new employer have reached an all-time high of 12.5% in early 2023. This is significantly higher than during the pre-pandemic years when the value fluctuated around 10%.

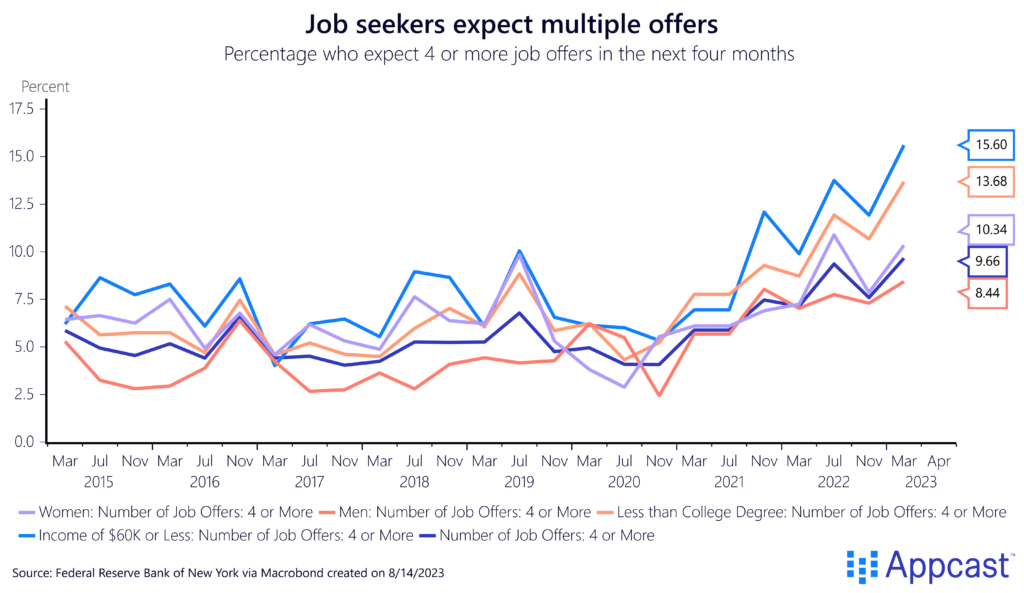

An increasing number of job seekers are reporting that they expect multiple job offers in the near future. The Fed survey shows that the number of job seekers who expect four or more job offers in the next four months has doubled for certain groups: 10% of women and about 8.5% of men expected more than four job offers in early 2023, up from about 7% and 4% in 2019.

Interestingly, the survey shows that the hot labor market is highly beneficial for low-skill workers. More than 13% of job seekers without a college degree and more than 15% of workers with an income below $60,000 currently expect more than four job offers, up from about 7% for both groups in 2019.

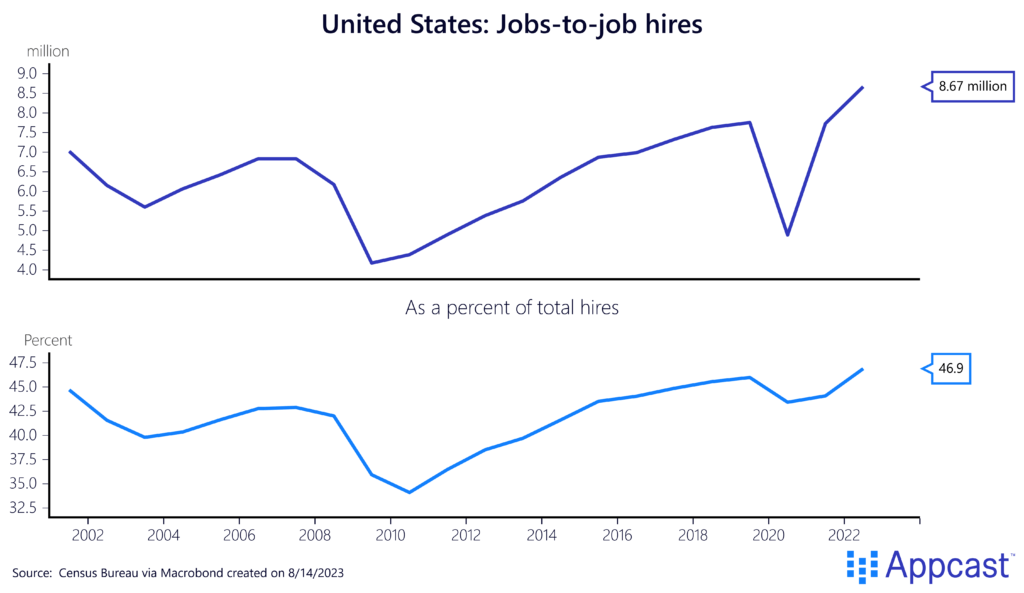

Data from the Census Bureau shows that job-to-job transitions have increased substantially in recent years, especially when compared to the weak labor market after the 2008 financial crisis.

