It’s difficult enough to guesstimate the potential impact Trump’s policies will have on immigration, which is what we attempted to do in our previous piece.

Modeling the impact on the economy and the labor market is even harder. Nevertheless, we have tried our best. Using a simple economic growth model, we estimate the impact on GDP and wages. In a subsequent step, we outline the inflationary response and how the Fed might potentially react to it. This piece will summarize the results of this modeling exercise.

The decline in the non-college-educated workforce and what that means for wage growth

Data shows that approximately 75% to 80% of migrants are of working-age, and the number is even higher for illegal arrivals.

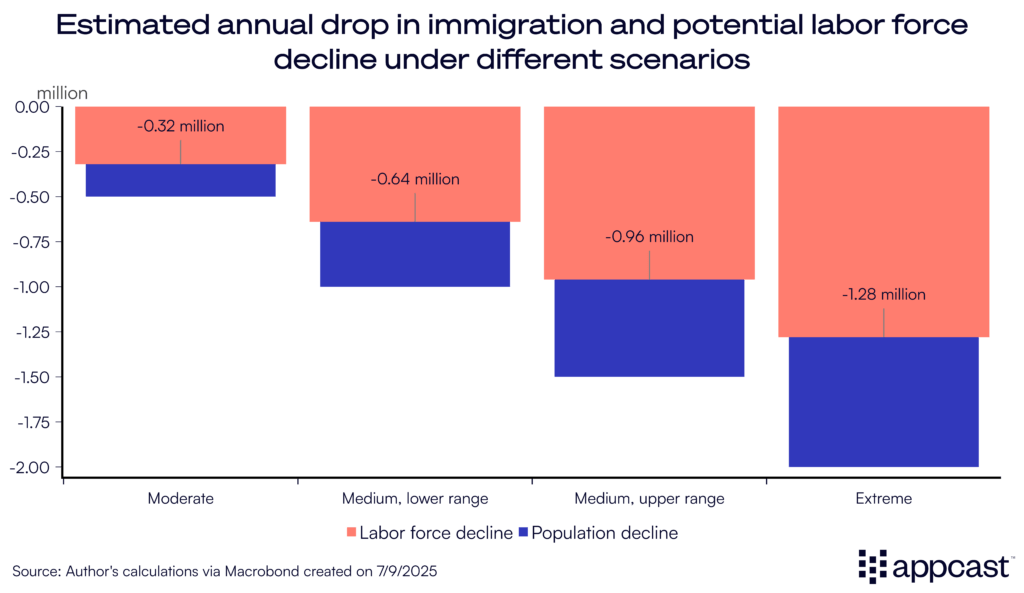

The labor force participation rate for those workers is typically high, close to 80%. Those two numbers help us translate the decline in immigration into a decline in the potential labor force. Between the moderate and extreme scenario, we are talking about annual drop in the potential labor force ranging from a little over 300,000 to just under 1.3 million. However, the range between the two medium scenarios seems the most likely outcome to us for now, given the capacity constraints that mass deportations are facing.

Since most of the decline is occurring via the plunge in illegal immigration—after all, a key objective of the current administration—let’s assign for simplicity the entire share of the drop to the non-college-educated workforce, which we assume to be about 80 million workers (roughly half of total employment).

Economic research suggests a wage elasticity between -0.15 to -0.75 for non-college-educated workers. We will assume a value of -0.4, meaning that a 1% decline in the low-skilled workforce increases wage growth by 0.4%.

