The post-pandemic labor market has been extremely tight with many vacancies left unfilled. Many advanced economies are facing severe demographic headwinds. This means that the worker shortage will dominate the labor market of the future and employers will have to start preparing for this new reality.

The post-pandemic labor market: Hot and tight

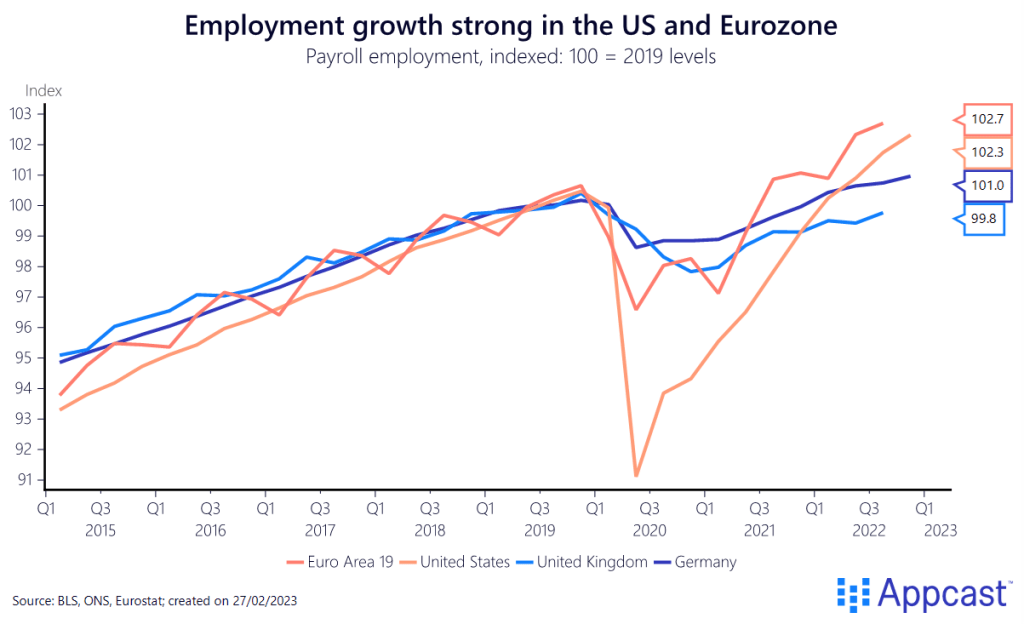

The rapid recovery from the Covid-19 economic shock has created tight labor markets in most advanced economies. Generally speaking, the recovery was much faster from the pandemic recession than many forecasters predicted, with employment now exceeding pre-crisis levels in most major economies.

