Correction (May 16, 2023): An earlier version of this story misstated the Republic of Ireland’s population as four million. Ireland has a population of five million. We apologize.

The well-known Irish GDP distortion

Ireland has seen some stunning economic growth in recent decades. Once one of the poorest economies in Western Europe, it has been among the star performers since the late 1990s. Dublin now harbors a lot of jobs in the finance and tech sectors, and local wages and prices in the capital are now approaching or even exceeding London levels.

But it should also be no surprise to anyone that a substantial part of Ireland’s economic activity is a result of its corporate tax regime. In fact, Ireland’s gross domestic product (GDP) is massively overstated as international companies have used the country’s low corporate tax rate to shift economic activity to Ireland. This includes pure profits – Apple’s Irish profits amounted to close to 70 billion USD in 2022 – and intangible assets like patents, which can be easily moved across countries.

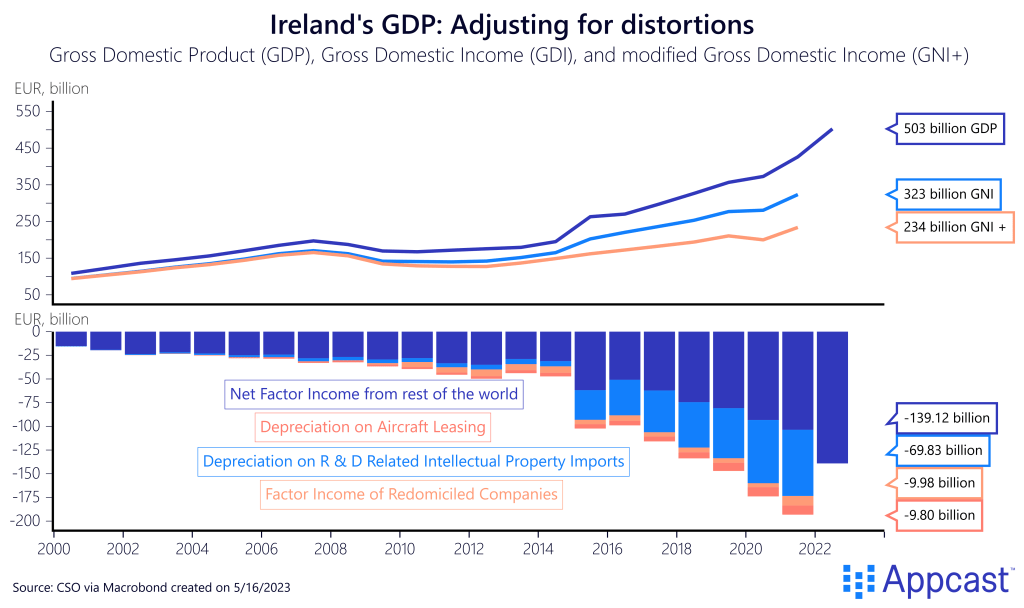

Paul Krugman famously dubbed this phenomenon “Leprechaun economics” after Ireland’s GDP grew by more than 22% in 2015 due these tax shenanigans. Irish GDP was just a little over 500 billion euros in 2022. Gross national income (GNI) is substantially lower though, by about 140 billion. By repatriating the profits from Irish subsidiaries to their parent companies, GNI is a relatively more accurate measure of Ireland’s economy. But even GNI is not fully accurate.

Philip Lane, European Central Bank chief economist and former chief economist of the Irish Central Bank, a world-renowned expert on international capital flows, has written several research notes on the dynamics of Leprechaun economics. He also chaired a committee that created a modified measure for the Irish economy called “domestic demand,” which aims at removing GDP distortions.

The depreciation of intellectual property (patents residing in Ireland), the depreciation of aircraft leasing, and the factor income of redomiciled companies (companies being headquartered in Ireland for tax purposes but having little economic activity in the country) also needs to be accounted for. This subtracts another 90 billion euros in 2021 from Irish GDP: 70 billion for the depreciation of intellectual property and 10 billion each for both aircraft leasing and the factor income of redomiciled companies.

