First Japan…

Nobel prize winner Paul Krugman was right when he suggested more than a decade ago that the Japanese economy would be a precursor of things to come. The country was the first to struggle with zero-interest rates after its massive stock and real estate bubble deflated in the early 1990s. The Bank of Japan also was the first to implement large-scale Quantitative Easing (Q.E.) programs, buying government bonds with newly created central bank money to combat deflation. However, similar to the Fed’s and ECB’s efforts a decade later, Q.E. was of little effectiveness. Most importantly, Japan has struggled with adverse demographics already for decades. Here again, the country has led most of Europe by about a decade or so.

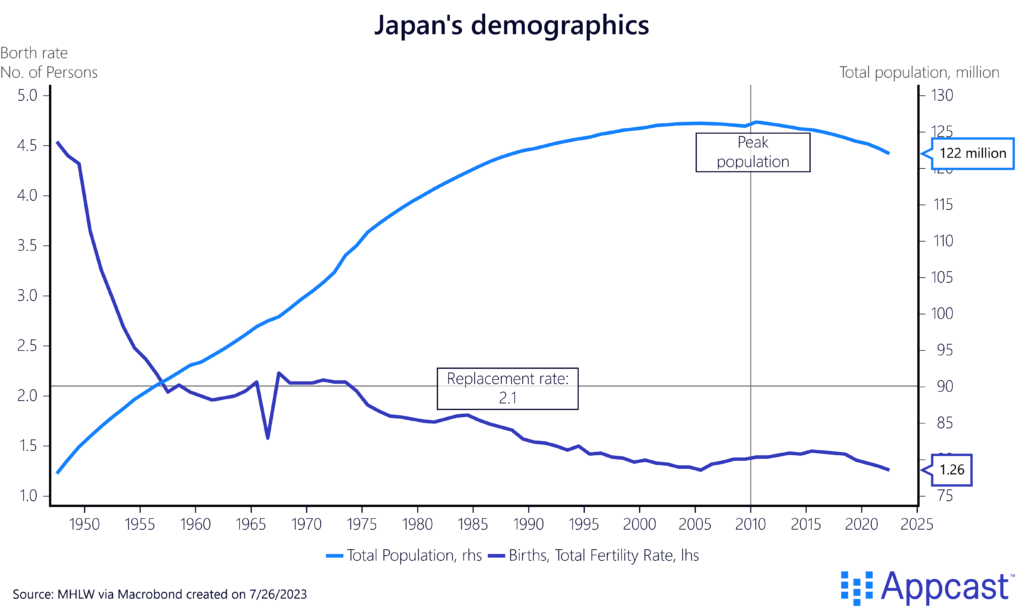

Japan’s fertility rate fell below 2.1 in the mid-1970s and has steadily declined afterwards to a low of about 1.3 in recent years. As a result, Japan’s population peaked in the late 2000s and has shrank ever since.