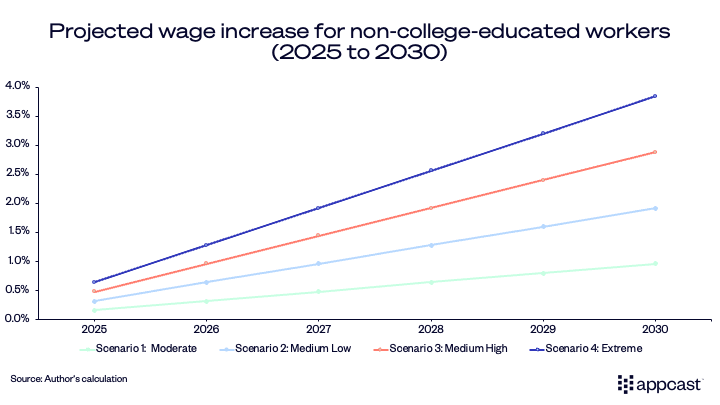

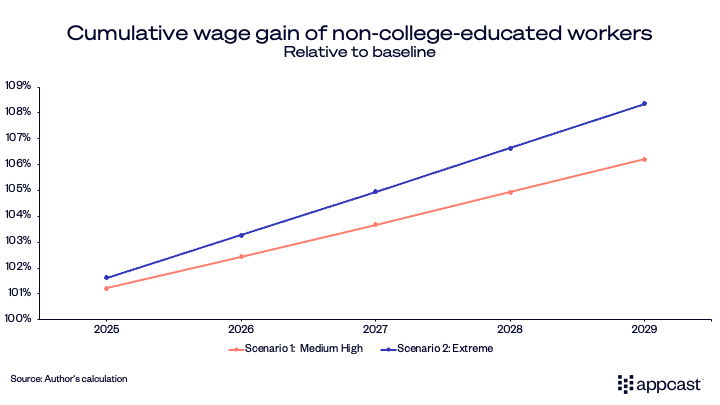

The graph below models the cumulative wage increase between 2025 and 2030 for the four distinct immigration scenarios outlined above:

- An annual decrease of 320,000 (moderate),

- 640,000 (medium low),

- 960,000 (medium high),

- and 1.28 million (extreme) in the non-college-educated workforce.

In the most adverse outcome, wages for this population increase cumulatively by an additional 4% between 2025 and 2030. We will see below that this is a quite conservative projection. Under different assumptions, wages are likely to increase at an even higher rate.

Assumptions: Wage elasticity of -0.4, total pool of 80 million non-college-educated workers, approximately half of U.S. employment. Annual declines equal approximately 0.4%, 0.8%, 1.2%, and 1.6% of the non-college educated workforce.

The effect on growth and wages of college-and non-college-educated workers

To answer the question how the decline in non-college-educated workers affects the economy, we use a very simple growth model with three inputs: Capital, non-college-educated labor, and college-educated labor. For simplicity, we’ll keep technology constant for now.

A key question is whether these two types of labor are substitutes or complements in the economy. Depending on the specific assumptions, a decline in the non-college-educated labor pool can have quite different effects on economic growth and how wages grow for the college- vs. non-college-educated workforce.

Unfortunately, economic research gives us no clear-cut answer on the question of substitutes or complements. Estimates about this one crucial parameter are all over the place, varying by country and time period (and potentially estimation technique). For our purpose, we will assume that substitutability between the two buckets of labor is relatively low. And we will make a similar assumption for the substitutability between labor and capital.

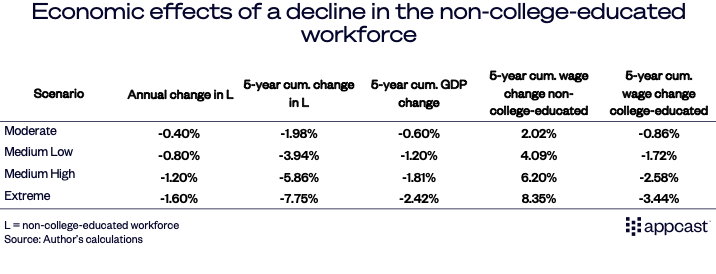

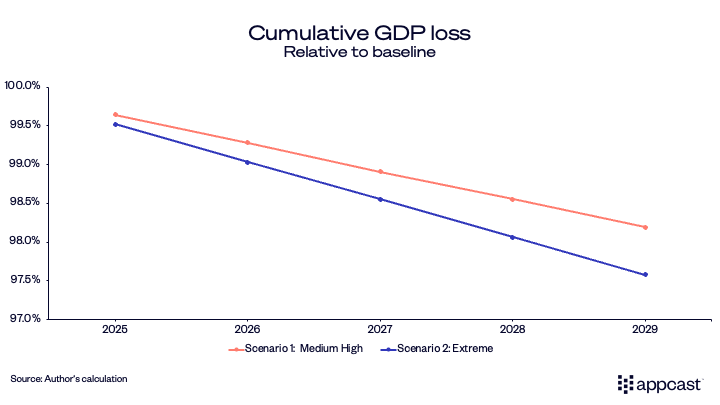

As we can see from our growth accounting exercise, the two extreme scenarios create a cumulative decline in GDP worth several percentage points over a five-year period, representing a significant drag on the economy. One should note though that this is relative to trend growth. On their own, restrictive immigration policies could therefore reduce trend growth for the U.S. economy from 2% to about 1.5% in the medium run.

Low-skilled wages increase by an additional 6% to 8.3% (note that the effect is roughly twice as large as the very simple calculation based on the wage elasticity above).

