The natural rate of unemployment is a key economic variable used by the Federal Reserve to assess the stance of monetary policy and economic growth. The natural rate of unemployment is the unemployment rate that is consistent with price stability – defined as 2% inflation – and the economy growing at full capacity.

In contrast to the actual unemployment rate, the natural rate of unemployment cannot be observed directly, but it is instead estimated using macroeconomic models. The assumptions that go into these models are questionable and there is also in general quite a bit of uncertainty about the estimates.

Despite the uncertainty, the natural rate is of extreme importance when it comes to the economy because the Fed is paying so much attention to it.

To quote Paul Krugman: The unemployment rate in the economy is mostly where the Fed wants it to be, plus or minus a random error term, reflecting the fact that the Fed is not quite God.

And Krugman is basically right. Monetary policy determines more or less the aggregate pace of job growth in the U.S. economy during normal times. So, where the Fed believes the natural rate of unemployment to be matters a lot for millions of job seekers. That is why this rather wonky term is so important.

This becomes extremely obvious when examining the period following the Great Recession. Remember that the unemployment rate shot up from about 4% before the financial crisis to a peak of 10% during the recession. Many policy makers believed in the years following the downturn that the natural rate of unemployment had increased. A lot of people proclaimed that there was massive skill gap in the labor market. Some economists cited structural reasons for the unemployment rate being so high, a mismatch between the skills of jobseekers and what employers were actually looking for. Even more curious, video games were blamed too.

Ultimately, all of these reasons turned out to be wrong, as many neo-Keynesian economists argued at the time. The fundamental reason for high unemployment was weak demand, nothing else. The recovery from the Great Recession was super sluggish and it took years for the labor market to go back to normal. Then, during the Trump administration unemployment dipped below 4% again, thus hopefully putting to rest the claim that post-2008 high unemployment was structural.

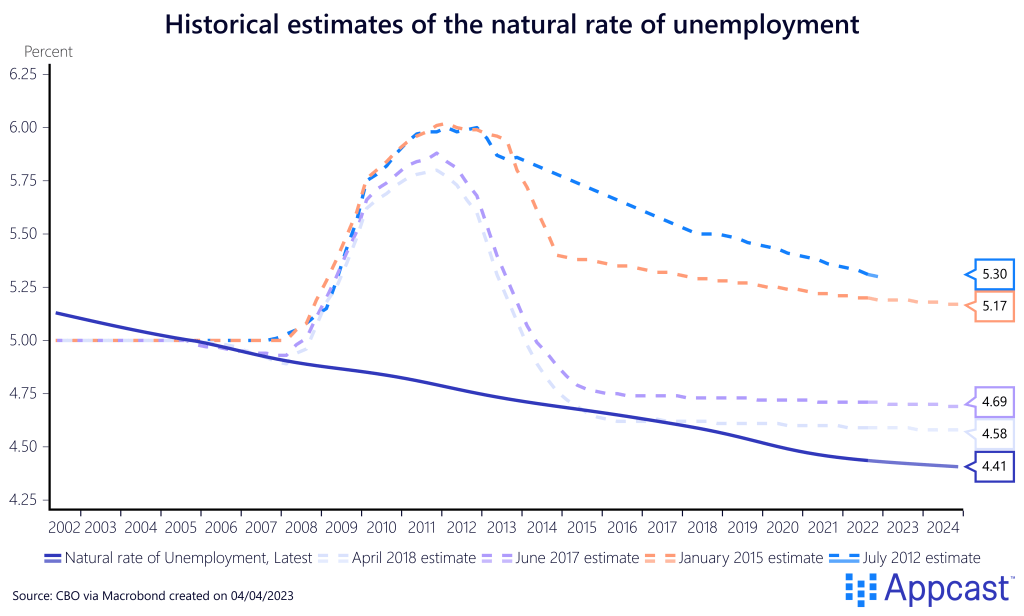

Even the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and the Fed thought at the time that the natural rate of unemployment had increased, though. The following chart compares old estimates for the natural rate together with the newest estimate for that series.

The 2012 estimate shows that the CBO thought at the time that the natural rate of unemployment increased all the way to 6% and that it would remain elevated for more than a decade. They subsequently revised down that estimate several times in the following years as the labor market recovered better than anticipated and actual unemployment went down.

