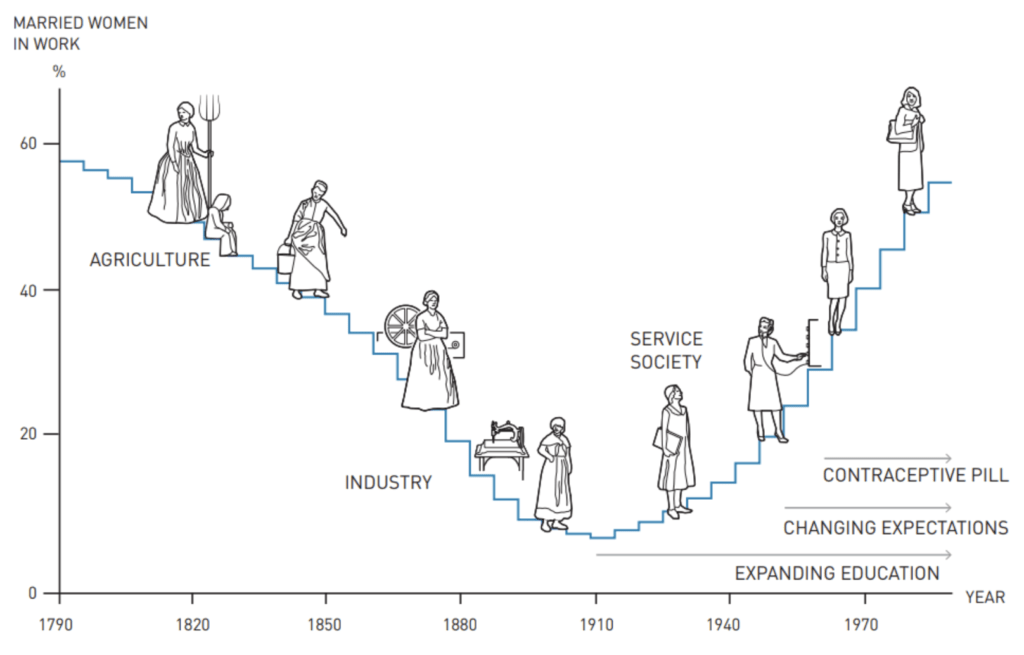

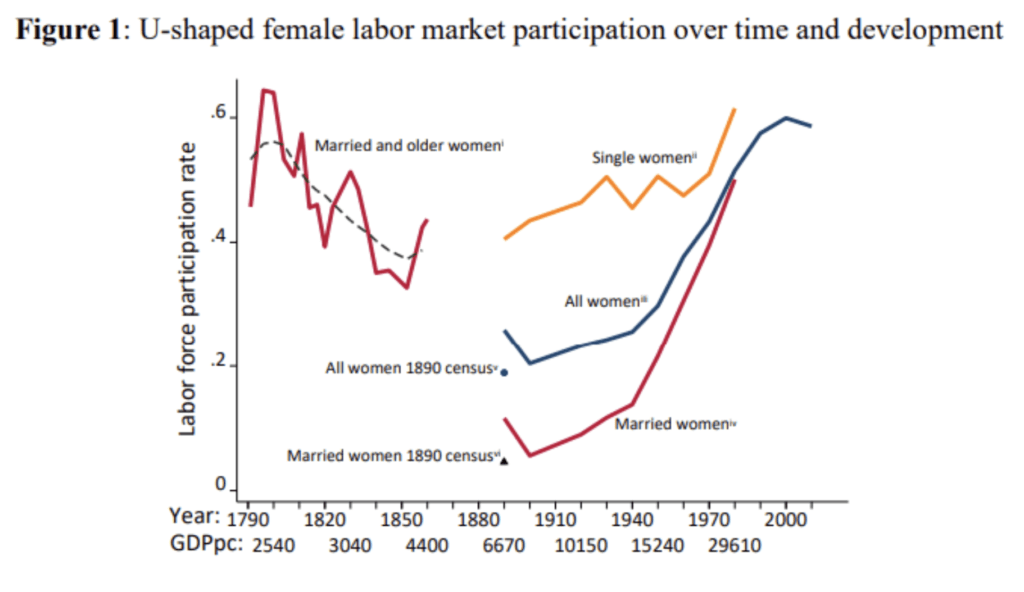

The U-shaped curve: Female labor force participation was higher before industrialization

Claudia Goldin is a U.S. economic historian and labor economist at Harvard University. Her research covers the impact of education and technology on labor market outcomes and inequality. She was awarded the Nobel Prize this year for her work on women’s labor market outcomes over time.

