Predicting recessions is futile

If forecasters have learned anything from the last two years, it should be that predicting recessions is a fool’s game. More specifically, from a macroeconomic standpoint, forecasting future economic downturns doesn’t even make sense!

Economists are struggling to estimate GDP in real-time (figures are usually released about a month after the quarter has already ended). Not only that, but GDP figures are often subject to large revisions.

Furthermore, it is the aim of central banks to stabilize the demand side of the economy. If recessions were easy to predict, policy makers would simply be able to prevent them. Recessions in advanced economies usually stem from policy mistakes!

While policy makers cannot easily offset supply shocks – surging food and commodity prices, wars, etc.– they are inherently unpredictable. Therefore, it usually does not make sense to forecast negative growth well in advance.

The odds of soft landing are rising

However, none of these objections prevent forecasters from forecasting, especially in recent years. The first recession calls for 2023 were issued in mid-2022 when U.S. GDP figures first showed a temporary dip. Bloomberg confidently assured us back then that a recession would occur within a year with a 100% probability. Since growth has now far exceeded expectations, they shifted their recession call to 2024. And they are not alone.

I guess the motto is: “When you’re wrong, double down, and then double down again.”

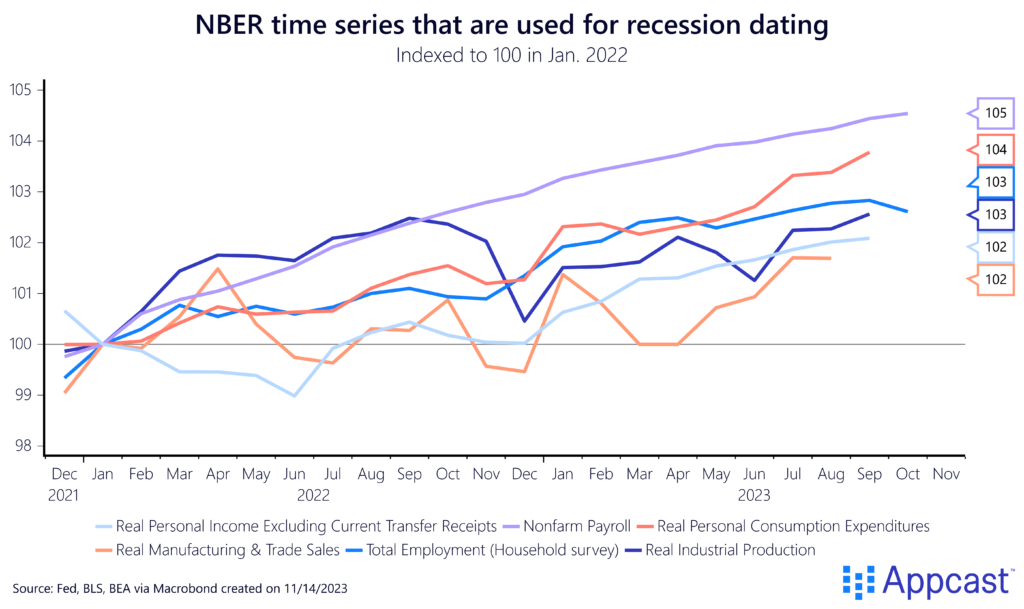

How exactly is a recession determined, if it’s not by forecasters’ insistence? The NBER business cycle committee uses six different economic measures to determine whether or not the U.S. economy is in a recession: Nonfarm payrolls, employment growth, real personal income, real personal consumption expenditures, real manufacturing and trade sales, and real industrial production.

There was no reason to believe that the U.S. economy was in a recession by mid-2022 based on the NBER indicators, despite the fact that GDP figures recorded two quarters of decline (Gross Domestic Income, an alternative measure for GDP, was still growing at the time).

Predictions of an imminent downturn for early 2024 will likely not pan out either. The Atlanta Fed Nowcast model forecasted a high GDP growth rate for Q3 and was right on the money. And even Q4 is expected to come in at a very respectable two percent.

So why did high rates not cause a crash?

To be fair, forecasters were reacting to a marked reversal in macroeconomic conditions – the interest rate outlook quickly shifted in response to inflation.