Quarterly job-to-job hires increased to 8.5 million in late 2022; whereas, it was just over 4 million in 2009. As a percentage of total hires, job-to-job transitions increased to a record-high of more than 46%, compared to a low of 34% in 2009.

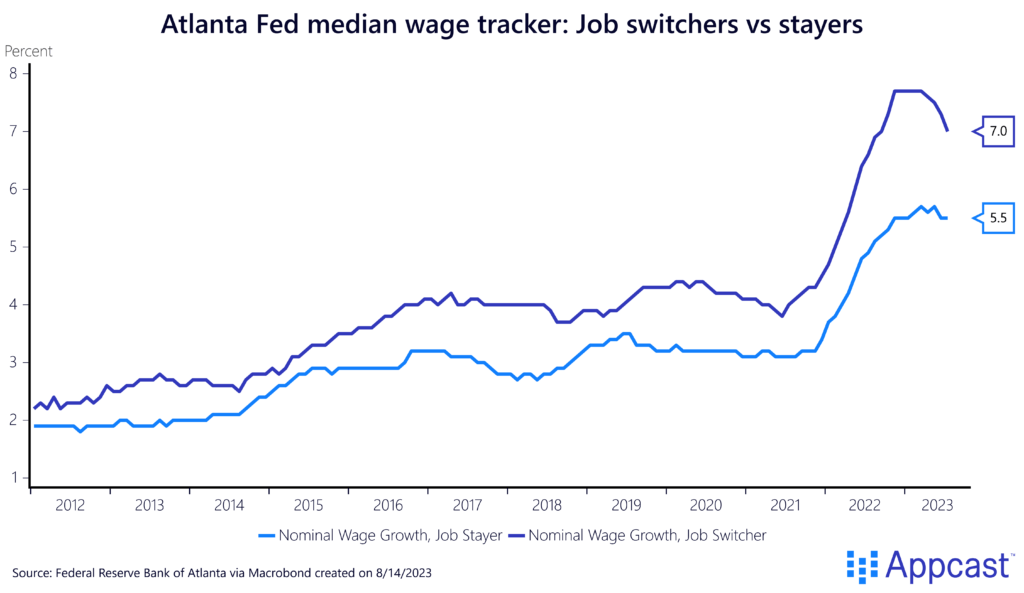

Wage data from the Atlanta Fed shows that switching jobs is also good for your wallet. Wage growth for job switchers has been significantly higher than wage growth for workers who stayed put during the pandemic.

