In our final segment of this four-part series on immigration, we will discuss the industries and occupations in the United States that are highly reliant on migrant labor. Those will be affected the most from the worker shortages that large-scale deportations and migration restrictions would inevitably entail.

The preceding pieces examined the national impact of Trump’s immigration policies (here and here) and how they might affect different regions within the U.S. Unsurprisingly, California, Florida and Texas will suffer more from a significant curb of immigration as some industries are very reliant on foreign labor: More than 30% of hospitality workers in Florida, some 30 to 45% of workers in construction and transportation and warehousing in Texas, and more than two thirds of California’s agricultural workers are foreign-born.

What industries have a high share of foreign-born workers?

Let’s start with the facts. About 20% of workers in the U.S. today are foreign-born, a record high.

Data from the Census Bureau shows that education and healthcare, professional business services, construction, manufacturing, retail, hospitality, and transportation have the largest immigrant workforce. Several million foreign-born workers are working in each of these sectors.

But obviously, some of these sectors are larger in terms of total employment numbers than others. The share of foreign-born workers is highest in construction, with almost 30%. Professional business services and other services like transportation, hospitality, manufacturing, and agriculture follow with a foreign-born workforce between 20 and 23%.

In other words, in the most vulnerable sectors, every fourth worker (and every third in construction) has a migration background.

This isn’t new, but the reliance on foreign-born workers has risen significantly in the last decade. Between 2013 to 2023, construction’s share of foreign-born workers has increased by six percentage points, professional and business services and transportation by about five percentage points, financial activities and public administration by about three percentage points.

Immigrant-heavy occupations

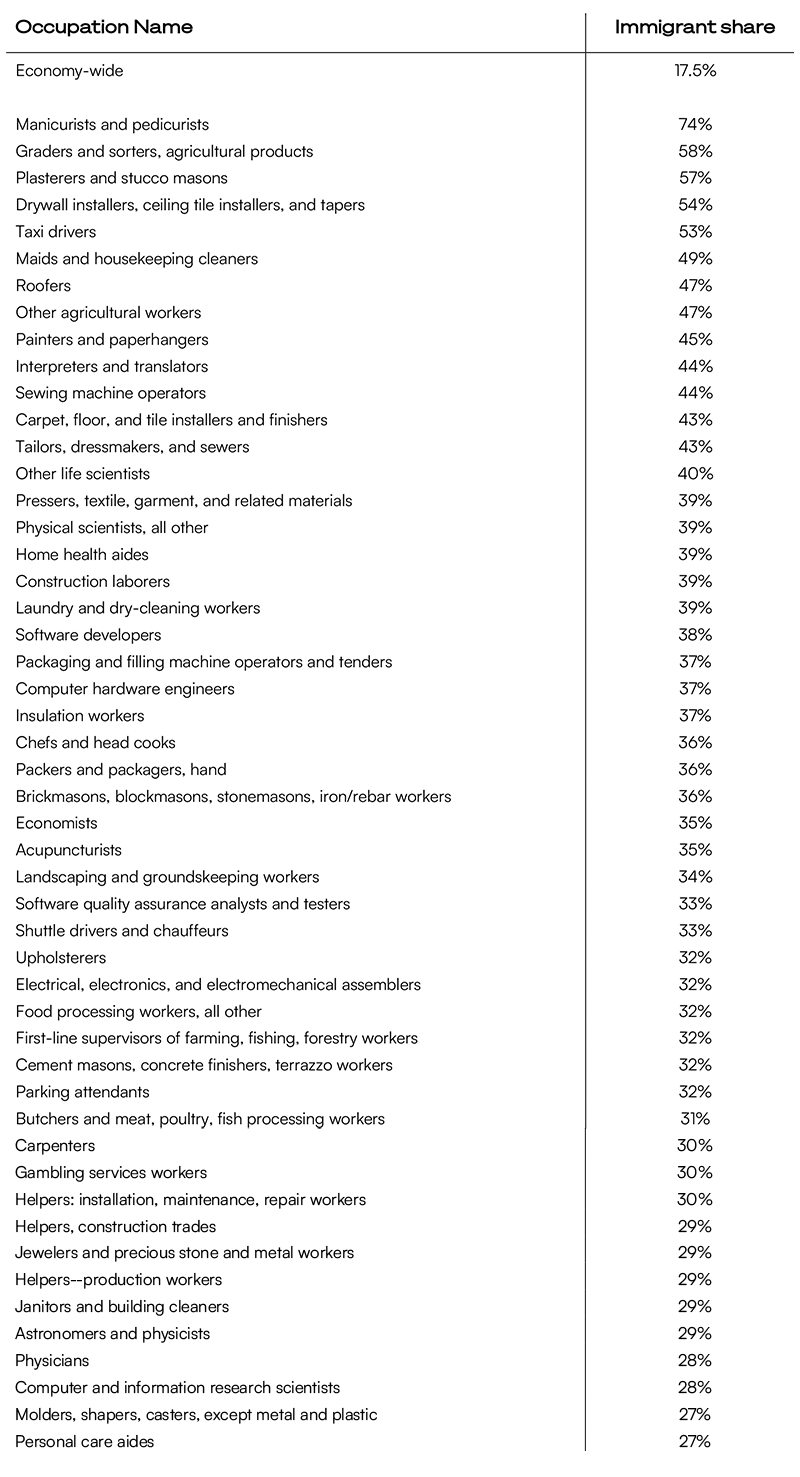

Within the sectors identified above, there are several occupations that are extremely reliant on immigrant labor. One can distinguish here generally between the blue-collar jobs that require a lot of manual tasks (“standing-up jobs”) and some high-skilled white-collar professions, which typically require many years of education (“sitting-down jobs”).