Interest rates had been very low globally before the pandemic to stimulate growth after the financial crisis. If policymakers had risen rates, there is little doubt a substantial economic downturn would have followed.

Economists have estimated that the natural rate – the inflation-adjusted interest rate that is consistent with stable growth – was near zero. With two percent inflation, that means that nominal interest rates should also be around two percent, which is basically where the Fed’s policy rate was back in 2019.

Economic models are now telling us that this natural rate has surged following COVID-19. And this means that the Fed can and must raise interest rates to a higher level during this economic cycle to tame inflation and bring the economy back to trend.

They are doing this because economic booms, just like busts, are undesirable in their instability – policy makers aim for stable growth.

But this begs the question, why did this natural rate increase so much? What are the factors have made the economy so much more resilient to interest rate increases?

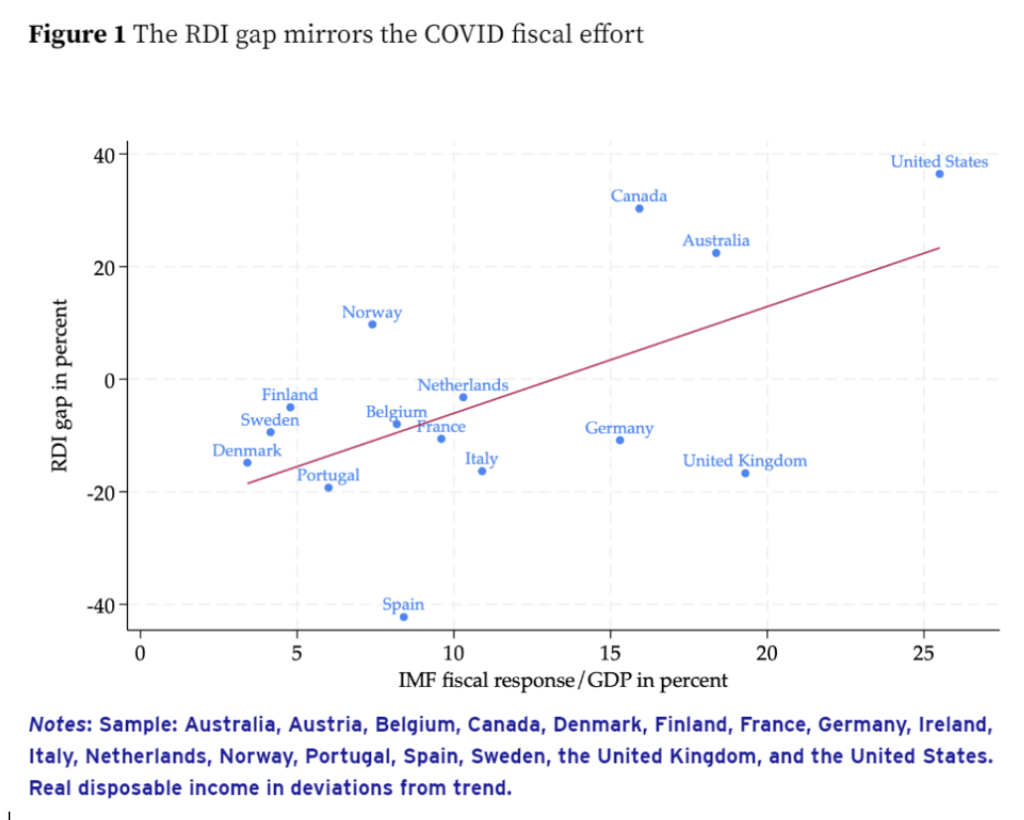

1. Fiscal support massively boosted incomes

A recent study explores the relationship between the size of the COVID fiscal stimulus and subsequent growth in real household disposable income compared to trend. As the following chart shows, the U.S. has been a clear outlier amongst advanced economies. The size of the U.S. COVID response equalled some 25% of GDP. The very generous stimulus checks that were sent out contributed to the massive surge of household income in the U.S., shared across all layers of society.