Her studies uncovered that female labor force participation of married women followed a U-shaped curve over the last 200 years in advanced economies like the U.S. She was one of the first researchers to push back against the widespread view that female employment rates are positively related with economic development.

Her historical research shows that it was very common for women in the in the pre-industrial society to work along their husbands in agriculture or various forms of family business. Women also worked in cottage industries or production in the home, such as with textiles or dairy goods. Women were thus more likely to participate in the labor force. However, that started to change with industrialization because it became more difficult for married women to work from home and to combine work with family.

Does that sound familiar?

Industrialization at the turn of the 20th century thus led to a significant decline in female employment for married women.

Expectations shape outcomes

Because female employment rates were significantly lower more than a hundred years ago, it wasn’t rational for women to invest in higher education. Moreover, social stigma and even legislation actively prevented married women from obtaining employment during the 1930s and the following decades. Therefore, women typically had very short working careers due to marriage and family.

Despite the changes to come in the postwar period, women continued to severely underinvest in education at the time because their expectations were formed based on the prior generation. Women in the 1950s and 1960s spent a significant amount of time in the labor force, but they would likely have invested even more in their careers had they expected this outcome.

Educational choices

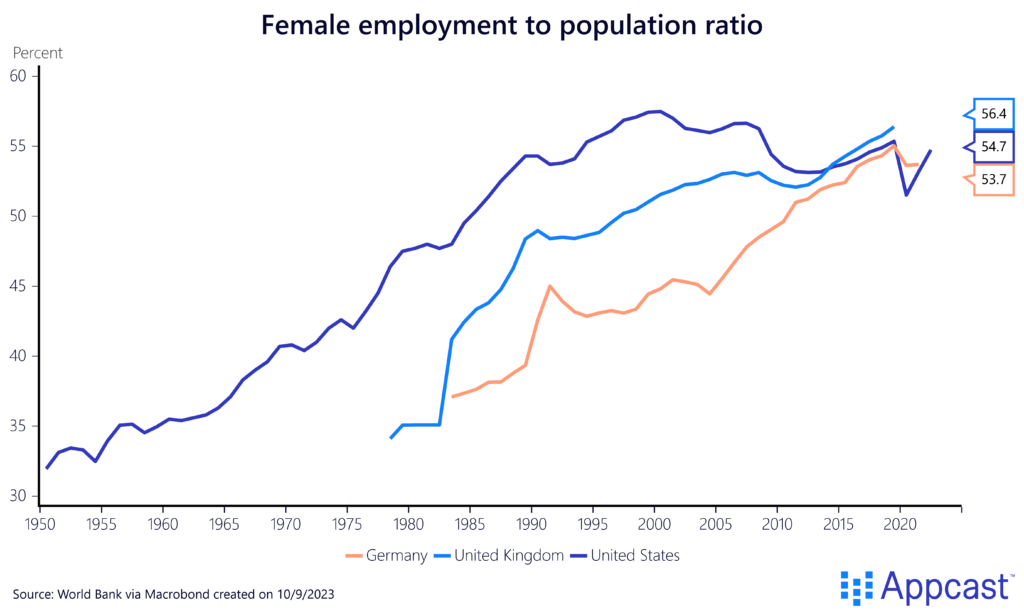

More opportunities started to arise for women in the postwar period, which brought along a continuous increase in the female employment rate across advanced economies over time.