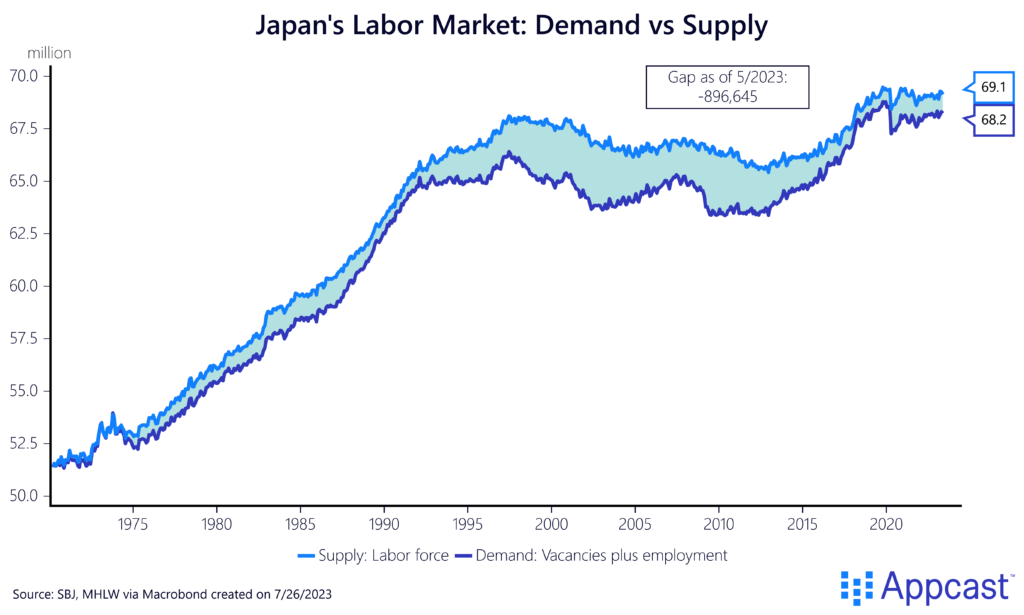

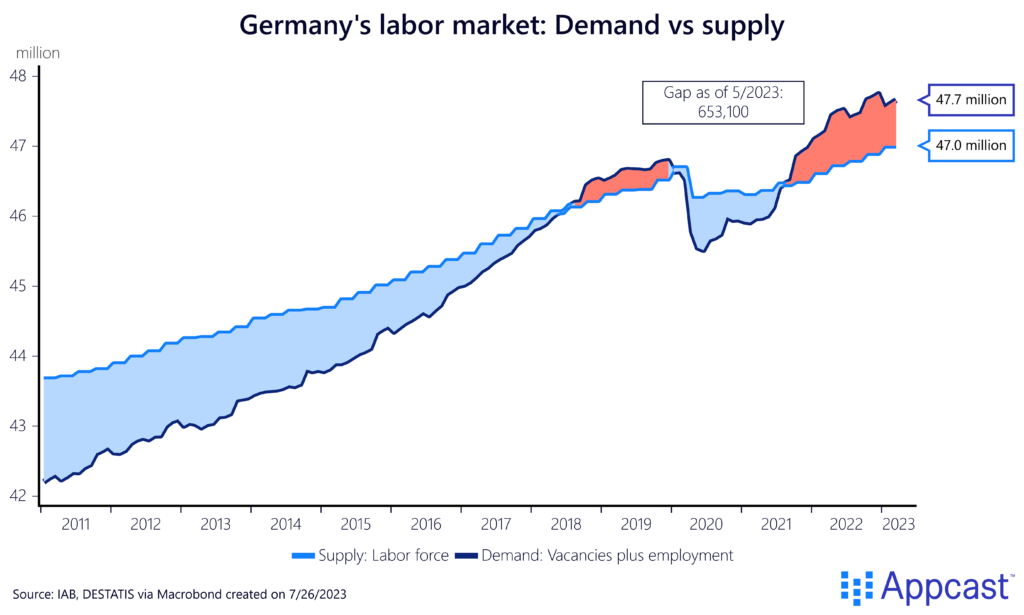

The following chart shows how the gap between the total demand for labor, vacancies plus employment, is now closer than ever to the total supply, the available workforce in the economy.