Sorry, we were wrong!

The most amazing thing about that chart is that the CBO now retrospectively changed their opinion completely in 2022 about where the natural rate was after the financial crisis.

The revised 2022 estimate from the CBO now shows that the natural rate didn’t increase at all post 2008. While this admission of “Oops, we were wrong. Sorry!” is certainly applaudable, that mistake had real-life implications for hundreds of thousands of jobseekers at the time.

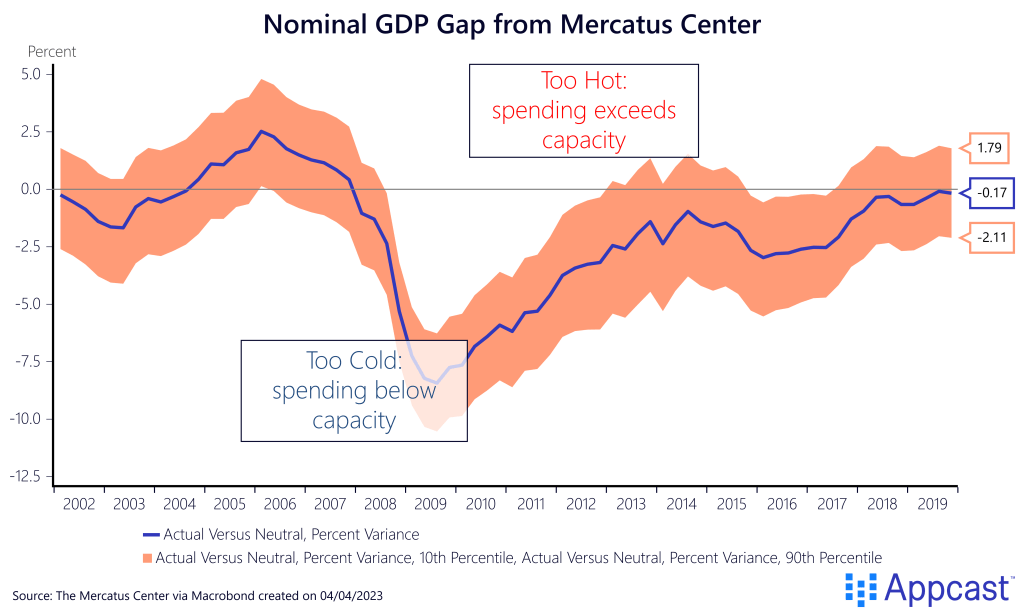

It is now conventional wisdom that monetary policy was too tight for several years following the financial crisis. Nominal GDP growth was extremely sluggish, and inflation was far below target. Nevertheless, the Fed decided to step on the brakes several times during the mediocre recovery.

The Mercatus nominal GDP gap, which measures to what extent total spending in the economy is falling short of expectations, shows that there was a negative gap for almost an entire decade from 2008 to about 2018.