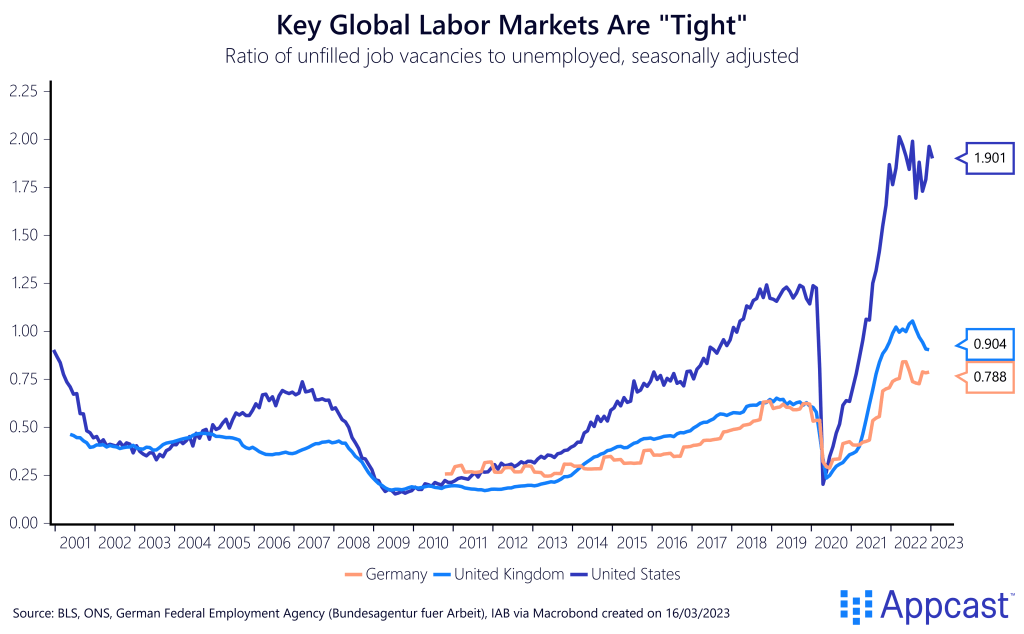

The ratio of vacancies to unemployed persons has surged to unprecedented levels as there have been more vacant positions than unemployed persons, especially in the U.S. but also in the U.K. last year. The U.S. has been seeing the hottest labor market in decades and recruiters have been struggling to fill positions in the post-pandemic economy.

Somewhat surprisingly, employment levels bounced back very quickly after 2020 and are now higher than they were before the Covid pandemic.

Participation rates have also recovered quite nicely and are close or even exceeding their pre-crisis level, which is obviously great news. It also means that the currently low unemployment rates are not just the result of workers leaving the labor force en masse, or stopping to look for jobs.

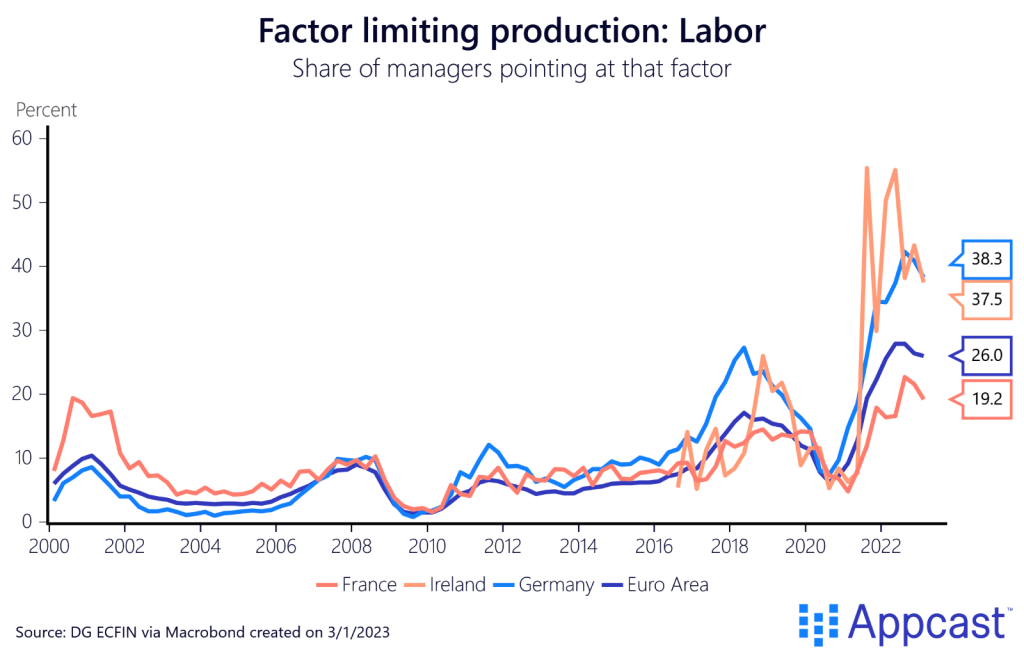

Despite the fact that employment levels have bounced back, more companies are citing labor as the limiting factor of production. In the Eurozone, Ireland and Germany seem to be particularly affected.

Long-run demographic trends: Is “Unemployeement” the future?

“Arbeiterlosigkeit” is another complex German word that you might want to add to your vocabulary. Coined by Stepstone CEO Sebastian Dettmers, it means “unemployeement” or shortage of workers, and Germany is one of the countries that will be the most affected in the long run. The demographic outlook across high-income countries is challenging, to say the least, and it would be even more grim if immigration was not adding to the workforce already.