The poaching economy has implications for the Beveridge curve

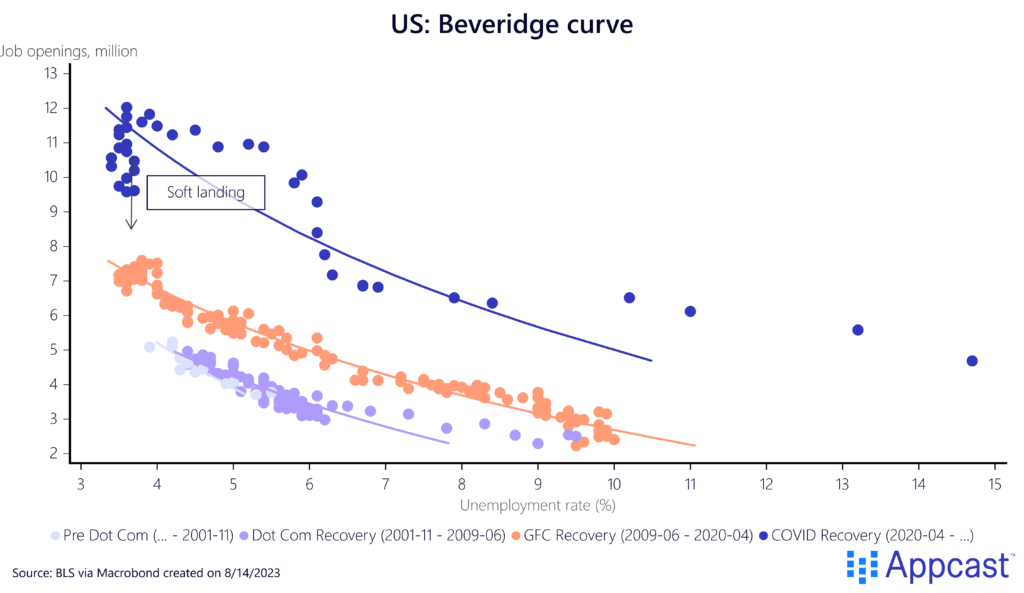

Economists refer to the relationship between the unemployment rate and job openings in the economy as the Beveridge curve. Usually, a higher unemployment rate comes along with lower job openings in a weaker economy, which is why the Beveridge curve is downward sloping.

An upward shift of the Beveridge curve means that the labor market has become more inefficient. There are more open vacancies for the same unemployment rate, therefore matching in the labor market has deteriorated. Employers now need to post more open positions than before for any given unemployment rate.

As the graph below shows, the pandemic has led to an unprecedented upward shift in the Beveridge curve. The precise reasons are still being debated. But it increasingly looks like the overheated economy in 2021 and 2022 created a surge in labor demand (i.e. open vacancies) that the dwindling pool of idle workers was unable to fill.

What does that mean for the labor market and a soft landing?

In retrospect, it is now quite clear that the U.S. economy was overheating in 2022 and that nominal demand was excessive. The very tight labor market has also been putting upward pressure on inflation. The Fed has increased interest rates over the last year to now 5% to cool down the economy.

Based on the historical relationship shown above, some economists argued last year that a soft landing would be unlikely. They suggested that the Fed would not be able to bring down vacancies (labor demand) without creating a significant increase in unemployment, thus moving down the Beveridge curve.

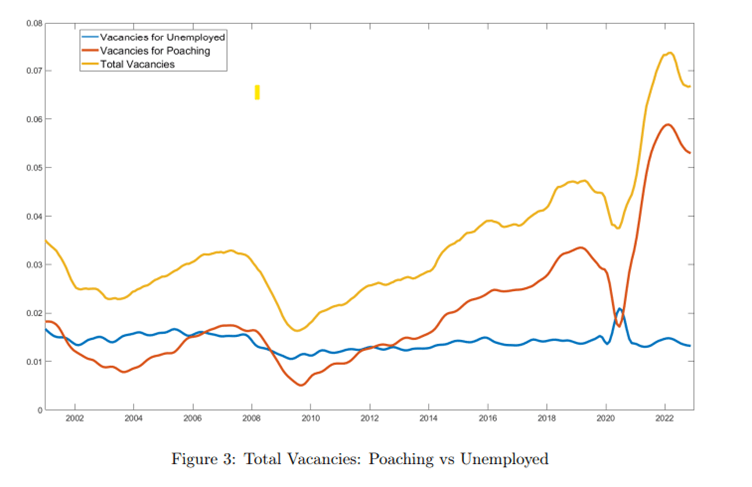

However, a recent paper by the St. Louis Fed disputes this argument. Their model shows that almost the entire increase in vacancies over the last couple of years is the result of an increase in vacancies for poaching rather than vacancies for the unemployed. Ultimately, that means that the Fed could cool down the economy without creating additional unemployment. With a cooling market, businesses would just substantially decrease their poaching vacancies at first, and unemployment would remain low.

Source: “The Dual Beveridge Curve” by Anton Cheremukhin & Paulina Restrepo-Echavarria

In terms of the Beveridge curve depicted above, a soft landing is becoming more likely if the Beveridge curve is very steepand it increasingly looks like that is the case! Total vacancies in the economy have already started to normalize and unemployment has not been affected. This is a significant win for the Fed as it increasingly looks like they can achieve a soft landing – a gradual cooling of the economy and labor market without creating a recession.

Conclusion

The labor shortage in the U.S. has important implications for how the labor market works and by extension, how monetary policy affects the economy. As the pool of idle workers has continued to shrink, recruiters are increasingly hiring workers that are already employed. In this poaching economy, a much higher share of job vacancies is for poaching than for targeting the unemployed. This means that the Fed can currently cool down the economy without having to create a recession because the Beveridge curve is much steeper. A cooling labor market will lead to a fall in job vacancies – the ones that are for poaching – while leaving the unemployment rate unchanged. This is exactly what we are seeing right now, which means that the odds of soft landing have increased substantially.