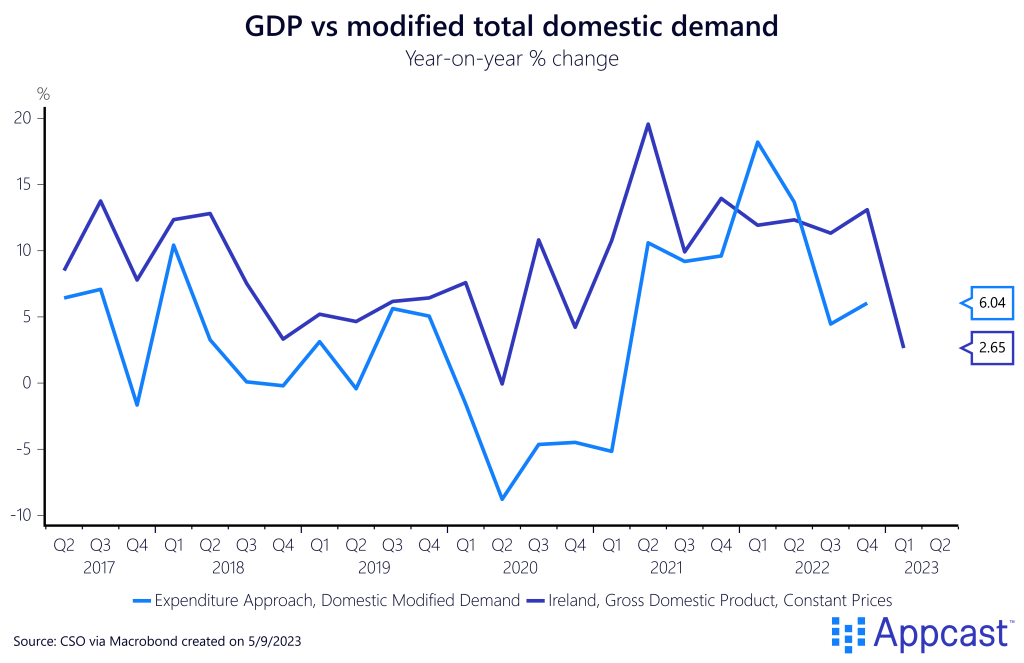

The following chart gives you an idea of the disparity between the two series. While Irish GDP increased by close to 20% in the beginning of 2021 and more than 13% at the end of 2022, modified domestic demand was only increasing at a rate of 6% at the end of last year.

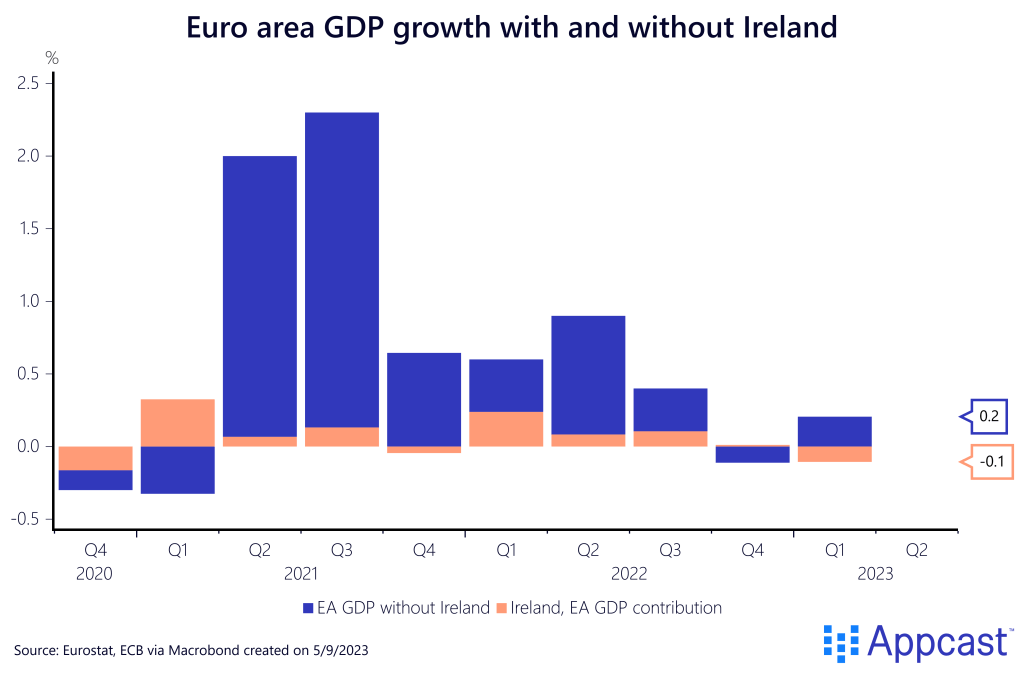

The size of the Irish distortion is so large that it even affects eurozone GDP and trade statistics. You know that there is something off when a country with five million inhabitants can distort the GDP of an economic area with more than 340 million people.