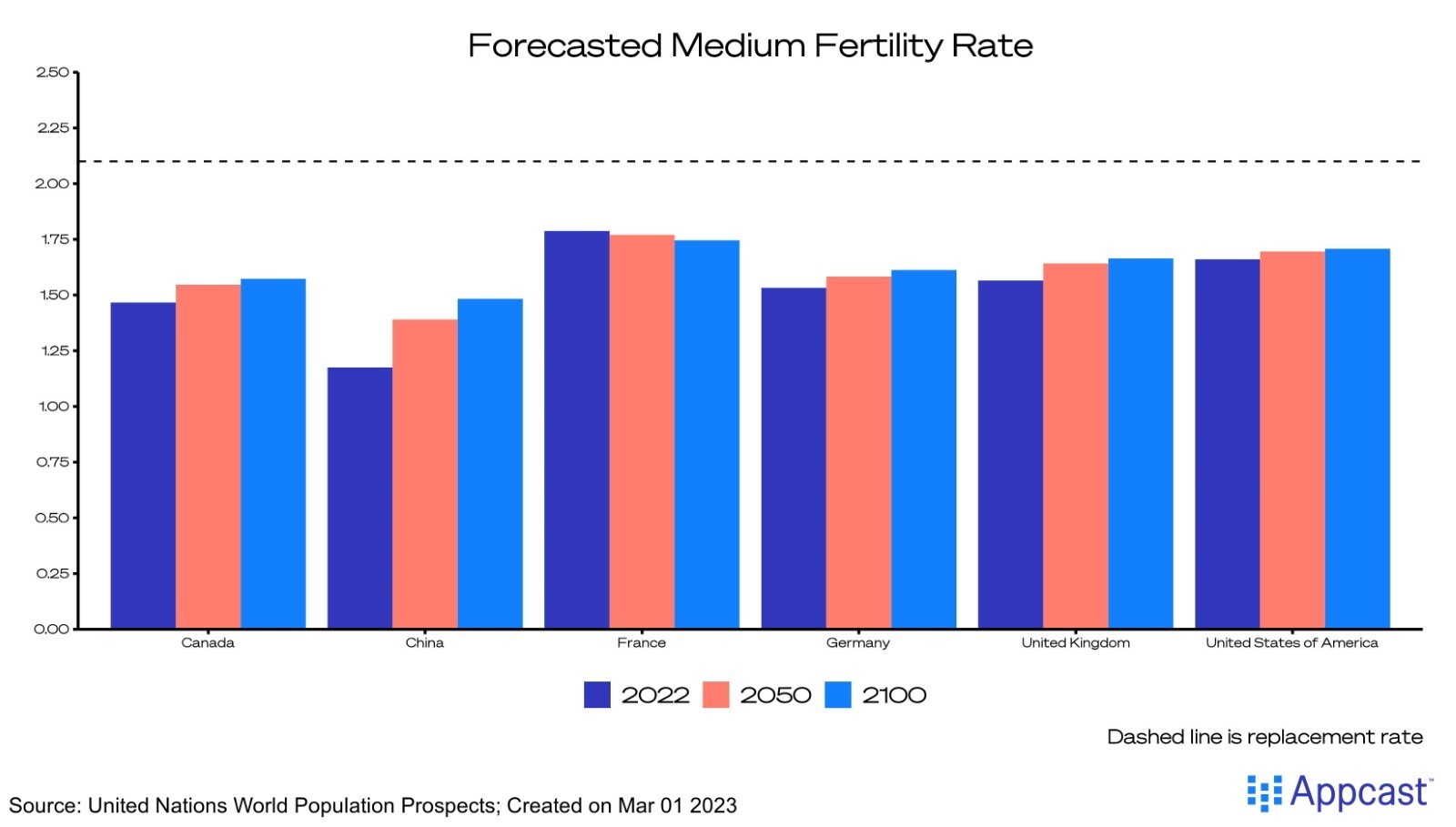

A fertility rate of slightly above two is required to keep the population stable. All advanced economies have been having fertility rates below that threshold since the 1980s and even earlier. Germany is well-known for having the most severe demographic problem next to Japan; meanwhile, countries like the U.K., France, and the U.S. are still recording somewhat higher birth rates.

Emerging market economies have also seen declining fertility rates in recent decades as they’ve become richer. China obviously stands out where the one-child-policy has been implemented for decades and led to record-low fertility numbers for a country that is still relatively poor.

Demographers forecast that fertility rates across advanced economies will remain below two for the foreseeable future, and the same is true for China.