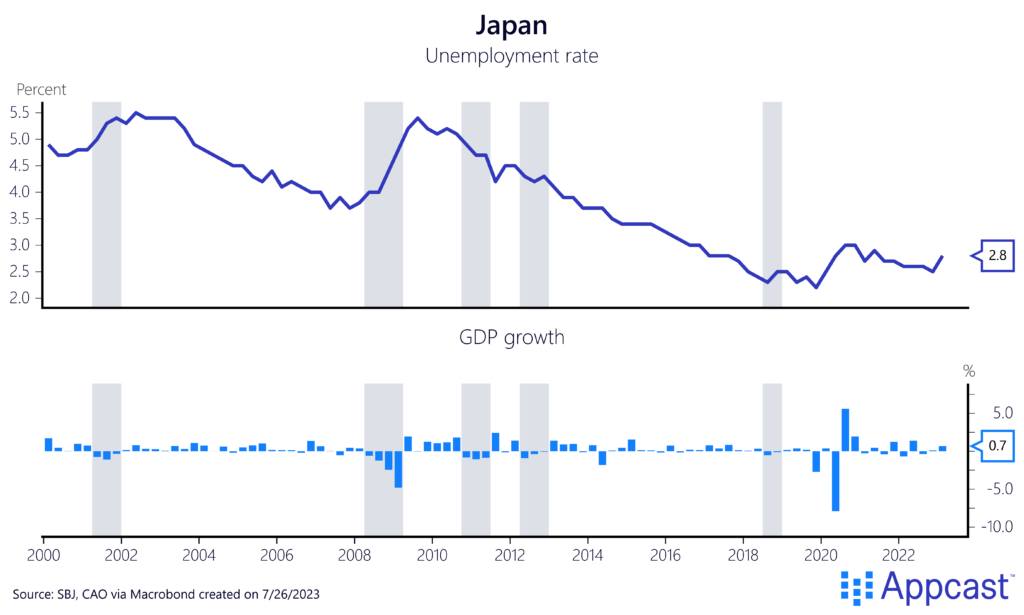

With a rapidly shrinking labor force and declining population, trend GDP growth has substantially declined over time. Moreover, productivity gains have also been disappointing since the late 1990s, putting further downward pressure on growth rates.

As a result, Japan has experienced several technical recessions in recent years – defined as two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth.

Both adverse demographics and mediocre productivity growth can explain why rapidly aging economies like Japan will see more and more technical recessions in the future even as the labor market remains strong. One can see how Japan’s unemployment rate continued to decrease even as economic growth sputtered, simply because the country’s labor force has shrank and workers have become scarcer. Japan is in the midst of a full-employment recession.

…Now Germany and Europe

The long-run demographic outlook for many European countries is extremely similar – following Japan with a small lag – since fertility rates have declined for decades and have fallen well-below the replacement level of 2.1. It should thus be no surprise that labor shortages will increase in severity in the coming years. Our own research shows that Germany alone is missing some 650,000 workers right now, if not more. And this gap is only going to increase as the country’s population is aging rapidly.

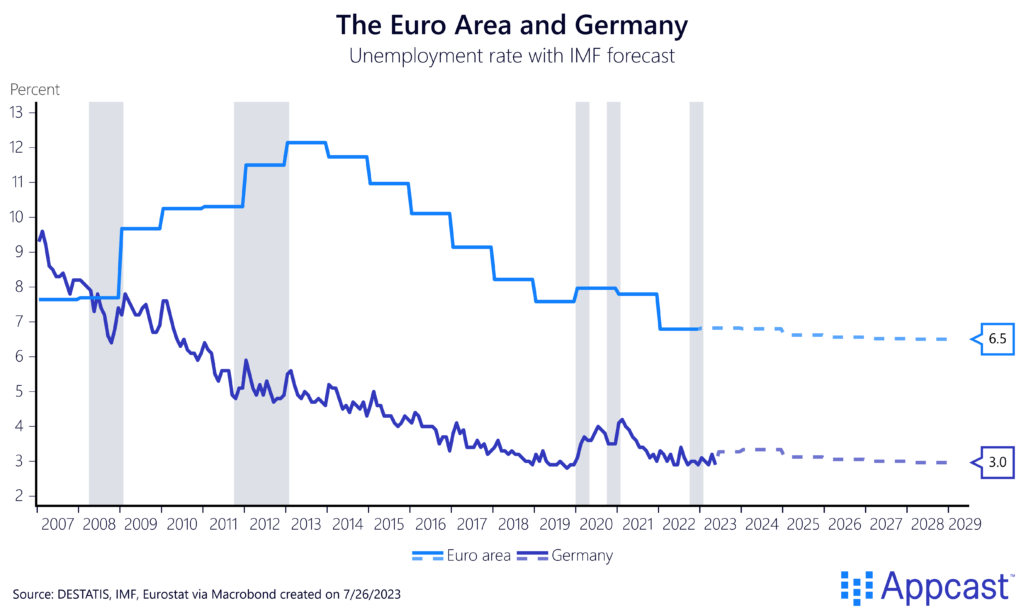

Even as Germany has now fallen into a technical recession – and the Eurozone only narrowly avoided one – unemployment rates have continued to decline. And IMF forecasts suggest that they will remain lower for the foreseeable future than they have been in the past. Companies scarred by the recruitment difficulties in 2021 and 2022 will predominantly engage in labor-hoarding first before letting people go. So do not expect the current labor market tightness in the Eurozone to ease up any time soon!