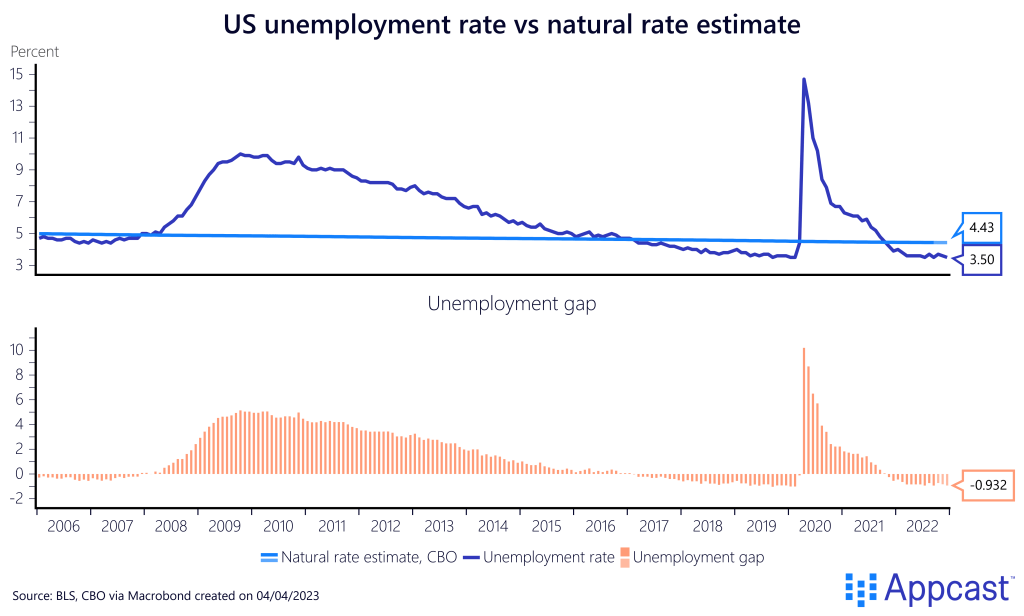

Nominal GDP growth was too sluggish for many years, which had a severe negative impact on the labor market. The following chart shows the gap between the actual unemployment rate and the newest estimate for the natural rate of unemployment.

The unemployment rate was above its natural rate for from 2008 all the way to 2017. More expansionary policies – including fiscal policy as well as monetary – could have led to a much quicker economic recovery with faster job growth.

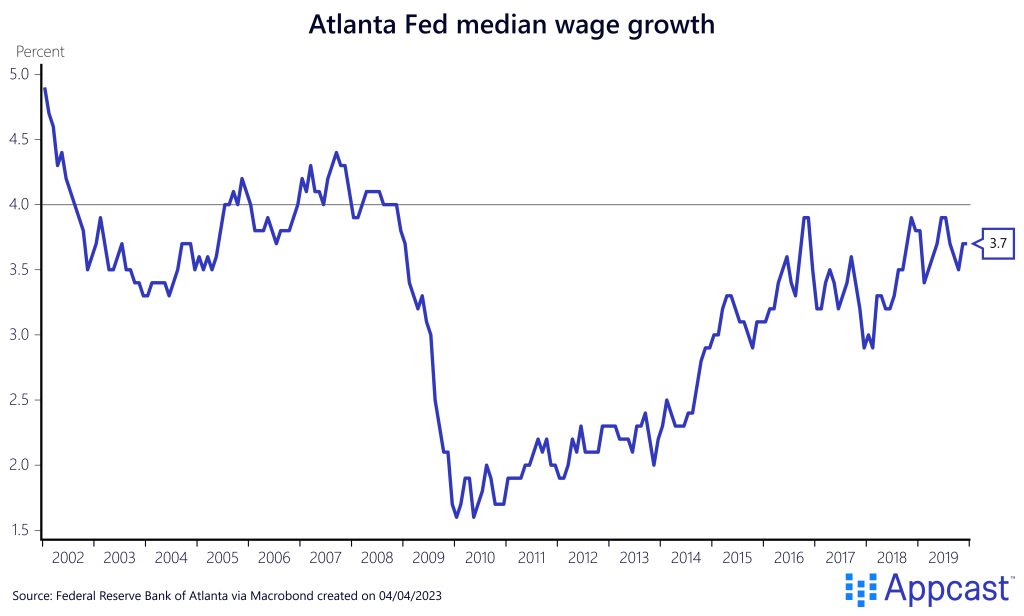

The weak labor market combined with subpar nominal GDP growth also led to weak wage gains for workers. In tandem with the unemployment rate, it took about a decade for wages to recover to pre-crisis levels.

The post-COVID economy shows that a faster recovery would have been possible. Policy makers thus sacrificed millions of jobs post-2008 simply because they thought that the economy was already operating close to full capacity and that there weren’t many idle workers left, a belief that turned out to be wrong!

Conclusion

Arguments about where the natural rate of unemployment are not just semantic but have real-life implications for millions of people. Monetary policy is steering nominal spending in the economy. Alan Greenspan deserves some applause for pushing back against some economists in the 1990s who also believed that the U.S. was at full employment. But they were wrong and the tech boom at the time pushed the unemployment rate to a new low, a hypothesis that Greenspan was willing to test at the time. The biggest mistake of the Bernanke and Yellen Feds were to not try and do the same after the financial crisis – a mistake that perhaps left millions of workers on the side-line. While Bernanke and Yellen’s Feds dealt with sluggish employment growth – potentially of their own creation – Powell’s Fed is dealing with a roaringly hot market. While this means the Fed chair avoided the mistakes of his predecessors, his inflation-fighting decisions will also have real-life implications on Americans.