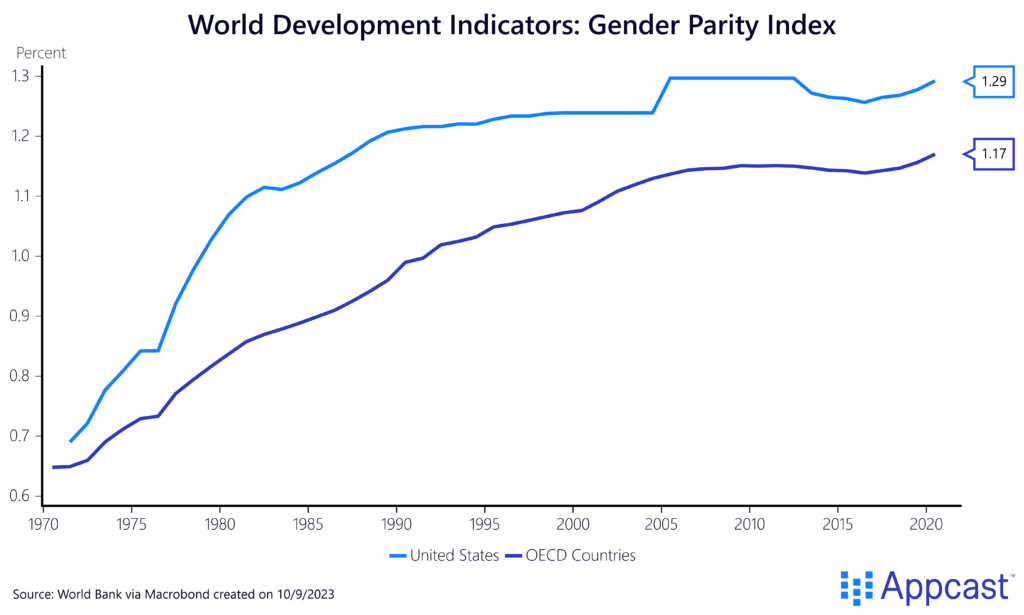

Together with better opportunities, women started to invest more heavily in higher education. The chart below shows the Gender Parity Index. A number below one indicates that more males than females are enrolled in higher education.

As one can see, since the 1980s in the U.S. and since the late 1990s across OECD countries, more women than men are enrolled in higher education. The education gender gap thus reversed already a couple of decades ago and is now significantly tilted towards women.

Research from the St. Louis Fed shows that the returns to getting an associate or bachelor’s degree are larger for women than for men. Achieving more education is thus an important way for women to make up for the gender pay gap.

The power of the pill

Even more important than access to higher education was the power of the birth control pill. Claudia Goldin’s research shows that access to contraceptive methods led to a significant boost in female employment after 1960, when the pill was introduced. It helped women delay marriage and childbirth, which in turn allowed for better career planning.