In the coming decades, Eurozone economies will experience more technical recessions because the shrinking population is weighing on growth. At the same time, unemployment rates will remain at record-lows as labor shortages intensify. And as long as the labor market remains tight, we really should not care about occasional declines in GDP growth, especially if per capita income continues to increase.

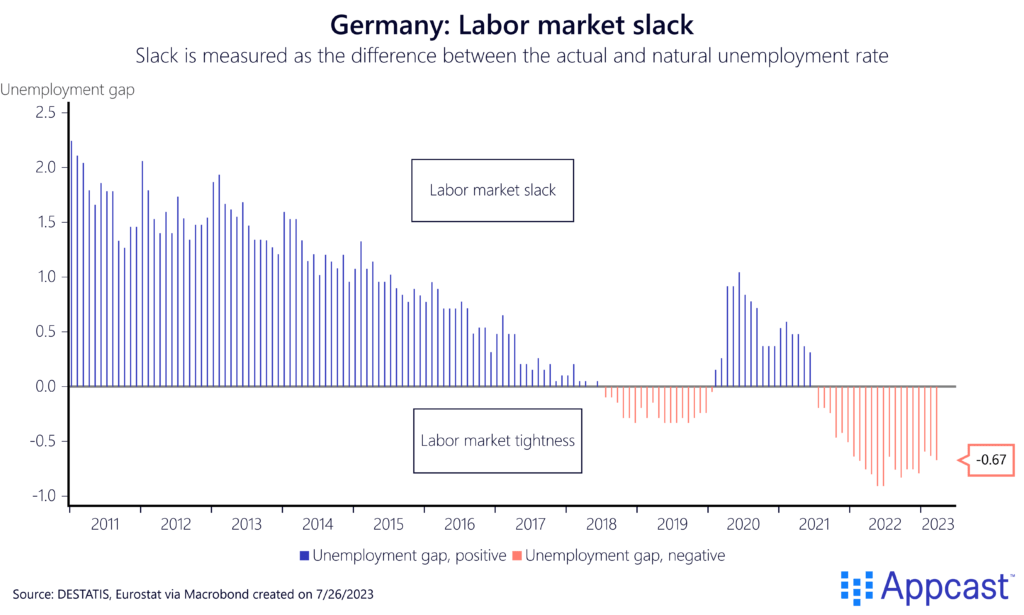

A recent paper by Michaillat and Saez estimates the natural rate of unemployment – the unemployment rate that is consistent with price stability and the economy being close to full employment – for the U.S. economy.

We use the same methodology to get an estimate for the natural rate of unemployment for Germany. What our chart shows is that labor market slack gradually softened over time during the 2010s. By 2018, Germany’s labor market was already tight as the actual unemployment rate fell below the estimated natural rate for the very first time. And this labor market tightness has only increased with the pandemic and will remain for the foreseeable future, given that Germany’s working-age population has already started to decline.