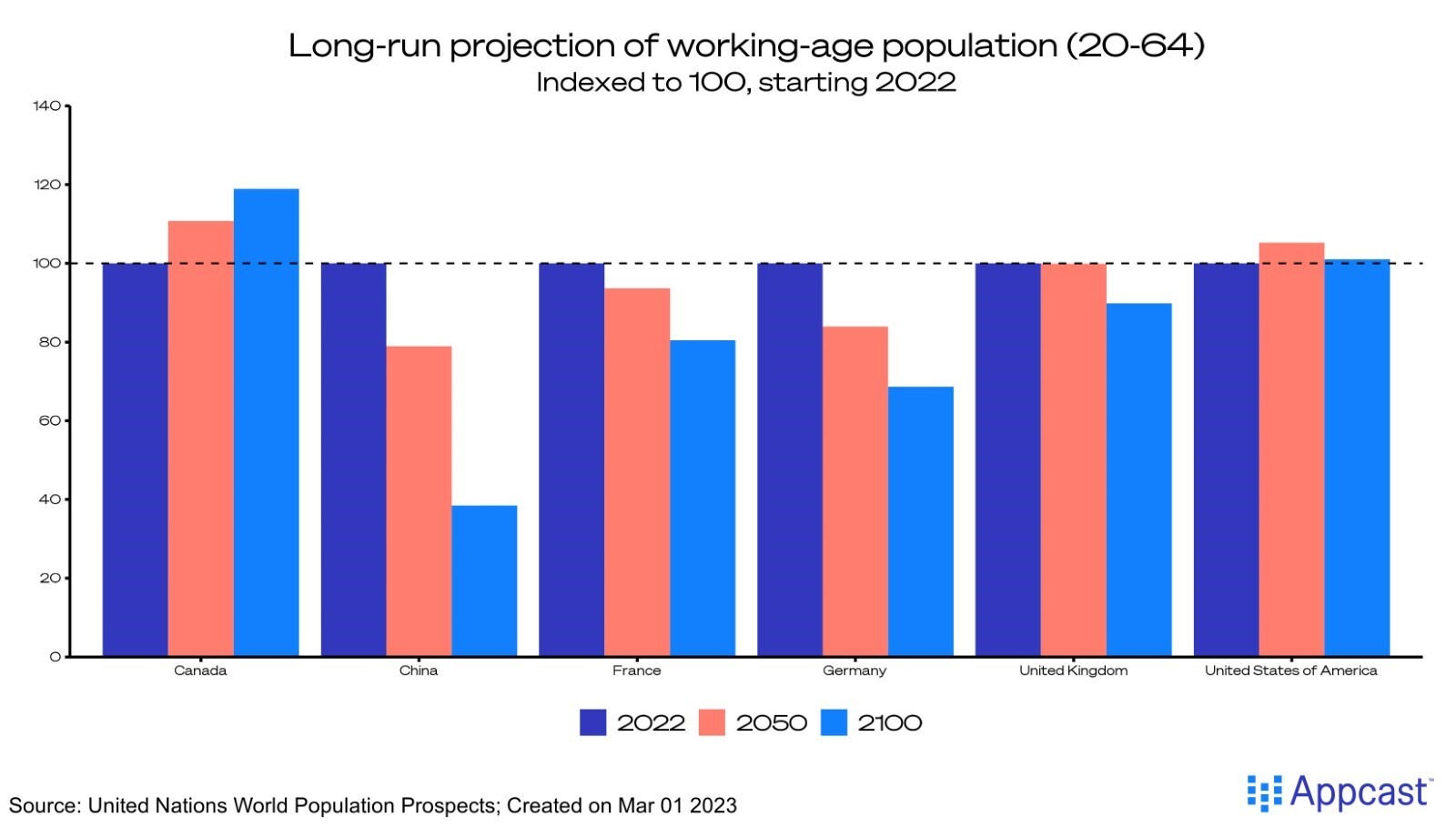

As such, long-run projections for the working-age population look rather grim for many countries. Absent large net-migration inflows, the working-age population will shrink by some 20% until 2050 in both Germany and China. France will only see a modest decline in the workforce and Britain’s labor pool will stay constant.

It is only the U.S. and Canada and other high-immigration countries that will see their labor pool expand in the coming decades.

What does it mean for recruiting?

The shrinking workforce will lead to enormous challenges in the countries that are affected. Recruiters in Germany have already been complaining about a shortage of skilled workers for years now and the solutions to the problem are unlikely to be a one-size-fits-all strategy.

More flexible working arrangements are key to recruit and retain workers. Work-life balance is high up on the list of job seekers’ priorities. Employers who are willing to go the extra mile will have more luck attracting skilled workers.

While this will apply more to white-collar jobs, offering hybrid work and having more flexible working hours can be an incentive and bring some workers back into the workforce who otherwise would be unable to – think of mothers with young kids, for instance.