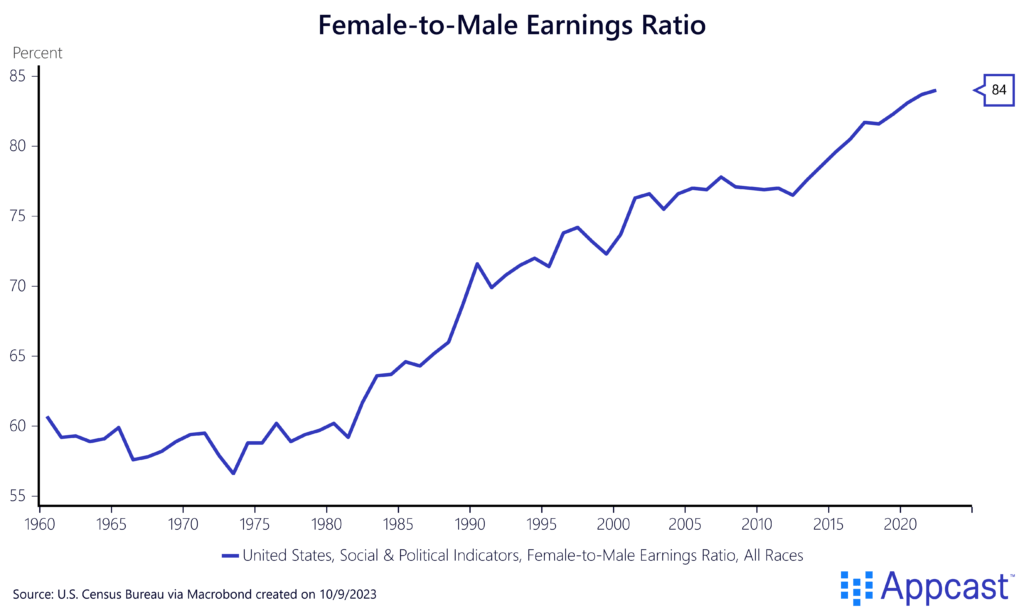

The female-to-male earnings ratio increased from about 60% in the postwar period to more than 80% in recent years.

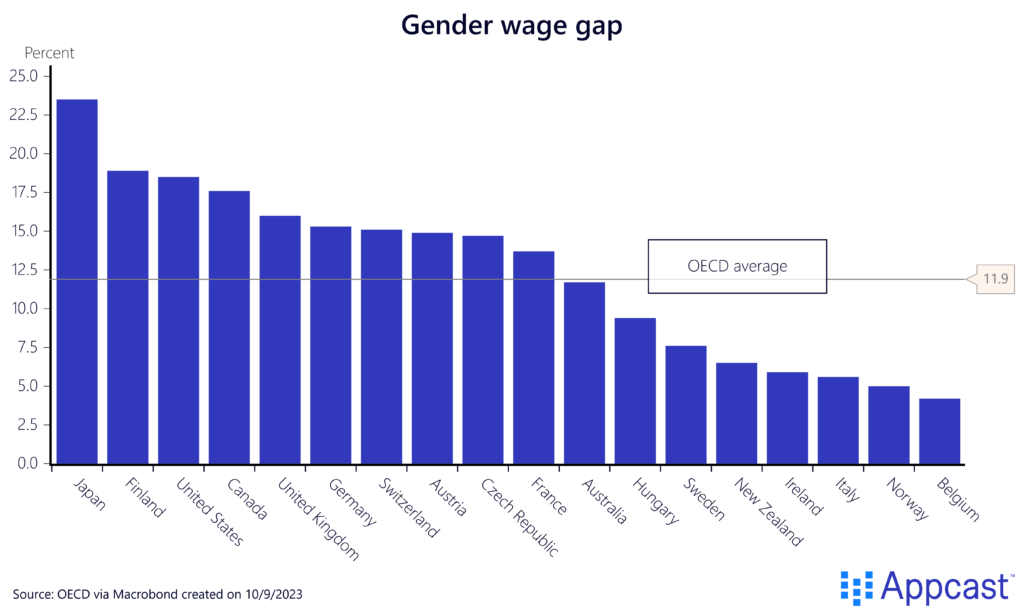

However, even though women are now better educated than men and can plan better when to start a family thanks to modern contraceptives, men are still better paid on average. While the female to male earnings ratio has improved in recent decades, the gender pay gap is still close to 12% across OECD countries.