Ireland’s GDP contributed to almost half of eurozone growth in both Q1 of 2021 and Q1 2022, and Ireland was the only reason why eurozone GDP didn’t contract in Q4 of 2022. In Q1 2023, on the other hand, Ireland contributed -0.1 percentage points to eurozone GDP growth of 0.2%. In other words, eurozone growth would have been 50% higher if it wasn’t for Ireland’s negative contribution.

Distortions aside, Ireland has become much richer

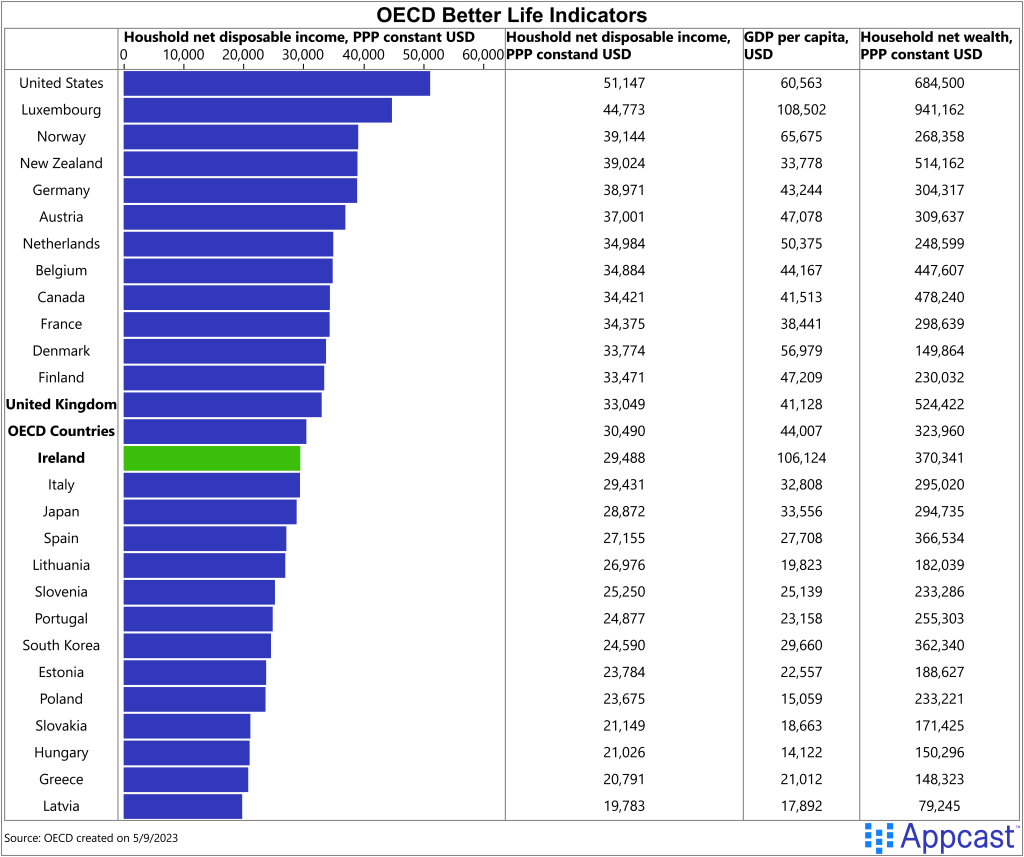

There is no doubt that the spectacular growth that Ireland has experienced in recent decades has also lifted living standards quite significantly. For Ireland, though, per capita GDP is not indicative of this shift at all because of the size of the distortions mentioned above. Per capita GDP is currently at about $100,000 USD, close to that of Luxembourg, a small country with about 600,000 inhabitants that is also a global financial center.

A much better measure of well-being is household net-adjustable income, which is the money that the average household has at their disposal after taxes and transfers, adjusted for Purchasing Power Parity (PPP). On that score, Ireland is barely average and still scores slightly lower than the U.K. and OECD average.

That being said, Ireland was relatively poor by Western European standards in the early 1990s and has made massive progress in terms of economic development since then.