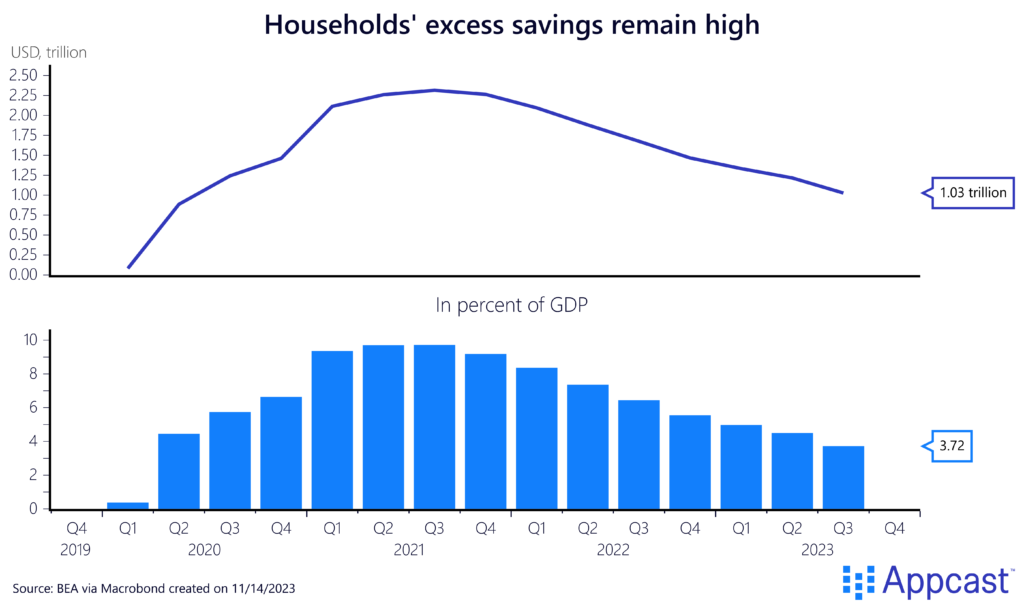

2. Excess savings supported spending

With the intermittent shutdowns of the economy during COVID, consumers were unable to consume as many services as they would normally have had. Excess savings measures to what extent savings surged above trend during that period. This measure peaked at about 9% of GDP in 2021, some $2.3 trillion. According to this measure, there might be still some $1 trillion left in savings, which still supports consumption spending in the U.S.

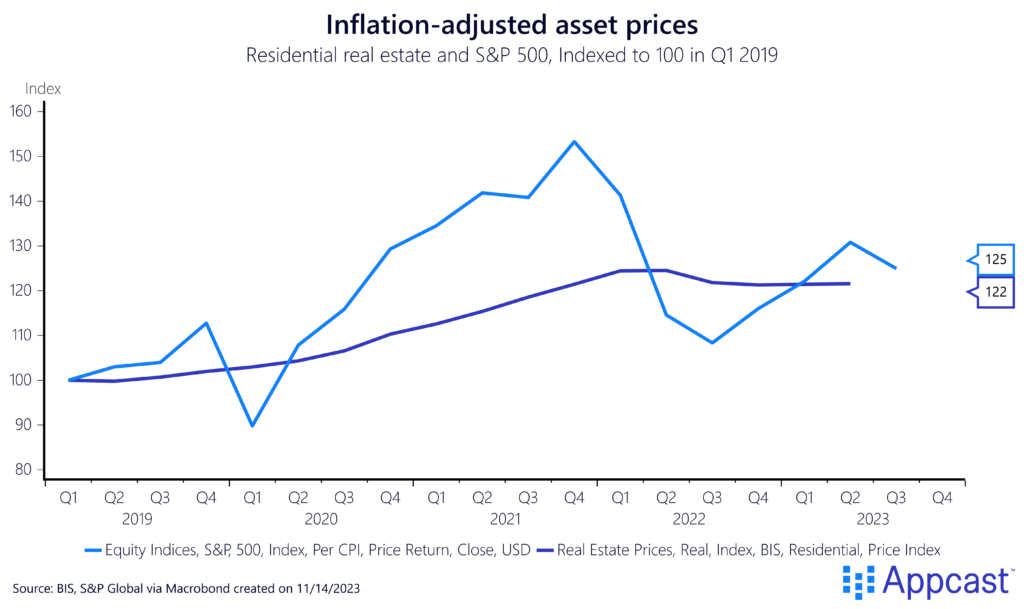

3. Asset prices surged, creating a positive wealth effect

Asset prices have surged since the pandemic, also thanks to the very generous fiscal and monetary support. House and stock prices are more than 20% higher than in 2019 – even adjusted for inflation! As we reported recently, Fed data shows that Americans are more prosperous than ever. Net worth has gone up across all income groups, which is supporting the economy.