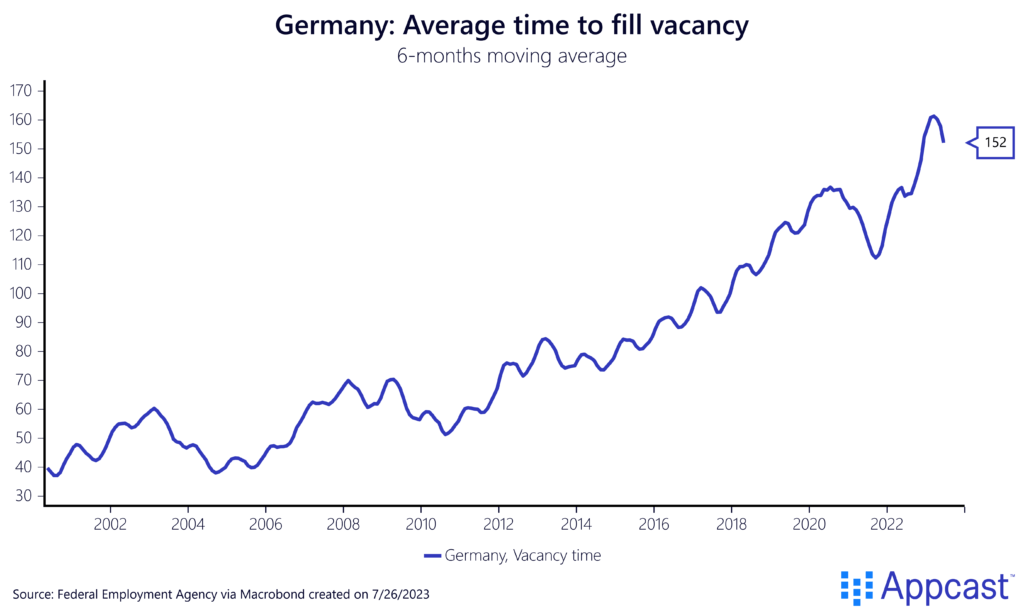

Not only are labor shortages limiting production more and more at German companies across all sectors, they are also leading to elevated recruitment costs. The average time to fill a vacancy has tripled from about 50 days in the mid-2000s to more than 150 days recently. The costs to employers of vacancies being unfilled has surged in recent years.

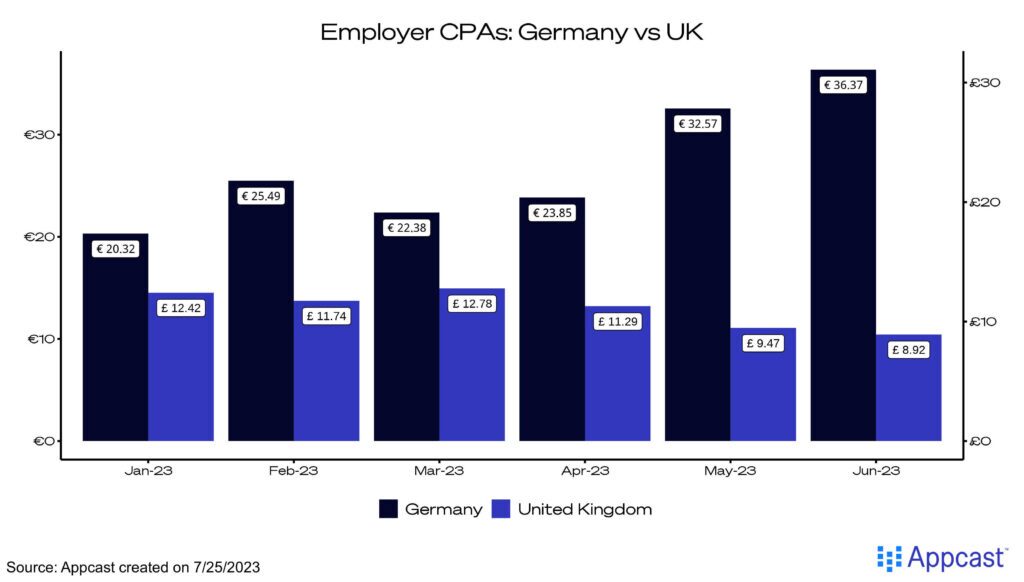

Appcast’s own data suggests that the cost-per-application (CPA) in Germany is substantially higher than in the U.K., for example. CPAs reflect demand and supply conditions in the labor market. A high CPA is indicative of a shortage of workers for open positions. Recruiters in Germany are willing to pay substantially more for each application they receive.

Conclusion

Demographic developments in Europe, and in Germany in particular, have produced extremely tight labor markets. It is estimated that Germany will soon miss several million workers unless the recent surge in migration provide can be maintained and provide some relief.

With a shrinking workforce over time, technical recessions will become more likely in a low productivity environment. These developments mean that, similar to Japan, Germany will experience more full-employment recessions in the future unless productivity growth significantly accelerates. While the recent advances in AI are spectacular, they will only start to have an effect on economy-wide productivity with a substantial lag, just as it took time for past technologies to significantly alter and transform the economy.