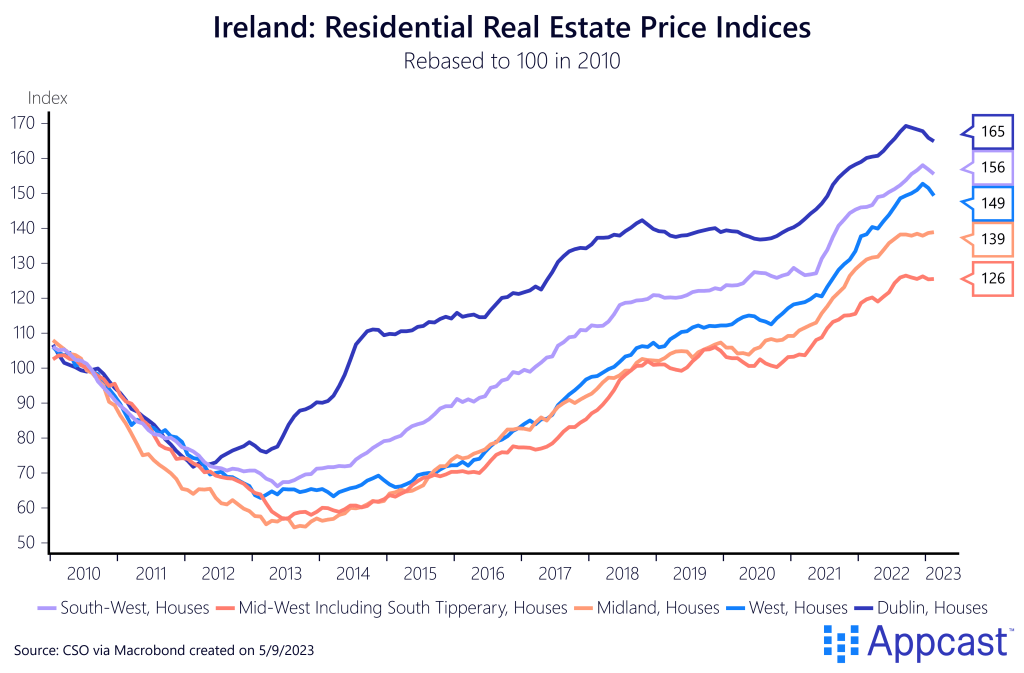

In terms of average household net wealth, Ireland scores higher than the average in OECD countries. Part of the reason is that, like other Western European economies, Ireland has experienced a massive real estate price boom in recent decades. Residential real estate prices basically doubled between 2012 and early 2023. The median house in the Dublin area is now close to 430,000 euros.

While this is benefitting real estate owners, it is also creating a massive cost-of-living crisis for renters and hurting the domestic economy as foreign workers struggle to find housing.

What’s up with the Irish labor market?

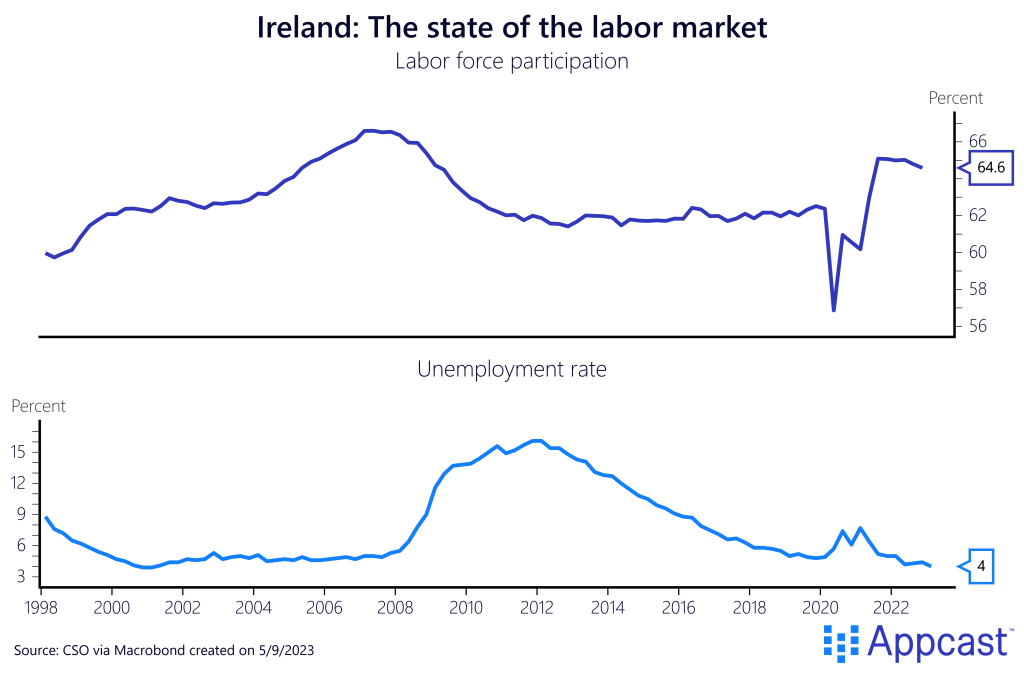

Despite the recent wobble in the tech sector with US companies announcing some major layoffs, both in the U.S. as well as abroad, Ireland’s labor market is currently at full employment. The unemployment rate hasn’t been as low as it is right now since the period before the financial crisis. Employment has increased since the beginning of the pandemic and the participation rate is now two percentage points higher than in 2019.