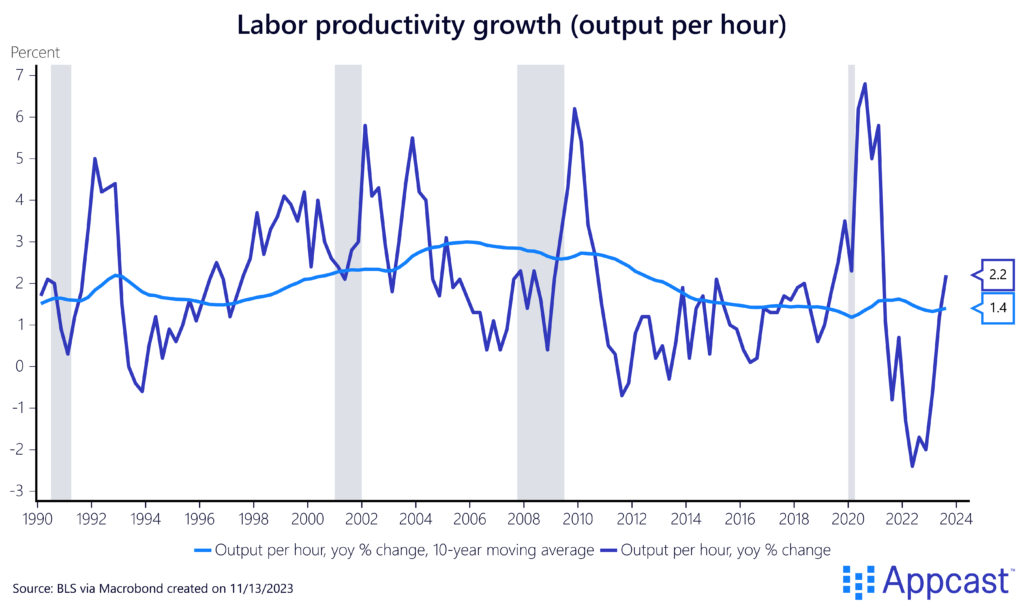

4. Productivity growth accelerated

Productivity has been extremely low in recent decades. It surges temporarily during downturns because low-productivity sectors are affected the most and low-productivity workers tend to be laid off first. The productivity dip in 2022 was followed by very strong growth in recent quarters, which is providing a significant boost to the economy this year.