Today’s labor market rewards flexibility and continuous employment

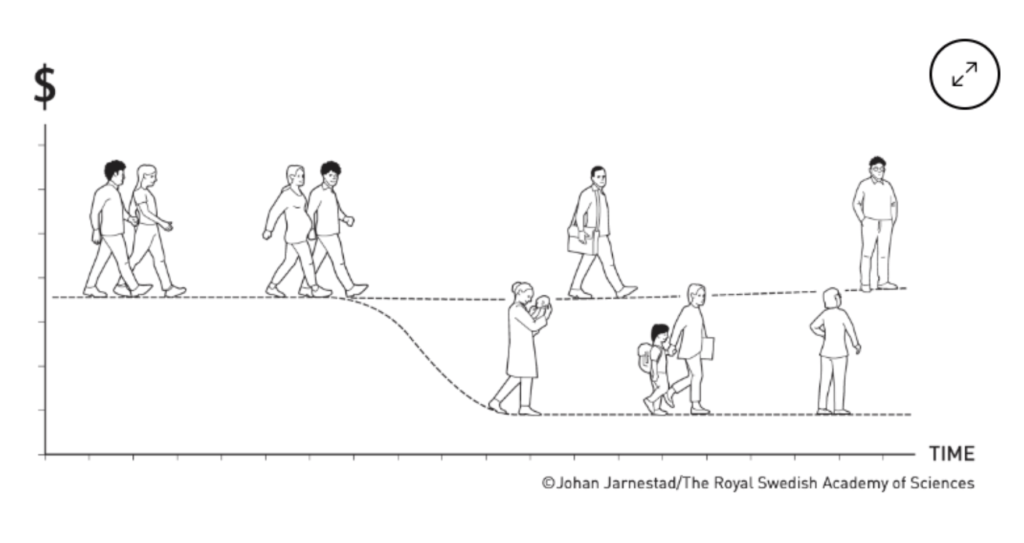

The reason for why the gender wage gap persists is that today’s labor market rewards long hours and flexibility.

It is not education or skills that explains the disparity in pay but childbearing: Time away from the labor market, and returning to the labor market at reduced hours, has long-term consequences on the female wage-earnings profile. There is also a wage penalty associated with flexible jobs that allow women to be the “on-call” parent.

Working from home: Equalizer or amplifier of inequalities?

The COVID pandemic obviously led to one of the largest changes the labor market has seen in decades. While working from home surged during the pandemic, a certain reversal is now underway. Many companies now promote hybrid work and are asking workers to come to the office at least a few times each week.

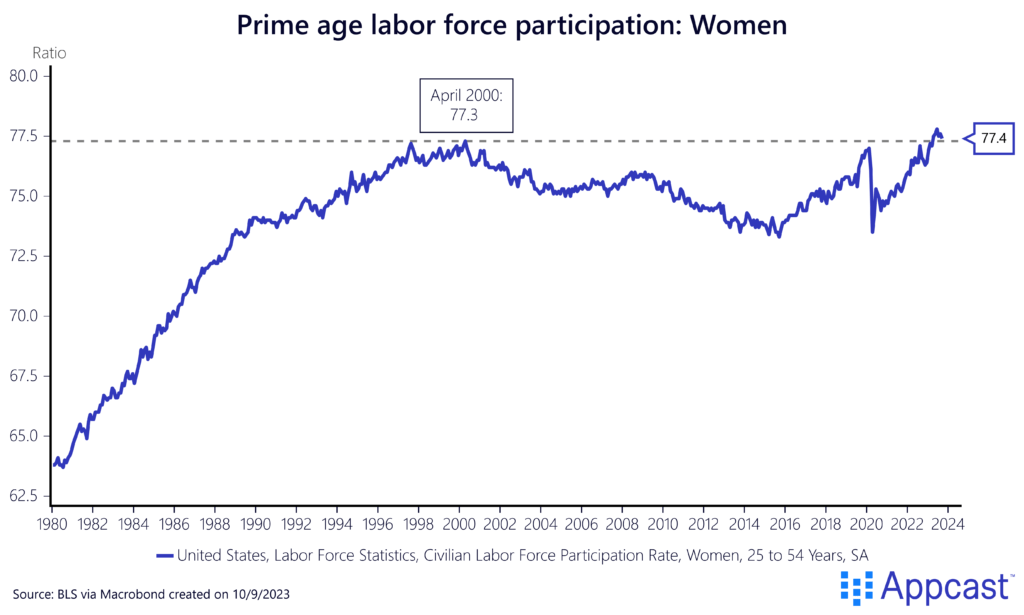

The flexibility that remote work offers has enabled more women to enter the labor market. Female prime age labor force participation now exceeds the previous highest level achieved back in the spring of 2000.

On the other hand, research shows that being in the office more often and having more face time with your managers and supervisors means that you will be more likely to get a promotion. And that means that women might miss out again if they are more likely to work from home because of child caring responsibilities.

While working from home can thus open opportunities that previously did not exist, it is maybe too early to tell whether it will be an equalizer or amplifier of inequalities for women’s labor market outcomes.