New research shows that hybrid work can also boost productivity. About 40% of the savings of commuting times goes to work and another 40% goes to leisure in countries like the U.K. Hybrid work can thus benefit both employers and employees alike.

A recent pilot project in the U.K. implemented a four-day work week and the results were so beneficial for both the employees and the companies that participated that almost all of them are sticking to this new work schedule.

Upskilling and reskilling programs are also key. The speed of technological change in many work-related tasks means that employers need to play a big role in upskilling their workers, such as by subsidizing further university courses.

Automation and higher productivity gains are in the long run the one big driver that we need to rely on for higher living standards. Labor-saving technologies can boost economic growth and make up for the upcoming demographic decline if technologies evolve in that direction.

However, many employers are currently concerned that technology ultimately might not make up for the decline in the workforce that countries like Germany are facing. And rightly so – there is no guarantee that technology can be directed towards solving the shortage of workers.

Tapping into the global labor pool

The most obvious solution – though also politically the most challenging – to fix the worker shortage in advanced economies is to tap into the global labor pool.

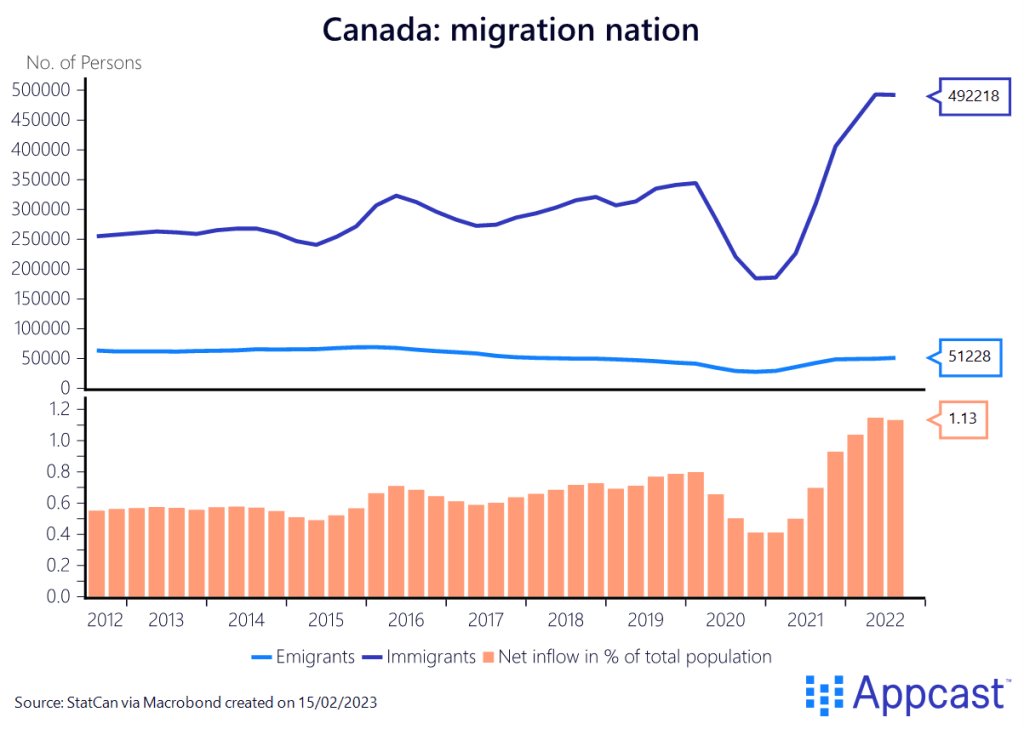

Canada is probably the role model when it comes to migration. The number of immigrants coming into the country has been historically high: the inflow exceeded 0.6% of the total population on an annual basis and this has now increased to more than 1% as of last year.

Their point-based immigration system ensures that the country receives a steady flow of skilled workers, while at the same time, Canada is also generous to asylum seekers.

Conclusion

The worker shortage will be one of the biggest challenges for companies and recruiters in countries like Germany. Additionally, it will also be massive burden on the pension system and will shape the geography of cities. Policymakers in Japan are already trying to concentrate the declining population in key urban areas to rein in spending on infrastructure.

While technology can solve some of these problems, tapping into the global labor pool like Canada does, will be a necessary step to tackle the demographic decline. Technology and immigration will have to be key components to address the upcoming worker shortage.