The manual jobs with a high immigrant share include construction workers and trades, drivers, food processing, hospitality jobs, personal care jobs, maids and housekeeping, janitors, cleaners and landscapers. Many of these standing-up jobs have a foreign-born worker share of 30% or above, some of them even exceed 50%.

Sitting-down jobs with a large immigration share include software developers, computer and hardware engineers, analysts and economists, astronomers, physicists, other scientists, and medical doctors. The foreign-born worker share is somewhat lower than for some of the manual occupations but still ranges from about 30% to 40%.

The table below displays the top 50 occupations in the U.S. with the highest migration share.

What stands out is that every single occupation in the top 20, other than software developers, is part of the standing-up jobs category. We know from research done by Pew that the share of undocumented workers is also relatively high: An estimated 26% of farming jobs and 15% of construction jobs.

It is precisely for these job categories that we should expect the biggest impact from Trump’s immigration policies. Many of the standing-up jobs will experience significant worker shortages more immediately before the impact spreads across the entire labor market. Workers employed in these occupations will also see larger wage gains more quickly.

Wage gains are on the table

We would be amiss if we didn’t point out some of the distributional consequences of more restrictive migration policies. As we pointed out in an earlier piece, lower migration creates a lot of losers due to a slower-growing economy. More rapid wage growth leads to more monetary tightening, which will create an additional economic drag.

However, there will also be a few winners first. Workers employed in labor shortage occupations will initially experience faster wage growth relative to the rest of the market. Eventually, higher earnings will attract workers from other industries though, thus mitigating wage pressures and worker shortages in these occupations, but creating more overall tightness across the entire labor market. With that in mind, Fed policy will aim to weaken the economy to contain inflationary pressures created by the tight labor market.

Technology can mitigate wage gains and production losses that arise from worker shortages

One big unknown when it comes to immigration restrictions is the potential of automation and technology to offset a big share of the negative effects. It’s worth recalling that the termination of the “Bracero program” in the 1960s, which ended the annual influx of hundreds of thousands of seasonal agricultural workers from Mexico, only had a minimal impact on the U.S. labor market. The reason is that farmers in Southern states adapted very quickly to changing circumstances. Productivity growth in agriculture was extremely high at the time. Farm owners introduced more capital-intensive modes of production and switched to crops that require less labor. Automation therefore mitigated the impact of worker shortages.

We might want to be careful though to rely too much on this historical analogy. Back then, only agriculture was affected whereas deportations today are affecting many different sectors across the entire labor market.

Nevertheless, both research and real-life examples show that automation potential might be relatively high across many different occupations. Fast-food restaurants and supermarkets increasingly rely on self-service checkout counters. Cleaning robots can easily replace many janitorial tasks. Self-driving cars can replace taxi and Uber drivers as well as truck drivers. 3D-printing can be used to solve worker shortages in construction. And robots are increasingly getting better at harvesting fruits and other crops.

Several studies have pointed out that non-college-educed immigration and robot adoption are substitutes. A study of the Danish labor market shows that large migration inflows inhibit robot adoption. Some economic historians have even suggested that high wages caused by labor shortages following the plague led to more automation and technological change, which helped spark the Industrial Revolution.

In part two of our series, we used an economic growth model to simulate the impacts of the upcoming non-college-educated worker shortage on the economy and labor market. While we found relatively strong GDP declines associated with a large drop in the workforce, the model also shows that a drop in GDP can basically be prevented with a higher rate of capital accumulation or faster technological change.

What is interesting is that we are not necessarily talking about outlandish growth rates. A 2% annual increase in the capital stock, or alternatively a 0.4% increase in productivity, is required to offset the decline in the workforce and keep economy-wide production constant. In that case, the negative GDP effects of restrictive migration policies are much smaller than what is commonly assumed.

While not our baseline scenario, it’s plausible that a sharp decline in non-college-educated labor can be almost completely offset by increased automation and capital investment. As labor shortages drive up costs, employers have an incentive to shift toward more capital-intensive production. However, these adjustments take time, think years, not months. In the meantime, restrictive immigration policies are likely to produce a significantly tighter labor market, leading to all the economic strains we have discussed.

Conclusion

The impact of the new immigration policies on different industries and occupations will vary. Many jobs in agriculture and construction will be especially labor strapped because they are very reliant on the immigrant workforce.

But some of the roles can be automated. Companies are likely to respond to surging wages of non-college-educated workers by replacing some workers with machines, which could have some potential positive spillovers to the economy overall. However, automation potential will be limited in the short-term for many of the standing-up jobs like construction and maintenance trades, agricultural work, housekeeping, elder care, and hospitality.

While the U.S. economy and labor market will survive Trump’s deportation policies, though maybe with some ruffled feathers, many businesses that are active in one of the above industries might not. Staffing needs might change overnight, and recruitment costs are likely to surge.