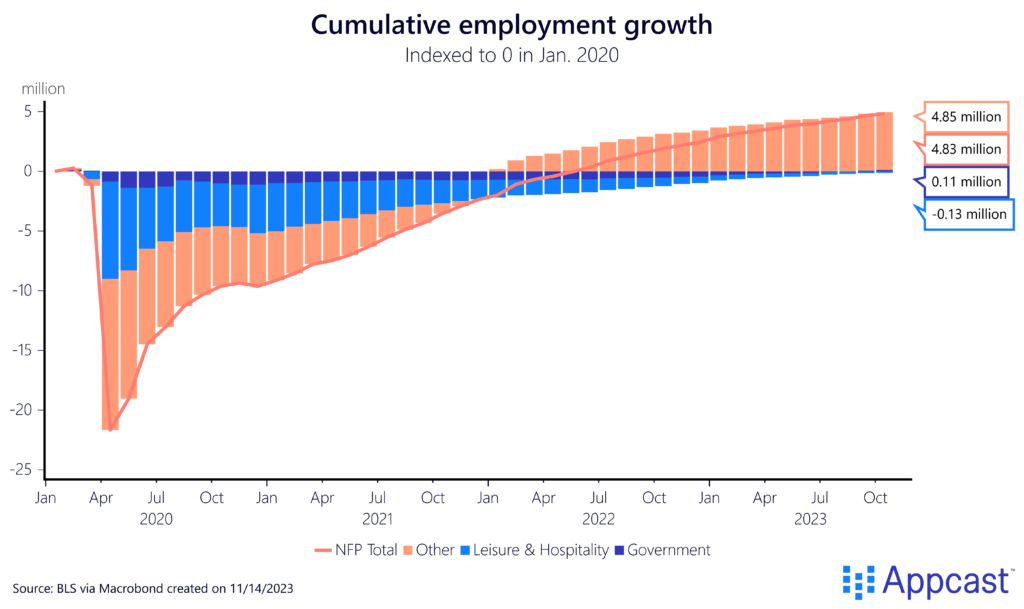

5. The strong labor market is maintaining current spending

The U.S. economy is currently enjoying one of the longest spells of below-4% unemployment. The labor market recovered extremely swiftly from the COVID shock. Not only have all the jobs been regained, but employment is now close to 5 million higher than before the pandemic. With the U.S. labor market being at full employment, household spending is being financed out of current income. There isn’t even any need for excess savings or surging asset prices. They are just a bonus.

6. Most importantly, nominal income growth is way above trend

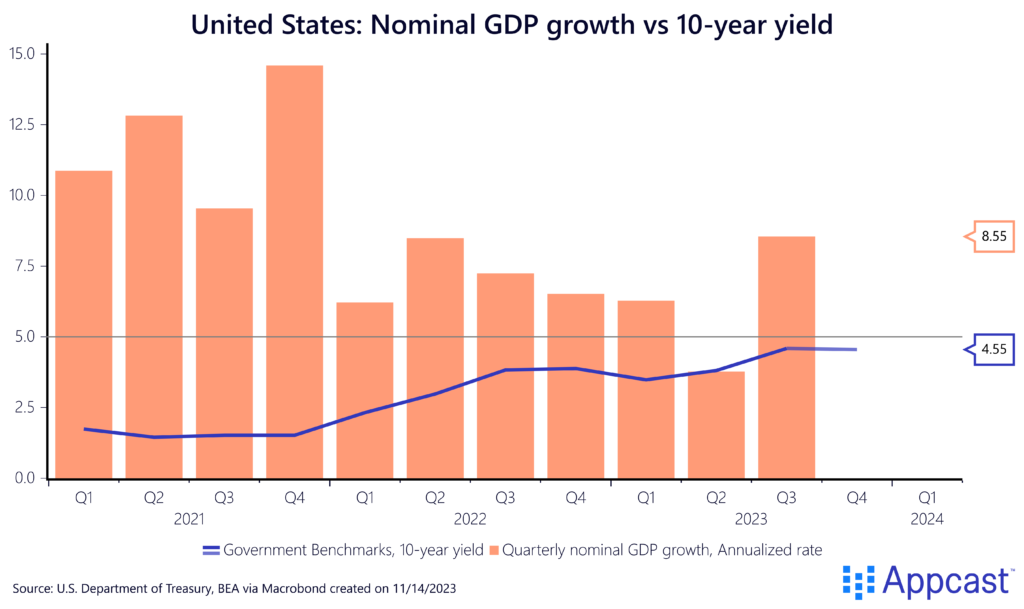

Interest rates are not a good measure for the stance of monetary policy (neither real nor nominal). Former Fed chair Ben Bernanke has emphasized that nominal GDP growth is the only reliable indicator for whether money is tight or loose.

While interest rates have risen a lot since 2020, nominal GDP growth has been growing at annualized rate of more than 8% recently. High interest rates are not contractionary and won’t hurt the economy when nominal incomes are growing at such a fast pace. The one thing that could really hurt the economy is a substantial nominal GDP slowdown, but nominal incomes continue to run above trend, which ultimately means that monetary policy is not tight at all.

Conclusion

Many forecasters incorrectly assumed that high rates would plunge the U.S. economy into a recession in 2023. As this has not happened, the goalpost just shifted to next year. But as I outlined above, there several reasons to be skeptical about this forecast. The so-called neutral rate is currently much higher than before the pandemic, which means that monetary policy is not tight. Absent a large and abrupt slowdown in nominal GDP, expect a growing U.S. economy and full employment in 2024.