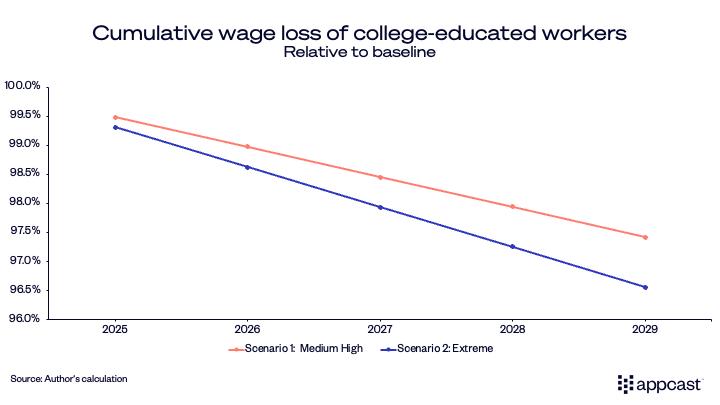

By the end of the period, wages of college-educated workers are between 2.6% and 3.4% lower relative to baseline as the economy becomes less productive (college-educated and non-college-educated workers are complements in this scenario).

Scenario “Medium High” and “Extreme” represent an annual loss of 1.2% and 1.6% of the non-college educated workforce.

While the effects above are certainly plausible, far different outcomes are within the range of possibilities. Three factors in particular can mitigate the adverse outcome from a large drop in the non-college-educated workforce: Technology, capital, and higher substitutability between the two types of workers.

Technology and capital deepening can mitigate worker shortages

Employing more capital instead of workers (automation) and/or deploying new technologies can compensate for the decline in the workforce caused by immigration restrictions.

One research paper has examined how the end of the “Bracero Program” (meaning manual labor) affected the U.S. labor market in the 1960s. Initiated during World War II to solve labor shortages, Mexican workers were allowed to work as seasonal hires in the agriculture and railroad industries until 1964. Between 1948 to 1964, the U.S. allowed in on average some 200,000 of these braceros per year. They represented a massive share of the agricultural workforce in Southern states, until the program was ended abruptly under President Kennedy.

Contrary to expectations and defying the aim of the policy, the end of Bracero workers did not boost the size of the domestic workforce in agriculture in the states that were affected the most. Furthermore, it also had no significant effect on workers’ wages.

How come? Productivity growth in agriculture back then was extremely high. Farmers started to use different technologies that could automate more of the work. They also switched to less labor-intensive crops. Even though a few hundred thousand workers were suddenly missing, the end of the Bracero Program did not have any substantial labor market effects because technology compensated for the loss of the workforce.

The big question obviously is whether this is equally applicable today. The Bracero Program only affected one specific sector – agriculture – and a specific type of worker – seasonal hires – whereas a substantial reduction in the foreign workforce today would hit many different sectors of the economy. While some industries might be able to compensate with higher automation, automation potential varies significantly by sector and occupation. Elder care, accommodation, hospitality, and even construction might struggle to automate past a significant decline in workforce.

What if college-educated and non-college-educated labor are not complementary after all?

If non-college-educated and college-educated workers have a higher substitutability, firms can more easily replace one type of labor with another. While the economy-wide fall in GDP remains relatively similar, the behavior of wages is different. Wages for non-college educated workers would rise by several percentage points less than in the case above. Meanwhile, college-educated wages would not decline as much. This would represent a more benign inflation outcome.

What does this mean for inflation, and how will the Fed respond?

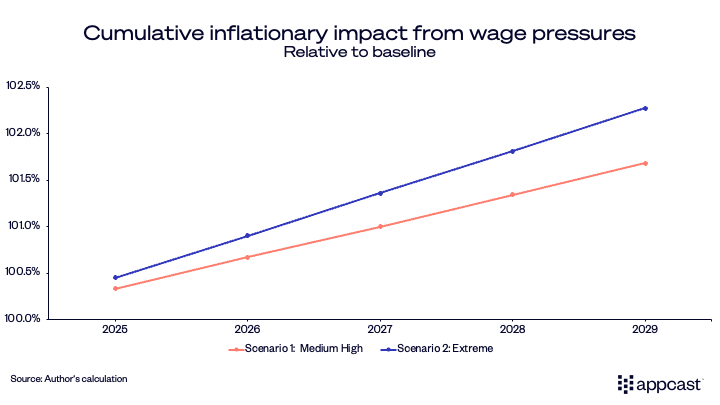

The results from the simple growth model above do not incorporate the effects of inflation, or how the Fed might react to such a negative labor market shock. While the increase in non-college-educated wages is certainly inflationary, wages of college-educated workers move in the opposite direction because of the assumed complementarity. The reduction in the non-college-educated workforce makes the economy less productive, depressing output and wages of the college-educated workforce, thus muting the inflationary impact of the worker shortage to some extent. This is extremely important because it means that the Fed’s monetary response will also be more benign and therefore create less harm for the economy.