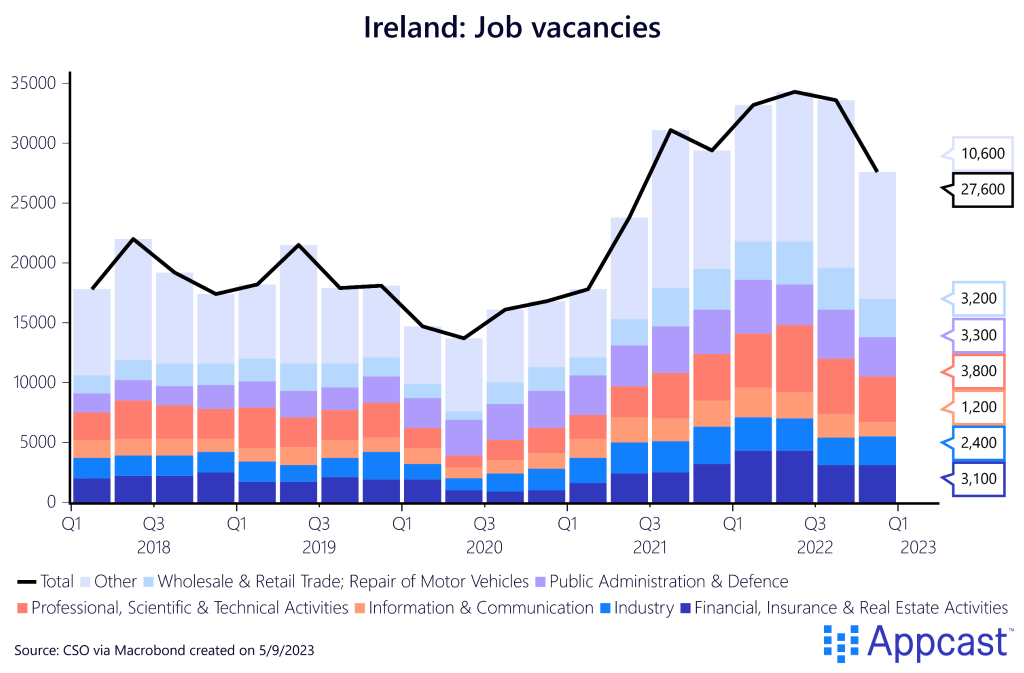

Job vacancies have recently slowed down quite a bit. However, compared to the pre-pandemic period, they are still elevated. There are some interesting sectoral divergences though. Vacancies are still quite elevated in wholesale and retail trade, in the financial, insurance, and real estate sector, as well as in construction. Information and communication, on the other hand, together with accommodation and food services, have recently seen a severe slowdown.

This is not entirely surprising. Ireland’s tech sector is currently being threatened by a wave of layoffs that originated in the United States. American tech companies that have large offices in Dublin have recently started to reduce their workforces there too.

Employment in the information and communication sector increased massively since the beginning of the pandemic – it’s up by more than 25% since the end of 2019 and most of the employment gains happened throughout 2021.

Large tech companies apparently overexpanded during the early stage of the pandemic and some of the excessive hiring is now being undone by layoffs.

While the Irish IT sector might see some further employment losses in the year to come as the global tech sector retreats, there is no reason to believe that all the job growth from the prior two years will be reversed. Notably, employment in IT only comprises about 4.6% of the total workforce. So far, the troubles in tech have not spilled over to other sectors.

Conclusion

Ireland has been one of the most stellar economic performers among advanced economies in recent decades. The country’s growth has now led policy makers to propose the creation of a sovereign wealth fund to channel its current budget surpluses into long-term investments.

However, about 50% of Ireland’s GDP is a direct result of its status as international tax haven that has prompted companies to shift profits and intangible assets to Ireland. The problem is well-known among policy makers, prompting the Irish Central Bank to construct an index called domestic demand that more accurately reflects the economic activity that is generated domestically.