How big the inflationary impact will turn out to be depends on how labor-intensive production is in each area of the labor force. Typically, it makes sense to assume that the non-college-educated sector has a labor share of around 75% while the college-educated sector has a labor share of 50%.

Using those numbers as a benchmark and assuming that the CPI is equally exposed to the college-educated and non-college-educated sector, we get a cumulative increase in the CPI of more than 2.3% (1.7%) over five years if the labor pool of non-college educated workers shrinks by 1.6% (1.2%) annually.

Inflation thus increases by about 0.3 to 0.45 percentage points each year as the workforce declines. This, in turn, leads to more restrictive monetary policy from the Fed, meaning a higher path of future interest rates.

Using a standard new-Keynesian macro model, we can estimate what the effect on the economy would be a 0.3 percentage point annual increase in inflation, leading to a 0.75 percentage point increase in the Fed policy rate in the first year with up to two more rate hikes in subsequent years. And higher interest rates have to be maintained throughout the period to contain the inflationary pressures.

Such a monetary policy reaction creates an additional GDP drag of about 0.3 to 0.4 percentage points in the first year, with smaller negative effects in the following years. The cumulative GDP decline adds up to about 1.3 percentage points, implying an increase in the unemployment rate of about 0.65 percentage points. This equates to a million jobs lost over a period of several years, offsetting some of the higher wage growth coming from restrictive immigration policies. While this sounds substantial and certainly represents an additional drag on job creation relative to trend, it wouldn’t be enough to create a recession. Remember that the U.S. labor market creates some 1.5 to 2 million jobs each year.

Note though that the numbers above are conservative estimates about how monetary policy would restrict output and employment, based on two critical assumptions: First, inflation expectations need to be well-anchored. Second, the Fed needs to allow inflation to overshoot target temporarily before bringing it back down. Output and employment losses are larger if one or both assumptions are violated. However, the evidence from the inflation overshoot following the pandemic speaks in favor of both.

The Fed’s monetary response to the additional inflation therefore creates an additional negative shock for the economy. However, it is unlikely to be large enough to create a recession, and its effect on GDP growth is also an order of magnitude smaller than the restrictive immigration policies themselves.

Nevertheless, whether half a million jobs are lost or not can make a massive difference for thousands of households in the country.

We did not model the negative effects higher interest rates might have on America’s debt burden. Given the public’s dire fiscal position, higher rates add to the increasing interest rate expenses that the U.S. government needs to pay on its debt. And that means that there are additional negative growth effects associated with the higher interest rate policy the Fed needs to implement to contain wage growth.

Conclusion

A significant reduction in immigration, potentially reducing the U.S. non-college-educated workforce by up to a million workers per year, has substantial implications for economic growth and the labor market. U.S. GDP in 2030 would be several percentage points lower than anticipated, implying an average loss of several thousand dollars of income for every single household in the country. Such a large reduction in the non-college-educated workforce increases wages for those workers by up to 8% between 2025 and 2030, whereas wages of college-educated workers fall by a couple of percentage points.

However, there is large uncertainty over these numbers. A higher substitutability between the two types of workers would lead to lower wage growth for the non-college-educated workforce. Similarly, wage pressures would be much more benign if technology and capital-deepening can absorb some of the negative labor market shock. And households cannot observe the hypothetical counterfactual world in which immigration is not reduced and might therefore not directly feel the decline in lost purchasing power they are suffering as a result.

The inflationary effects of Trump’s restrictive immigration policies also imply a higher interest rate policy from the Federal Reserve, which leads to a further reduction in GDP and additional job losses of up to one million, which could offset some of the wage gains.

While the restrictive immigration policies could lower U.S. trend growth by up to 0.5 percentage points, this is not enough on its own to create a recession or significant labor market downturn. That likely remains true when accounting for the Fed’s contractionary response to somewhat higher inflation.

That Trump’s immigration policies are not recessionary on their own does not negate the fact that they are imposing a tremendous amount of harm of hundreds of thousands of people. Families are torn apart by deportations, workers are driven into hiding by ICE raids, and migration statuses revoked or altered. All of these factors are set to undermine social cohesion within the country and will damage America’s reputation for years to come.